|

Social Science Time Line

Social Science Time Line

Mental Health History Time Line

Mental Health History Time Line

America Time Line

America Time Line

|

|

CrimtimA criminology and deviancy theory history timelinebased on The New Criminology. For a social theory of deviance (1973), by Ian Taylor, Paul Walton and Jock Young and Rehabilitating and Resettling Offenders in the Community (2012) by Tony Goodman. |

Roman Republic "During the time of the republic, freemen were never put to the torture, and slaves only were exposed to this punishment"

From 1154: a common law for England

1166 The Assize of Clarendon, a law of Henry 2nd, established

courts throughout the country, and

prisons for those awaiting trial. Each

shire (county) was required to provide a gaol where people could be

detained until the court appearance or punishment. The gaol was not

considered a form of punishment.

(See

below)

Prison was not,

in itself, generally considered as

punishment

(See above). However, there are some statutory provisions for

imprisonment as punishment. These include a year sentence and fine for

poaching in the royal forests. From the

12th century on, their was an increase in the number of prisons

In England, and also an increase in their use as punishment for crimes such

as fraud

and for petty crime, and sometimes even felonies.

(Norman Johnston

2009 p. 11S),

Felonies and the death penalty "Next below treason stand the

felonies. Common law felonies

... consist of those crimes that have been considered as peculiarly grave

at the time when our

common law first took shape in the thirteenth century: homicide,

arson, burglary, robbery, rape and larcency. Broadly speaking we may say

that they were capital crimes, save petty larceny, stealing to less value

than 12d.

(Maitland, F.W. 1963 p.229)

Gruesome Displays

Humiliation punishments 1351 Following the

Black Death, the English

Statute of Labourers of 1351 required that "stocks be made in

every town" and that twice a year farm labourere be required to take an

oath to work for the established wage in their usual place of work. "those

which refuse to take such oath or to perform that that they be sworn to

... shall be put in the stocks... by three days or more, or sent to the

next gaol, there to remain, till they will justify themselves."

text of Act - Pillory

1562/1563 -

Deborah Wilson

1669

1362/1378

Wikipeda claims that "There is a reference

from about

1378 to a

cucking-stool as wyuen pine ("women's

punishment") in

Langland's Piers Plowman, B.V.29."

I am not sure that is what the

passage (below) means:

1401

English Act for the burning of

heretics

1422 to 1461

Henry 6th King of England

1487 Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of the Witches) published in

Germany - See England an Scotland 1562/1563 - King James 1597 - Pendle 1612 - Bideford 1682 - Salem 1692.

About

1500

Eight capital crimes were defined: treason,

petty treason,

murder, robbery, larceny, rape and arson.

(Timeline of capital punishment in Britain

(archive)

-

which does not say what the eighth was)

1533 An Act for the punishment of the vice of Buggery (25

Henry 8 c. 6) made anal intercourse (sodomy) with a man, woman or animal a

civil, rather than ecclesatical crime, with the penalty of hanging.

November 1554. English heresy laws, which had been repealed, were

reinstated. Under them, convicted

heretics

were to be burnt alive. The burnings began in February 1555.

1562 or 1563 English

Witchcraft Act. If the witchcraft was held to

have caused someone's death, the witch shall "suffer pains of

death as a

felon" (that is, be hanged). if it caused injury to someone's

person or goods, the witch was to be detained in prison for a year and

"once in every Quarter of the said year", on a market day or fair "stand

openly upon the Pillory" for six hours and "there shall openly confess his

or her "error and offence". For a second offence, the witch would be hung.

27.5.1610

Francois Ravaillac executed in Paris by being pulled apart by

four horses. See

types of punishment

11.4.1612 Edward Wightman was executed by being burnt alive in the

Market Place at Lichfield. His crime was

heresy. Wightman is believed to be the last person in England to

be

executed for heresy by burning alive

Summer 1612 Pendle (Lancashire)

witch trials convicted convicted the accused on the evidence of

a child.

Transportation of convicts "Between 1614 and

1775 some 50,000 English men, women, and children were

sentenced... to be sent to the American colonies for a variety of crimes".

See

National Archives Guide

1640

Abolition of the Star Chamber in England meant the abolition of

any torture allowed by English law.

See 1585 -

1666 -

1672 -

1673 -

1780 -

1782 -

1789 -

1813 -

1817 -

1827 -

1903

1215 "Brawling women undergo the punishment of the 'Coking

Stole'"

Cornwall quotation in Oxford English Dictionary, which describes the

cucking, cukkyng, cuckyng, cooking or cuk stool as "An instrument of

punishment formerly in use for scolds, disorderly women, fraudulent

tradespeople, etc., consisting of a chair (sometimes in the form of a

close-stool), in which the offender was fastened and exposed to the jeers

of the bystanders, or conveyed to a pond or river and ducked." See 1362/1378 and

1511

By the English

Treason Act of 1351, the punishment of men

was to be hung, drawn and quartered and the punishment of women was to be

burnt. See also burning of

heretics. France, see Foucault on the

Ordinance of 1670.

"Tomme Stowue he taughte to take two staves

And fecche Felice horn fro wyve pyne."

1563 Scottish

Witchcraft Act

|

John Bunyan

1678 John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (Part One) in which Christian follows the straight and narrow path to heaven (external link to text) 1680 John Bunyan's The Life and Death of Mr Badman outlines his staggering steps to hell (external link to text) 1684 John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (Part Two) In which Christiana follows her husband, Christian, with her children

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the works of Bunyan and the

Bible were amongst the very small range of books that one might expect to

find in the homes of ordinary, but literate, people in England and Wales.

They shaped the common perception of crime and punishment.

|

|

France:

Ordonnance criminelle de 1670

Enacted under the reign of Louis 14th Made in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Registered by the Parliament of Paris (a court) on 26.8.1670. Came into effect on 1.1.1671 "one of the first legal texts attempting to codify criminal law in France."

See

Foucault

Remained in force until the French Revolution. Abrogated (repealed) by a decree of the National Constituent Assembly on 9.10.1789.

Main source:

Wikipedia

Torture to extract confessions or to extract the names of accomplices was permitted under some circumstances under the code. Torture to extract confessions was abolished in 1780. Torture to extract the names of accomplices was abolished in 1788 |

1673 The "Old Bailey" court rebuilt

1674 "News from Newgate: or an exact and true accompt of the most

remarkable tryals of several notorious malefactors... in the Old Baily".

The first of the publications reproduced as:

"The Proceedings of the Old Bailey 1674-1913" online.

"Punishments at the Old Bailey - Late 17th Century to the early 20th Century" outlines the evolution of punishment.

May 1717 France: Voltaire imprisoned in the

Bastille for eleven months, accused of writing two anonymous libels.

See Salem Witch

Trials

"This was a turning point for Voltaire, for he felt the sting

of injustice most keenly, and it surely influenced his later campaigning

against the injustices dealt out to others."

(source)

In 1725

Voltaire was imprisoned for a second time in the Bastille

and later exiled to England. See

1762 -

1763 -

1764 -

1722 Sweden the first Continental European state to abolish torture.

1754 Prussia the second Continental European state to abolish

torture.

|

5.1.1757 France: Robert-François Damiens, an unemployed domestic servant, rushed at King Louise 15th of France, stabbing him with a knife and inflicting a slight wound. Damiens was condemned ( 1.3.1757) as a regicide (a person who kills a king) and sentenced to be publicly drawn and quartered, by horses. The execution was carried out on 28.3.1757 - See Foucault and Wikipedia

France: From the

1760s A campaign to reorganizing the justice system in

which the writings of

Voltaire were influential.

10.3.1762 Execution of Jean Calas in Toulous haveing been "condemned

to the

torture, ordinary and extraordinary, was then broken upon the

wheel,

and finally burnt". See

Catholic Encyclopedia 1913 -

Wikipedia -

Casper Hewett

1763

Traité sur la Tolérance … l'occasion de la mort de Jean

Calas by

Voltaire

| The Language of Law Beccaria, in 1764, speaks of the laws "being written in a language unknown to the people" in "the greatest part of our polished and enlightened Europe". By this, I believe he refers to the Holy Roman Empire, of which the part of Italy where he lived was part. See 1784 |

|

Classical Criminology

Italy: Cesare Beccaria's Dei delitti e delle pene published in Italian. It was translated into French, and from the French into English as An Essay on Crimes and Punishment (1767) with a commentary attributed to Voltaire. Beccaria's Essay on Crimes and Punishment is taken as the first formulation of the principles of classical criminology. It is called classical because the later "positivist school of criminology" saw itself as a modern development that moved beyond the classical by being more "scientific" than "philosophic". Biological Positivism was established a hundred years later in the same area of Italy by Cesare Lombroso. Beccaria built on the idea of "social contract" used by state of nature theorists such as Hobbes and (later) Rousseau, and on theories later called utilitarian (Helvetius and David Hume). This is how Taylor, Walton and Young (1973 page 2) claim classical theory can be summarised in seven points. Jennifer Seelig has identified parts of Beccaria's Essay on Crimes and Punishment that may illustrate six of the points. I have linked through to these.

1) Everyone is, by nature, self-seeking and this means everyone is

liable

to commit crime.

Compare

Beccaria 2.3

2) There is a consensus in society that it is desirable to protect

private

property and personal welfare

Compare

Beccaria 3.2

3) In order to prevent a

war of all against all, people freely enter

into a contract with the state to preserve the peace within the terms of

this consensus.

Compare

Beccaria 2.5

4) Punishment must be used to deter individuals from violating the

interests of others. It is the prerogative [monopoly? -

see Weber] of the state, granted to it by the individuals making

up the social contract, to act against these violations.

Compare

Beccaria 41.2 and

Beccaria 12.2

5) Punishments must be proportional to the interests violated by the

crime.

It must not be in excess of this, neither must it be used for reformation;

for this would be encroach on the rights of the individual and transgress

the social contract. [This is a contentious aspect of the Taylor, Walton,

Young summary - But they do not back it up]

Compare

Beccaria 47.3

6) There should be as little law as possible, and its implementation should be closely delineated by due process 7) The individual is responsible for his actions and is equal, no matter what his rank, in the eyes of the law. Mitigating circumstances or excesses are therefore inadmissible. Compare

Beccaria 21

Quite what this summary summarises is not entirely clear, but Taylor,

Walton and Young indicate their broad concept of classical theory when they

speak of "classical social contract theory - or utilitarianism". - The

utilitarian Bentham considered social contract theory "nonsense upon

stilts" - The Taylor, Walton and Young list appears to be a construct

taking elements from different eighteenth and early nineteenth century

theories, and possibly combining them with elements from 20th century

theories. It's educational value must include trying to find theorists who

agree or disagree with its elements.

|

|

1770 Denmark abolished torture. Russia abolished torture in

1774

Norman Johnston

(2009) describes it as the "first large-scale adult penal

institution to use architecture to implement a reform-minded penal

philosophy. When four of the

eight trapezoidal sections were completed in 1773, they separately

housed

male felons, beggars, women, and unemployed labourers and abandoned

children-a very early example of classification of different types of

inmates. Ghent remained a model prison until it later became seriously

overcrowded-always a spoiler in the history of prison reforms"

1776

Abolition of torture in the Austrian empire, of which

Beccaria's Milan was part.

|

Bentham's Utilitarianism

Britain Jeremy Bentham's A Fragment of Government published Criticising Blackstone's conservative theory. In 1768, Bentham had decided to provide a scientific foundation for jurisprudence (the science of law) and legislation (laws passed by parliament). He formulated the principle of utility, that the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the only proper measure of right and wrong and the only proper end of government. His early manuscripts frequently mention Helvetius and Beccaria

See Panopticon

Beccaria wrote "That a punishment may produce the effect required, it is sufficient that the evil it occasions should exceed the good expected from the crime"

Bentham and Crime and Punishment Bentham's theories relate crime to learning more than to inborn propensities. His psychology is based on the association of ideas. Utilitarian theory: One needs a balance of pain and pleasure that will lead to people doing what is socially desirable:

See how this was applied to social security

See how this was applied to crime and punishment See how Foucault applies it to madness See this biographical literature review

|

Modern Prisons

| Prison as a mode of punishment and reform developed, in theory and practice, during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Foucault argues that the theory of discipline developed before the practice. |

Britain John Howard's The State of the Prisons

Germany

Immanuel

Kant's

philosophy is the major alternative to

Utilitarianism. Kant developed the

moral ideas of

Rousseau

into a formal theory of the difference between reasoning about what is

(science) and reasoning about what we ought to do (ethics, or "practical

reason"). His theories are a criticism of the Scottish utilitarian

philosopher, David

Hume.

24.8.1780 France: Royal Oridinance of Louise 16th abolished

the "preparatory question" (question préparatoire): the form of

torture that accused persons were forced to undergo in order to

extract

confessions from them.

1782

A new Newgate Prison finished

1783

Public hangings moved from Tyburn to Newgate. (See

1789

and 1817

| Germany Immanuel Kant's The Critique of Pure Reason |

|

Germany Immanuel Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

From 1785 to 1788, Jeremy Bentham travelled the Continent, including Russia. It was here that he developed his idea of a model institution: the "Panopticon". He developed the idea in a series of letters from Russia to a friend in England, in 1787. These were published in 1791

30.11.1786 Tuscany's reformed penal code officially abolished the

death penalty, ordered the destruction of the instruments of execution, and

banned torture.

Germany Immanuel Kant's

The Critique of

Practical Reason

1788 France: Royal Oridinance of Louise 16th abolished

the "preliminary question" (question préalable) - a form of

torture

designed to obtain from those who had been convicted the names of their

accomplices

1788 London: The Philanthropic Society started "over a cup

of coffee".

"The Philanthropic Society was the second children's charity to

be set up, following the Thomas Coram Foundation, but it was the first with

the aim of preventing children from committing crimes. At that time,

children could be sent to the gallows and many were sent to prison for

minor crimes. The Society opened homes to feed and care for the children

and also to train them in cottage industries such as printing, shoemaking

and twinespinning often going on to be apprenticed to local craftsmen."

(source)

|

The end of the eighteenth century saw the end of some

gruesome displays. Notable was the end of publicly

burning the (dead) body of

people convicted of

petty treason

(notably husband murder) and the end of

the public exhibition of lunatics at Bethlem Hospital.

[John Stuart Mill discuses petty treason in The Subjection of Women]

|

May 1789: Start of the French Revolution

"Let penalties be regulated and proportional to the offences, let the death sentence be passed only on those convicted of murder, and let tortures that revolt humanity be abolished"

|

1789

Britain Jeremy Bentham's An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation published

See

Surveillance -

Bentham on -

mental health

timeline -

social science

timeline -

Bentham and intervention -

asylum architecture -

panopticon and

radial -

Wakefield -

Narrenturm

- Prison architecture -

Millbank -

Pentonville -

Foucault on -

Workhouse

architecture -

1898: radical break from this design.

|

||||||

|

France:

Code pénal

du 25 septembre -6 octobre

1791 -

see dictionary

External link: The French Revolution and the organisation of justice John Lewis Gillin says that, following the French Revolution, Beccaria's principles were used as the basis for the French Code of 1791. Beccaria had said

"crimes are only to be measured by the injury done to society. ... They err ... who imagine that a crime is greater or less according to the intention of the person by whom it is committed." So the French code said exactly what the penalty for every crime should be. Individual circumstances were not taken into account. In practice, this caused problems and modifications were introduced. Gillin says that these modifications "are the essence of the so-called neoclassical school".

"In 1791, when Louis-Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau (1760- 1793) presented the newly drafted criminal code to the National Constituent Assembly, he explained that it outlawed only "true crimes" and not "phoney offenses, created by superstition, feudalism, the tax system, and [royal] despotism." He did not list the crimes "created by superstition" (meaning the Christian religion), but these certainly included blasphemy, heresy, sacrilege, and witchcraft, and most probably also incest, bestiality, and same-sex sexual acts, none of which was mentioned in the new Penal Code (promulgated September 26-October 6, 1791). All these former offenses were thus decriminalised." Michael D. Sibalis

See 1810 Code

Age of consent (applied to boys as well as girls) established at age of 11 years. Increased to 13 years in 1863. (Stephen Robertson, "Age of Consent Laws," in Children and Youth in History, Item #230, http://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/teaching-modules/230 |

1793-1794 Goya's Prison Interior and

Yard with Lunatics paintings

1797

Germany Immanuel Kant's The Metaphysics of Morals

About 1792 (Other dates are given) A prison in Northleach,

Gloucestershire, built at the instigation of Sir George Onesiphorus Paul,

High Sheriff of Gloucestershire. Conceived as a model prison. The Prison is

variously known as Gloucester Penitentiary, Gloucester Gaol or Gloucester

Prison.

[Gloucester County Lunatic Asylum was originally planned in 1793

and eventually opened in 1823]

Some features of the prison

were later copied in

Cherry Hill Penitentiary, Philadelphia in 1829, and London's

Pentonville Prison in 1844

new gaols to have one prisoner

per cell, enforced silence

and continuous labour

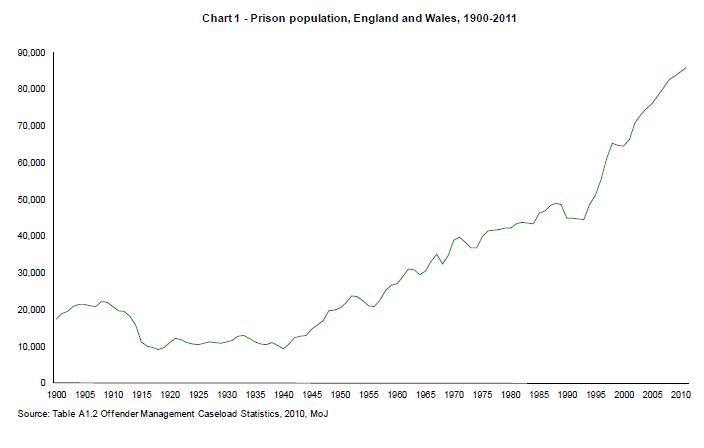

Durkheim (1895, p.65) wrote

"From the beginning of the century, statistics enable us to follow the

course of criminality. It has everywhere increased. In France the increase

is nearly 300 per cent".

|

France: Codes of

1808 and

1810

The Code d'instruction criminelle of 1808 set out the procedures for investigating and judging. See Wikipedia Code pénal de 1810 - a translation into English - see dictionary Established by Napoleon Bonaparte on 12.2.1810. It was later revised, but remained into force until replaced by a new Penal code on 1.3.1994. John Lewis Gillin says that, The Code of 1810 permitted some discretion on the part of the judges. (See 1791 Code)

Revised in 1832 and 1863. Another major reform in 1885 introduced conditional release, deportation for recidivists, and suspended sentences for first-time offenders. |

Britain 1813 Elizabeth Fry's first visit to the women in Newgate

Britain 1815 Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline and Reformation of Juvenile Offenders formed. William Crawford (1788-1847) was a founder member and secretary. See 1833

Britain 1817 Monday morning 24.2.1817: just another mother hanging outside Newgate

|

France: 1818 (Alphonse) Thomas Bérenger published La

Justice criminelle en France, criticising special tribunals, provosts'

courts and military commissions, used under the

Bourbon restoration. According the

1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, Bérenger "advocated a return to the

old common law and trial by jury".

|

| Newgate "now the general felons' prison for the City of London and the County of Middlesex" (James Elmes in A Topographical Description of London (1831). The largest number of prisoners were there for theft, robbery or fraud. Many were children. Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who was a prisoner from 1827 to 1830, described it as "not a house of correction or penitentiary, but merely a prison of detention - a sort of metropolitan watch-house for the secure custody of persons about to be tried or executed...the great mass of prisoners... are persons awaiting trial". The prisoners, like Wakefield, who were there for punishment, were not subject to a regime to make them "penitent". Wakefield, being a gentleman, had quite a commodious cell with a maid-of-all-work to look after him. His two children visited him regularly in his cell where he gave them there lessons. Wakefield was even allowed to carry out social investigations, including interviewing other prisoners. [An early example of field work or participant observation]. Less fortunate prisoners than Wakefield were locked, two or even three together, in cells eight foot by six. Men and women were in different parts of the prison and boys under fourteen were kept in a part of the prison known as the school - unless they were considered hardened offenders. Prisoners sentenced to death were kept in solitary confinement. Wakefield said that, on average, twenty prisoners would be waiting death at any one time. At the most, there were fifty nine. Some of these would be reprieved. There average stay between sentence and reprieve or execution was six weeks. (Bloomfield, P. 1961, chapter 5) |

| France: 1832 8 avril: réforme du Code pénal et création de la détention (art. 7 & 20). La déportation est remplacée transitoirement par la détention perpétuelle (article 17). - (external source) - see dictionary |

1832 The Philanthropic Society opened the Philanthropic School at Redhill opens. With the belief that their work would be more successful away from the streets of London, out in the clean country air. In "1839 A school was established in Mettray near Tours in France and a European movement was begun."

Britain 1833 William Crawford sent on a tour of United States prisons.

"Crawford found two systems in transatlantic prisons: on one hand there was the Auburn 'silent system' which allowed associated labour and dining, but prevented contamination by silence enforced by flogging; on the other hand was the Philadelphia 'separate system' which combined cellular confinement throughout sentence with visits from a battery of reformatory personnel, such as chaplains, teachers, and trade instructors, whose message of forgiveness would hopefully be well-received by prisoners softened by enforced solitude. Crawford was entranced by what he saw as the perfect prison system, and criticized the silent system which, in his view, led to vengefulness and hatred among prisoners. Separation alone, in his view, could deter by its awesome severity and reform by its irresistible impact on the individual conscience." (Bill Forsythe, Dictionary of National Biography)

|

1835 Prisons

Act appointed Prison Inspectors.

These favoured the "Separate System" of stopping prisoners having a bad influence on one another, rather than the "Silent System". Pentonville (below) used the separate system. Victoria Olesen finds marked similarities between Bentham's panopticon plans and the Philadelphia Separate system. Does anyone know of relationships? |

|

|

1838

France Jean Étienne Dominique Esquirol's Des maladies mentales, considées sous les rapports medédical, hygienique et médico-légal published in Paris. Translated into English as Mental Maladies. A Treatise on Insanity in 1845 (Philadelphia) |

| 1839 The first completely separate institution for women and girls in the United States appears to have been established at Mount Pleasant - later known as Ossining - New York, near the Sing Sing male prison in 1835" [1839]. "All other states followed with facilities for women and others for girls" (Norman Johnston 2009) |

|

France: Colonie pénitentiaire de Mettray opened 1840.

Norman Johnston

(2009) says "reformers, shocked by the plight of children

housed in adult prisons, established a minimum security agricultural

facility, the Mettray Colony.... Cottages were arranged on a

campus without walls, a layout that later became a template for American

youth and women's facilities into the 21st century. The individual cottage

was intended to be run as a family unit. Separate institutions for boys and

girls were later opened in most American states, particularly from the

1850s on."

|

Religion and reformation

From the end of July to early October 1841: Elizabeth Fry accompanied her brother and others on a tour of Holland, Germany, Prussia and Denmark. She carried with her a letter of introduction from Prince Albert (Queen Victoria's husband) to the King of Prussia. Their meeting was friendly and concluded with Elizabeth urging the king to mark his reign by "the prisons being so reformed that punishment might become the reformation of criminals; by the lower classes being religiously educated; and by the slaves in their colonies being liberated". (Whitney, J. 1937 p.229) She visited Copenhagen in August 1841. At this time the Danish Prison Commission of 1840 had come to the conclusion that the Auburn (Silent) model was preferable to the Pensylvania (Separate) system for Denmark. Elizabeth Fry campaigned on the importance of religion to changing criminal behaviour and, as a result of her effort, Denmark built one Auburn model prison (Horsens tugthus - opened in 1853) and one Pennsylvania model (vridsløselille - opened in 1859. [Two other Danish prisons: Blegdammens fængsel opened in 1848, Vestre Fængsel in 1895] (Information from Victoria Olesen, history student, Roskilde University in Denmark) |

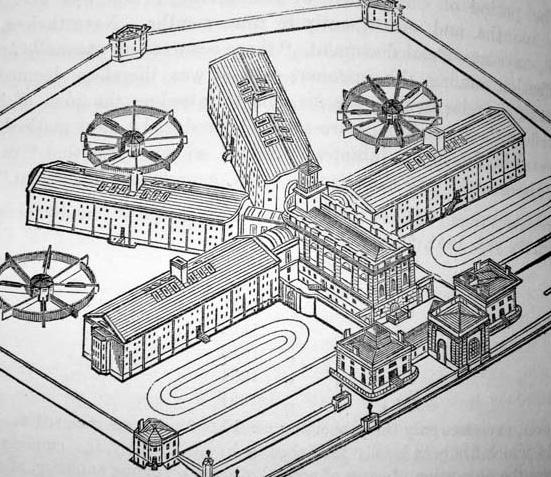

Pentonville

prison, London - 1842 Act

(Constructed on the

separate system

plan - But notice that it is sometimes also called a silent

system)

Isometrical perspective of Pentonville Prison, 1840-1842. Engineer Joshua Jebb (8 May 1793 ? 26 June 1863). Report of the Surveyor-General of Prisons, London, 1844. Image reproduced in Mayhew, Criminal Prisons of London, London, 1862 Joshua Jebb, from Derbyshire, was a military engineer and the British Surveyor-General. He also designed Broadmoor Hospital. (Wikipedia Commons) - See Criminology and Penology logo 2011

In the six years after the opening of Pentonville, 54 prisons were

built on the same plan. Altogether they provided 11,000 separate cells.

External link on heating and ventilation of Pentonville

(scroll down) -

system used at Derby -

Illustrated London News -

history and hanging -

Jebb papers

|

Britain

1847 "Before the 1840s children

received the same treatment in the courts as adults.

Changes began tentatively in 1847 when the Juvenile Offenders Act permitted

children, not over the age of 14, and charged with simple larceny, to be

tried and sentenced by two lay justices of the peace or one stipendiary

magistrate. This was an alternative to the usual full court hearing by

indictment before a jury."

source

29.11.1847 Sir George Grey introduced the Crime and Outrage Bill

(Ireland) bill because of nationalist agitation that was giving the British

government misgivings about a possible violent rebellion against British

rule in Ireland. The Act (Royal assent December 1847) gave the Lord

Lieutenant of Ireland the power to organize districts and bring police into

them at the district's expense. It limited who could own guns and required

all men between age 16 and 60 in a district to help catch murderers when

killings took place or else be guilty of a misdemeanor. See

1850

1850 12.8.1850 In debate on the Crime and Outrage Act (Ireland) Continuance (No. 2) Bill, Sir Andrew Armstrong said:

"What Ireland required was commerce and manufactures to afford remunerative employment to the people, and a home market for its agricultural produce. It was the duty of statesmen to open up the sources of industry and beneficial employment for the people. "The good shepherd would lead his flock." Were the Government prepared with some great and comprehensive measure for placing remunerative employment within the reach of the Irish people? Were they prepared to do battle with the cotton millionaires and the merchant princes of England for a fair share of the commerce and manufactures of the united kingdom for Ireland? Were they prepared to contend against the tyranny of overwhelming capital? Ireland ought to be placed in a state of perfect civil, religious, political, commercial, and manufacturing equality with England. Let the Government charter for a limited term a company of cotton spinners and a company of woolstaplers for each of the three Irish provinces that had no manufactures deserving the name. Let a Royal dockyard be established for building ships for Her Majesty's Navy. Let Ireland have a fair number of representatives in that House. Let the anomaly of the Protestant Church Establishment be abated. With measures like these, the foundation of Ireland's prosperity would be laid, and there would he no need for Coercion Bills." (Hansard 12.8.1850)

1854 An Act of Parliament allowed the court to refer young offenders

to the

Philanthropic Society Reformatory as an alternative to prison.

Reformation was added to

the Society's aims along with prevention and the Society goes

into partnership with the Government who gave money for the boys placed at

the school.

Britain 1857

Prison Hulks cease being used. The Penal Servitude Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict.

c.99) substituted penal servitude for

transportation, except in cases where

a person could be sentenced to transportation for life or for a term not

less than fourteen years. Section 2 of the Penal Servitude Act 1857 (20 &

21 Vict. c.3) abolished the sentence of transportation in all cases and

provided that in all cases a person who would otherwise have been liable to

transportation would be liable to penal servitude instead.

(Wikipedia)

|

1863

France A. M. Guerry Statistique Morale de l'Anglettere compareé avec la statistique morale de la France (The moral statistics of England compared to those of France)

|

|

1876 Frederic Rainer a journeyman printer, and a volunteer with the Church of England Temperance Society wrote to the Society of his concern about the lack of help and hope for those who come before the courts. He gives five shillings and starts the London Police Court Mission. See 1907

|

Neo-classical criminology

Neo-classical criminology adapts classical criminology in the light of positivist thought. It might, for example, argue that most crimes are the result of rational choice, but that an exception must be made for people who are mentally ill. On this distinction, it has been argued that the French Penal Code of 1791 was a strictly classical one, but that subsequent revisions were neo- classical. Others argue that the neo-classical school of thought "emerged between 1880 and 1920, and is still with us today" (external source). Authors who have been identified as neo-classical include James Anson Farrer, Crimes and Punishments, including a new translation of Beccaria's "Dei Delitti e delle Pene.". Published: London : Chatto and Windus, 1880. Henri Joly, Le Crime. Etude sociale. Published: Paris, Versailles [printed], 1888. Gabriel Tarde (1843-1904) and his pupil Raymond Saleilles (1898). |

1880

1884

1885 [March or earlier]

Italy Raffaele Garofalo: Di un criterio positivo della

penalità (Of a positive policy of penalties), Napoli: Leonardo

Vallardi

Italy

Enrico Ferri's Criminal Sociology published in

Italian.

Italy

Enrico Ferri -

La scuola criminale positiva: conferenza del prof. Enrico Ferri

nell'Universit… di Napoli (1885). In his lecture, Enrico Ferri

compares and contrasts the "classical criminal school", starting with

Beccaria, with the

"positive school", starting with

Lombroso and

Garofalo. The classical school used an

"a priori"

method (il metodo aprioristico) of abstract reasoning to relate the

offence to the penalty. It did

not deal with the real offender as such. The positive school began with the

study of facts and was concerned to find the "natural causes" of crime as

well as effective remedies "natural and legal" for it. See

1901

Italy 1885 Raffaele Garofalo: Criminologia: studio sul

delitto, sulle sue cause e sui mezzi di repressione

(Criminology: Study of crime, on its causes and the means of repression)

Torino, Fratelli Bocca. - Translated into French 1887 (Preface, Naples

1.12.1887) La Criminologie: Étude sur la nature du crime

et la théorie de la pénalité - Translated into

English by Robert Wyness Millar as Criminology by

Baron Raffaele Garofalo, with an

introduction by E. Ray Stevens, Boston, Little, Brown and company, 1914.

xl and 478 pages.

|

Sociology - 1893

From Spencer to Durkheim: Herbert Spencer's The Principles of Sociology (1876 on) is in the utilitarian tradition. In industrial society, he argues, a network of individual contracts spontaneously organises society. Individuals seeking their own happiness leads to the good of the whole society and the role of government is restricted to deterring self interest from paths that would harm others. Emile Durkheim's The Division of Labour in Society (1893) argued against Spencer that government (especially its legal aspects) would grow in proportion to the increase in the division of labour. They are inter-dependent and the function of both is not greater happiness, but solidarity.

France Emile Durkheim, in The Division of Labour in Society, provides his sociological definition of crime:

"crime is ... an act which offends strong and defined states of the collective conscience"

Read Durkheim's explanation of what he means by

collective conscience.

You could compare this to Rousseau's General Will.

In The Rules of Sociological Method (1895), he elaborates on this: "There cannot be a society in which the individuals do not differ more or less from the collective type", but what confers the character of criminal on deviants "is not the intrinsic quality of a given act but that definition which the collective conscience lends them". The more powerful the collective conscience, the more it will suppress divergence. But this does not mean crime will be abolished. Instead, the energy of the collective conscience will be exercised against lesser offence against it. Offenses not previously crimes will become crimes. Society needs to penalise acts in order to give more energy to the collective sentiments that they offend. This dialogue between crime and society is necessary to maintain the solidarity of the society. But this is not the only function of crime. Crime is also needed in the evolution of society. "Law and morality vary from one social type to the next" and "they change within the same type if the conditions of life are modified". For this to be possible "the collective sentiments at the basis of morality must not be hostile to change". If they are too strong, they will not be plastic enough to be modified. For change to be possible, the collective sentiments must have only moderate energy.

See below 1920: Fauconnet - A Durkheimian? criminology

|

1893

Italy

La donna delinquente la prostituta e la donna

normale (Criminal Woman, the Prostitute, and the

Normal Woman) by Cesare Lombroso and Guglielmo Ferrero published.

Britain

1895 The Gladstone Report on Prisons:

22.8.1898 Hooligans A Daily Graphic (newspaper) report

wrote of "The avalanche of brutality which, under the name of 'Hooliganism'

... has cast such a dire slur on the social records of South London"." See

Michael Quinion and

Geoffrey

Pearson

1901

22.4.1901 - 23.4.1901 - 24.4.1901 The Positive

School of Criminology Three Lectures given at the University of Naples,

Italy by

Enrico Ferri

in the same hall where he had

lectured in 1885. They were

translated into English by Ernest Untermann and published in

Chicago in 1908.

"We start from the principle that prison treatment should have

as its primary and concurrent objects, deterrence and

reformation"

... it has been proved in every country that punishment does not deter from crime... [If the criminal] "were treated as what he really is he would be eliminated. the shortest and most merciful way would be a painless exit from the world through the lethal chamber; but as a hard-hearted and soft- headed generation would probably object to this on the ground of inhumanity, the next best thing would be isolation for life, say, after three convictions. (page 239) |

1907 The London Police Court Mission staff become 'officers of the court' becoming the national Probation Service in 1938.

1913 Charles Buckman Goring (1870-1919)

The English Convict. A statistical study.

George Herbert Mead

was a lecturer at Chicago University from 1894 until

his death in 1931.

Robert E. Park taught there from 1914 to 1936. His

students included Herbert

Blumer. After the second world war, Chicago

students included

Howard Becker

and

Erving Goffman.

The New Criminology identifies "The Chicago School" as a "legacy of

positivism. In this, it is speaking of the

urban ecology of Robert Park and his colleagues.

"Criminology, as it is understood

to-day, consists of the doctrines of ... three Schools of criminology ....

The

Classical School, after

Beccaria, taught that all criminals were equally responsible in

the eyes of the law ; that they should be punished according to the crimes

they had committed;

but that, despite their wrong-doing, they retained a natural right, common

to all men, to

be humanely treated. The Correctionist School, improving upon its

predecessor, established

the relative responsibility of lunatics and juvenile offenders, and led the

way to our

modern reformatory system. Finally the School of

Lombroso, more

humane still, declared

it was the criminal and not the crime who ought to be studied and punished,

and

expounded a doctrine known as the new science of criminal anthropology.

p.12

"

"prior to his appointment as lecturer in the Department of

Sociology in

1914, Robert Ezra Park had spent some twenty-five years as a

journalist... In the

following twenty years, a mass of research was carried out by

Park's colleagues and students into what they came to call the

social ecology of the city: research into the

distribution of areas of work and residence, places of public intervention

and private retreat, the extent of illness and health, and the urban

concentrations of conformity and deviance. The Chicago School of Sociology,

motivated by the journalist's campaigning and documentary concerns, was the

example par excellence of determined and detailed empirical social

research: a tradition which, for good or ill, is extremely resilient still

in most departments of sociology on the north American continent"

(Young 1973, p. 110)

|

France

1920: Fauconnet - A

Durkheimian? criminology

In 1920, Paul Fauconnet, a colleague of Mauss, Durkheim's nephew, completed his thesis for the University of Paris. This was published as La Responsabilité, Etude de Sociologie [Responsibility. A sociological study] This argued that, historically, it had always been important that someone, or some thing, be held responsible for a crime and punished. If the person who did it could not be clearly identified, someone (or something) else was, and the punishment was carried out. In modern times, criminal responsibility in terms of both intention and of being shown to have committed the act were held to be essential, but the older ideas reveal (Fauconnet argued) the sociological function of punishment. In 1925 wrote the forward to Durkheim's posthumously published lectures (from 1902) L'éducation morale, and in 1932 both books were the focus of discussion and development in Jean Piaget's Le jugement moral chez l'enfant (The Moral Judgement of the Child) |

Chicago, USA Introduction to the Science of Sociology by Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess

Chicago, USA The City by Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess, Roderick D. McKenzie and Louis Wirth. published by University of Chicago Press.

1931 George Bernard Shaw published an essay on "Crude Criminology".

Does anyone know what he said?

|

July 1931

London, England

Association for the Scientific Treatment of Criminals set

up, by the

Tavistock Clinic.

First Annual Report (1932) stated aims as: To initiate and promote scientific research into the causes and prevention of crime. To establish observation centres and clinics for diagnosis and treatment of delinquency and crime To coordinate and consolidate existing scientific work in the prevention of delinquency and crime. To secure cooperation between all bodies engaged in similar work in all parts of the world, and ultimately to promote an international organisation. To assist and advise through the medium of scientific experts the judicial and magisterial bench, the hospitals and government departments in the investigation, diagnosis and treatment of suitable cases. To promote and assist in promoting educational and training facilities for students in the scientific study of delinquency and crime. To promote discussion and to educate the opinion of the general public on these subjects by publications and by other means. |

Chicago, USA. 1934 Mind, Self and Society, from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviourist, lectures and articles by George Herbert Mead, published by his students.

San Francisco, USA. August 1934 Alcatraz became a civilian prison.

Chicago, USA Robert E. Park's "Human ecology" published in the American Journal of Sociology

Chicago, USA Herbert Blumer coined the term symbolic interactionist for theories developed from Mead.

USA

Robert King Merton's "Social Structure and Anomie" published

in the American Sociological Review

1938 Britain: National Probation Service - See

London Police Court Mission

| Britain Leon Radzinowicz established a "Department of Criminal Science" in the Faculty of Law at Cambridge University during World War Two. (source) |

1949

USA

Robert King Merton's

Social Theory and Social Structure.

Towards the codification of theory and research published in United

States. Using the 1957 edition, The New Criminology (1973) drew heavily on

Merton's

idea of anomie. New

Criminology says:

1951

USA

Talcott

Parson's

The Social System published

in United States. This included Parson's description of the sick role as, in

important respects, "deviant"

1958

George Vold's

Theoretical Criminology was, according to

The New Criminology (page 238) "the first criminological textbook to

accord a significant place to crime as a product of social conflict".

"American society... for Merton, has in practice placed undue emphasis on

the

goals behind the game, and has neglected ... the necessity for making

appropriate means universally available. More specifically, Merton argued

that normatively legitimate means have been replaced by (and confused with)

technically efficient means, and, in particular, money has been consecrated

as a value in itself, over and above its use simply for legitimate

consumption. The desire to make money, without regard to the means in which

one sets about doing it, is symptomatic of the malintegration at the heart

of American society." (page 93)

"This book deals with the explanations that contemporary

society has given itself in the past, and continues to give today, to the

enigmatic question of why there is so much crime.Except for purposes of

background and perspective, this book deals only with those areas of theory

that fall within the intellectual orientation usually called 'positivistic'

or 'scientific. ' Only within this orientation are hypotheses and

propositions so formulated that it is possible to examine them in the light

of available information."

| Britain 1959 Leon Radzinowicz founded the "Institute of Criminology", and became the first Wolfson Professor of Criminology. The first Professorship in Criminology in the United Kingdom. (source) |

USA Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin's Delinquency and

Opportunity: a Theory of Delinquent Gangs

New Criminology describes Cloward and Ohlin as theorists of

subcultures:

"The subculture theorists, following

Merton

[considered] the existence of anomie implied that cultural goals were

widely diffused and internalised, but there was no corresponding

internalisation (or

institutionalisation) of the means of

achieving them" (page 133)

|

18.5.1964 "Mods and Rockers jailed after seaside riots" (BBC On this day)

|

Criminology for Criminals

|

In the 1960s and 1970s, deviancy theory took a special interest in looking at the world through the eyes of the deviant.

"To live outside the law you must be honest

I know you always say that you agree

Alright, so where are you tonight...?"

Bob Dylan: "Absolutely Sweet Marie" quoted as the frontispiece to The New Criminology

USA Howard Becker's "Whose Side are We On?" published in Social Problems

July 1968 United Kingdom National Deviancy Symposium formed - See Wikipedia

1971 United Kingdom Jock Young The Drugtakers. The Social Meaning of Drug Use published as a Paladin paperback. Jock Young was "Senior lecturer in sociology at Enfield College of Technology and a member of the National Symposium in Deviancy, a radical group of criminologists" [Yes... It does say "in deviancy"]

United Kingdom Daily Mail 17.8.1972 "As Crimes of Violence Escalate, a word Common in the United States Enters the British Headlines: Mugging. To our Police, it's a frightening new strain of crime". (quoted Hall and others 1978, p.3)

United Kingdom 5.11.1972 Unprovoked attack on Robert Keenan by Paul Storey, James Duignan and Mustafa Fuat in Handsworth, Birmingham. Attacks repeated over a period of over two hours. The attackers were aged 15 to 16. ( Hall and others 1978, pp 81 following)

|

Moral panic theory

Britain 1972 Stanley Cohen's Folk Devils and Moral Panics: the creation of the Mods and Rockers - See mods and rockers

"Societies appear to be subject, every now and then, to periods of moral panic. A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions, ways of coping are evolved" (p.9) |

United Kingdom 19.3.1973 Paul Storey pleaded guilty to attempted murder and robbery; James Duignan and Mustafa Fuat to wounding with intent to cause grievous bodily harm and robbery. Paul Storey was sentenced to twenty years and the other two to twenty years. This case was the stimulus and major case study content of Policing the Crisis in 1978. ( Hall and others 1978, pp 81 following and p.viii)

United Kingdom Ian Taylor, Paul Walton and Jock Young published The New Criminology: For a Social Theory of Deviance . Acknowledgements: "This book is fundamentally the product of discussions and developments in and around the National Deviancy Conference, a growing body of sociologists and individuals involved in social action in the United Kingdom"

United Kingdom New directions in sub-cultural theory, by Jock Young, published in John Rex's introduction to major trends in British sociology

France (English Translation 1977:) Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison

United Kingdom

Critical Criminology by Taylor, Walton and Young,

Friday 1.4.1977 - Sunday 3.4.1977 National Deviancy Conference, Sheffield.

Frank Pearce on ontological insecurity in relation to sexual relations

between adults and children.

|

United Kingdom

Policing the Crisis: "Mugging" the State and Law and Order by Stuart Hall, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke and Brian Roberts Emma Dowling 2013: "It provided the analytical tools to interpret how a social phenomenon was objectified and transformed into a moral panic, ultimately becoming a pressing issue of the day. Its authors sought to unearth the relations of social forces that were obscured by portrayals of urban streets 'infested with violent hoodlums' that dominated the public eye and constructed an ideology of crisis in which the police force turned into the only bulwark against the breakdown of social order. 'Aggro Britain', as it was described in the 1970s, referred to a constructed social crisis centred on street crime, although the call for 'policing the crisis', in fact, derived from the anxiety caused by growing political, economic and racial conflict." |

|

What is to Be Done?

1979: Beyond left idealism 1981: Swamp 81. 1982: Paul Gilroy "Police and thieves" 1984: What is to be Done About Law and Order - Crisis in the Eighties by John Lea and Jock Young

|

1979

United Kingdom Free-market/Authoritarian Right win control of UK

Government. (See

social science timeline)

Jock Young "Left idealism, reformism and beyond: from new criminology to

Marxism" - Criticised by Paul Gilroy in

Police and thieves in 1982.

1981

United Kingdom Saturday 11.4.1981: Swamp 81 against black crime in

Brixton began. Serious riot followed. Start of the "worst civil unrest seen

on British streets this century." During the summer the rioting spread to

Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds.

1982

Early 1982

The Empire Strikes Back contains "Police and thieves" by

Paul Gilroy.

United Kingdom Ian Taylor's Law and Order: Arguments for

Socialism

1983

Lee Bridges "Extended Views; The British Left and Law and Order", Sage

Race Relations Abstracts volume eight, pages 19-26 was summarised in

What is to be Done About Law and Order as "the most clear

exposition" of the "politics" of Paul Gilroy and Lee Bridges

USA

1983: Murder of prison officers followed by "permanent

lockdown" at Marion, Illinois.

1984

United Kingdom What is to be Done About Law and Order - Crisis in

the Eighties by John Lea and Jock Young published as a Penguin

paperback. Chapter 8 A Realistic Approach to Law and Order spoke

about

January 1984 UK Home Office Circular 8/84:

1985

1986

United Kingdom 1986: Centre for Criminology established at

Middlesex Polytechnic (later

University) to

develop interdisciplinary research into crime and the criminal justice

system

1987

United Kingdom The increase in crime in England and Wales during

the present government 1979-1986 with comparisons with the 1975-1978

period by Jock Young, Middlesex Polytechnic Centre for Criminology

John Lea:

Left Realism: A Defence

"a schizophrenia about crime on the left where crimes against

women and immigrant groups were quite rightly an object of concern, but

other types of crime were regarded as being of little interest or somehow

excusable."

"A primary objective of the police has always been the prevention of crime.

However, since some of the factors affecting crime lie outside the control

or direct influence of the police, crime prevention can not be left to them

alone. Every individual citizen and all those agencies whose policies and

practices can influence the extent of crime should make their contribution.

Preventing crime is a task for the whole community."

| Cultural Critiques: Once Durkheim asks the question "what is crime", and answers it in relation to the whole society, there is the possibility that the study of crime will become a study of society. John Lea finds the same possibility in Marx and Engels. The scope of criminology becomes global: Frank Pearce analyses concepts of socialism in the light of durkheimian and marxist approaches to crime. Jayne Mooney and Jock Young discuss celebrity culture and the celebration of crime. Ian Taylor puts "crime in context" in "A Critical Criminology of Market Societies". John Lea's talk to the Middlesex University Criminology Society is given here as an example of criminology analysing a global issue. |

Frank Pearce's The Radical Durkheim analysed the crime theories of Engels and Marx and their followers along with those of Durkheim and Jock Young and his colleagues in relation to the theoretical possibility that crime might be eliminated under socialism.

November 1990 United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher replaced by John Major as Conservative Prime Minister.

Roger Matthews and Jock Young Issues in Realist Criminology and Rethinking Criminology: The Realist Debate "A companion volume to Issues in realist criminology edited by Roger Matthews and Jock Young". Sage Contemporary Criminology series. London: Sage

| John Lea: Criminology and postmodernity | What is postmodernity? |

"How are ruling and subordinate groups and classes in society actually deploying criminal law and criminalisation?" |

May 1997 United Kingdom New Labour Prime Minister elected to be "tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime"

John Lea: From integration to exclusion: the development of crime prevention policy in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom The New Criminology Revisited: A collection of articles edited by Paul Walton and Jock Young.

United Kingdom Ian Taylor's Crime in Context. A Critical Criminology of Market Societies

United Kingdom Jock Young's The Exclusive Society: Social Exclusion, Crime and Difference in Late Modernity

United Kingdom

July 2000 News of the World "name and shame" campaign respecting alleged paedophiles provoked vigilante violence.

19.1.2001 Death of Ian Taylor [external link to Jock Young's memorial of Ian in The Guardian]

March 2001 Symposium held in honour of Leon Radzinowicz at Cambridge University. The subsequent book (Bottoms and Tonry 2002) included an appreciation, by Anthony Bottoms, recollections by Roger Hood, (Theory:) "Ideology and crime - a further chapter" by David Garland, "Morality, crime, compliance and public policy" by Anthony Bottoms, (History:) "Gentlemen convicts, dynamitards and paramilitaries: the limits of criminal justice", by Sean McConville, "The English police: a unique development" by Clive Emsley, (Prisons) "A 'liberal regime within a secure perimeter'?: dispersal prisons and penal practice in the late twentieth century" by Alison Liebling, (Policy) "Criminology and penal policy: the vital role of empirical research" by Roger Hood and a Radzinowicz bibliography

Peter Kennison, Policing Black People: A Study of Ethnic Relations as Seen Through the Police Complaints System Middlesex University, 2001 PhD thesis.

12.11.2002-16.11.2002 The 2002 American Society of

Criminology

Conference at The University of Pennsylvania included

Critical Criminology in the Twenty First Century: Critique, Irony and the

Always Unfinished by Jock Young

ABSTRACT

Critical Criminology is the criminology of the late modernity in that it

arose at the cusp of change in the last third of the twentieth century and

that its sensitivity to the social construction of reality and the

blurring, pluralism and contested nature of norms best fits the grain of

every day life today. The development within critical criminology of ten

key ironies as a sustained challenge to the taken for granted assumptions

about crime and the criminal justice system has even more relevance at the

beginning of the twenty first century as it did in the 1970's. A critique

of the revisionist history of critical criminology as presented in the work

of David Garland with its emphasis on the past and momentary nature of the

critical tradition. Instead an examination of the flourishing of critical

criminology and its position as the major opponent of neo-liberalism. The

need to develop a criminology which despite scepticism about meta-

narratives of progress does not lapse into a postmodernist nihilism but

tackles full on the problems of social transformation amid an open-ended

narrative ever aware of the changing and contested nature of social justice

A discussion of the of the work of Nancy Fraser and Zygmunt Bauman in this

respect

and

Celebrity, Late Modernity and the Celebration of

Crime by Jayne Mooney and Jock Young.

ABSTRACT

The economic and social changes concomitant with globalisation give rise to

the identity crises of late modernity. The shift occurs from the politics

of

class to the identity politics and the stratifications of status and

celebrity, witness the work of Nancy Fraser and Lawrence Friedman. The

uncertainties of identity leads to the seeking out of both positive and

negative points of orientation: bright and dark stars of fixed position.

Thus at the same time as we have a demonisation (othering) of the

underclass we have the idealisation of the celebrity. Both crime and

celebrity become the basic commodities of the spectaclre [spectacle?].

Contradictions and crossover in the discourses of success and failure give

rise to the nemesis and cronus effects. The detachment of vocabularies of

motive from fixed structural position in late modernity results in free

floating, mediated discourses which both shape crime and evoke celebrity;

the Mafia and images of Serial Killers are used as examples.

Peter Kennison and David Swinden,

Behind the Blue Lamp: Policing North and East London

2004

Nils Christie A Suitable Amount of Crime London:

Routledge:

"Crime does not exist. Only acts exist, acts often given

different meanings within various

social frameworks. Acts and the meanings given to them are our data. Our

challenge is to follow the destiny of acts through the universe of

meanings. Particularly, what are the social conditions that encourage or

prevent giving the acts the meaning of being crime?" (Christie, 2004: p.3)

"crimes are in endless supply. Acts with the potentiality of

being seen as crimes are like an unlimited natural resource. We can take

out a little in the form of crime-or a lot". (Christie, 2004:

p.10)

|

2004:

Criminology and History John Lea's internet

guide.

Students and staff were equally pleased to listen to one the world's most cited criminologists make every part of his lecture clear and fascinating - Just as he has at every lecture since I first heard him thirty five years ago. John's topic, "Terrorism, Crime and the Collapse of Civil Liberties" began with an exposition of one law. He explained clearly the constitutional arguments against the United Kingdom's 2005 Prevention of Terrorism Act. Although it "might be argued that terrorism is a special case and requires special measures", John outlined other erosions of established legal safeguards in a succession of United Kingdom criminal laws. By now anxious about the open, legal state, we slipped into a greater state of anxiety as John explored law's intersection with the global secret state. He talked about "the formation of a new type of globalised system of coercive information extraction" since the destruction of the World Trade Centre in September 2001 and the subsequent war to control Afghanistan. The first stage was establishing Guantánamo Bay in Cuba for the reception of those to be interrogated - And claiming it as an area of United States administration outside the protection of United States law and, in certain respects, outside of international law. The secret state seeks to be secret, but John claimed enough has been revealed about Guantánamo to recognise it as intersecting with UK law and security, and not just the responsibility of the United States. British citizens recently released from Guantánamo have said that they were interviewed by British security service (MI6) officers whilst they were there. Since the US legal system has asserted its jurisdiction over any territory administered by the United States, Guantánamo's usefulness has declined and has been replaced by a system of truly international interrogation. John documented reports of large numbers of people who "disappear" and are sent for interrogation in countries where the US courts cannot reach them.

"There are now possibly up to 10,000 ghost detainees in this new global system of incarceration and interrogation and permanent detention without trial". This secret international system intersects with the provisions of national law openly debated and processed through Parliament. The 2005 Prevention of Terrorism Act allows the Home Secretary to issue a control order on the basis of "reasonable suspicion" that someone is involved in terrorist activity. John argued that "some of the evidence" leading to this suspicion may come, via the UK security services, from the USA. "In short, evidence extracted by coercive interrogation may find itself into the working of the new British anti-terror regime". By focusing on one law and its inter-relationships, John sought to show that the threat to civilised, liberal, society is much much wider than one law. Part of his argument, somewhat mysteriously called "trickle up", is that "anti-terrorist" developments are not a simple response to terrorism, but a single feature of a general turning away from the "steady growth in the stability of international legality" since the second world war. They are just one element in the move towards what international lawyer Philip Sands has called "A Lawless World" (Sands 2005). The dirty water also "trickles down", contaminating public standards and expectations of the rule of law, and undermining liberty in areas unrelated to terrorism. What we are looking at, according to John's title, is a "collapse of civil liberties". Our pond of national law now sloshes about in a global ocean. Placing UK law in the context of the global secret state was a strength of John's analysis. Its inevitable weakness was not having time to place that in the context of a changing world political structure. What began as criticism of a single national law, ended, for me, with unanswered questions about the fate of liberty in a post-national world and what international measures might defend it. "Terrorism, Crime and the Collapse of Civil Liberties" is available as work in progress at http://www.bunker8.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/misc/terror.htm. John Lea's talk was the third in a series of well-attended events organised by Middlesex University Criminological Society this year. Student organiser Fitzroy Maxwell (Max), who has himself given enormous enthusiasm and energy to organising the events, credited their success to team work. |

29.11.2005 Crime and the Community

Crime and Conflict Research Centre developed by sociologists and criminologists at Middlesex University

Monday 6.3.2006: Crime and Conflict Research Centre website live at http://www.mdx.ac.uk/hssc/research/csccc/index.htm

7.12.2010 Breaking the Cycle:Effective Punishment, Rehabilitation and Sentencing of Offenders Green paper. cm 7972 available for download at hhtp://www.official-documents.gov.uk and hhtp://www.justice.gov.uk

Headings

Common Law and medieval prisons

Felonies and the death penalty

1487: Hammer of the Witches

1562/1563: Witchcraft Acts

1614: Transportation

1660: John Bunyan in prison

1674: Old Bailey Proceedings

1832: Philanthropic School

1839: Mount Pleasant Women's Prison

1840: Mettray

1842 Pentonville

1845 Telegraph

Engels' and Marx's positivism?

1849 Winson Green

1851 Wandsworth

1852 Holloway

1853 Penal Servitude

1861 Death Penalty restriction

1863 Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum and Parkhurst Women's Prison

1893: Sociology

1898: Hooligans

1938: National Probation Service

1972: mugging

1985: New Holloway Prison

Index

Take a Break - Read a Poem

Take a Break - Read a Poem