Quotes from

Robert Park -

Ernest Burgess

Roderick McKenzie and

Louis Wirth

Concepts for Human Ecology

1921 Introduction to the

Science of

Sociology

1925 The City

The city: suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the urban environment

The growth of the city: an introduction to a research project

The ecological approach to the study of the human community

Community organisation and the romantic temper

Magic, mentality, and city life

A Bibliography of the Urban Community

1944 An Autobiographical Note

1925 The City

The city: suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the urban environment

The growth of the city: an introduction to a research project

The ecological approach to the study of the human community

Community organisation and the romantic temper

Magic, mentality, and city life

A Bibliography of the Urban Community

1944 An Autobiographical Note

Park, R.E. and Burgess, E.W. 1921 Introduction to the Science of Sociology .

Note: Extracts credited to Introduction to the Science of Sociology are

taken from

another web site, which does not credit them. I believe the

credit is

correct, but have not obtained a copy of the original to check.

Competition a Process of Interaction

Of the four great types of interaction - competition - conflict - accommodation, and assimilation - competition is the elementary, universal and fundamental form. Social contact ... initiates interaction. But competition, strictly speaking, is interaction without social contact.

... in human society competition is always complicated with other processes, that is to say, with conflict, assimilation, and accommodation.

It is only in the plant community that we can observe the process of competition in isolation, uncomplicated with other social processes. The members of a plant community live together in a relation of mutual interdependence which we call social probably because, while it is close and vital, it is not biological. It is not biological because the relation is a merely external one and the plants that compose it are not even of the same species. They do not interbreed. The members of a plant community adapt themselves to one another as all living things adapt themselves to their environment, but there is no conflict between them because they are not conscious. Competition takes the form of conflict or rivalry only when it becomes conscious, when competitors identify one another as rivals or as enemies.

This suggests what is meant by the statement that competition is interaction without social contact.. It is only when minds meet, only when the meaning that is in one mind is communicated to another mind so that these minds mutually influence one another, that social contact, properly speaking, may be said to exist.

On the other hand, social contacts are not limited to contacts of touch or sense or speech, and they are likely to be more intimate and more pervasive than we imagine. Some years ago the Japanese, who are brown, defeated the Russians, who are white. In the course of the next few months the news of this remarkable event penetrated, as we afterward learned, the uttermost ends of the earth. It sent a thrill through all Asia and it was known in the darkest corners of Central Africa. Everywhere it awakened strange and fantastic dreams. This is what is meant by social contact.

a)

Competition

and Competitive Co-operation.

Social contact, which inevitably initiates

conflict,

accommodation, or

assimilation, invariably creates also sympathies, prejudices,

personal and

moral relations which modify, complicate, and control competition. On the

other hand, within the limits which the cultural process creates, and

custom, law, and tradition impose, competition invariably tends to create

an impersonal social order in which each individual, being free to pursue

his own profit, and, in a sense, compelled to do so, makes every other

individual a means to that end. In doing so, however, he inevitably

contributes through the mutual exchange of services so established to the

common welfare.

If we are to assume that the

economic order is fundamentally ecological,

that is, created by the struggle for existence, an organisation like that

of the plant community in which the relations between individuals are

conceivably at least wholly external, the question may be very properly

raised why the competition and the organisation it has created should be

regarded as social at all. As a matter of fact sociologists have generally

identified the social with the moral order, and

Dewey, in his

Democracy and

Education, makes statements which suggest that the purely

economic order,

in which man becomes a means rather than an end to other men, is unsocial,

if not antisocial.

The fact is, however, that this character of externality in human relations

is a fundamental aspect of

society and social life. It is merely another

manifestation of what has been referred to as the

distributive aspect of

society. Society is made up of individuals

spatially separated,

territorially distributed, and capable of independent locomotion. This

capacity of independent locomotion is the basis and the symbol of every

other form of independence. Freedom is fundamentally freedom to move and

individuality is inconceivable without the capacity and the opportunity to

gain an individual experience as a result of independent action.

On the other hand, it is quite true that society may be said to exist only

so far as this independent activity of the individual is controlled in the

interest of the group as a whole. That is the reason why the problem of

control, using that term in its evident significance, inevitably becomes

the central problem of sociology.

c)

Competition

and Control

Competition is universal in the world of living things. Under

ordinary

circumstances it goes on unobserved even by the individuals who are most

concerned. It is only in periods of crisis, when men are making new and

conscious

efforts to control the conditions of their common life, that the

forces with which they are competing get identified with persons, and

competition is converted into

conflict. It is in

what has been described as

the political process that society

consciously deals with its crises. War

is the political process par excellence. It is in war that the great

decisions are made. Political organisations exist for the purpose of

dealing with conflict situations. Parties, parliaments and courts, public

discussion and voting are to be considered simply as substitutes for war.

d)

Accommodation,

Assimilation, and

Competition

Conflict

is then to be identified with the political order and with

conscious control.

Accommodation, on the other hand, is associated with the

social order that is fixed and established in custom and the mores.

Assimilation, as distinguished from accommodation, implies a more

thoroughgoing transformation of the personality--transformation which takes

place gradually under the influence of social contacts of the most concrete

and intimate sort.

Accommodation may be regarded, like religious conversion, as a kind of

mutation. The wishes are the same but their organisation is different.

Assimilation takes place not so much as a result of changes in the

organisation as in the content, i.e., the memories, of the personality. The

individual units, as a result of intimate association, interpenetrate, so

to speak; and come in this way into possession of a common experience and a

common tradition. The permanence and solidarity of the group rest finally

upon this body of common experience and tradition. It is the role of

history to preserve this body of common experience and tradition, to

criticise and reinterpret it in the light of new experience and changing

conditions, and in this way to preserve the continuity of the social and

political life.

The relation of social structures to the processes of

competition,

conflict,

accommodation, and

assimilation may be represented schematically

as follows:

...

b)

Competition

and Freedom

...

The

economic

organisation

of society, so far as it is an effect of free

competition, is an

ecological organisation. There is a

human as well as a

plant and an

animal ecology.

...

Conflict,

assimilation and

accommodation as

distinguished from competition are all intimately related to control.

Competition is the process through which the

distributive

and ecological

organisation of society is created. Competition determines the distribution

of population territorially and vocationally. The division of labour and

all

the vast organised

economic interdependence of individuals and groups of

individuals characteristic of modern life are a product of

competition. On

the other hand, the moral and political order, which imposes itself upon

this competitive organisation, is a product of

conflict,

accommodation

and

assimilation.

...

Accommodation, on the

other hand, is the process by which the individuals and groups make the

necessary internal adjustments to social situations which have been created

by

competition and

conflict. War and

elections change situations. When

changes thus effected are decisive and are accepted, conflict subsides and

the tensions it created are resolved in the process of accommodation into

profound modifications of the competing units, i.e., individuals and

groups. A man once thoroughly defeated is, as has often been noted, "never

the same again." Conquest, subjugation, and defeat are psychological as

well as social processes. They establish a new order by changing, not

merely the status, but the attitudes of the parties involved. Eventually

the new order gets itself fixed in habit and custom and is then transmitted

as part of the established social order to succeeding generations. Neither

the physical nor the social world is made to satisfy at once all the wishes

of the natural man. The rights of property, vested interests of every sort,

the family organisation, slavery, caste and class, the whole social

organisation, in fact, represent accommodations, that is to say,

limitations of the natural wishes of the individual. These socially

inherited accommodations have presumably grown up in the pains and

struggles of previous generations, but they have been transmitted to and

accepted by succeeding generations as part of the natural, inevitable

social order. All of these are forms of control in which

competition is

limited by status.

| SOCIAL PROCESS | SOCIAL ORDER | Competition | The economic equilibrium | Conflict | The political order | Accommodation | Social organisation | Assimilation | Personality and the cultural heritage |

The Concept of Conflict

The distinction between

competition

and

conflict has

already been indicated. Both are forms of

interaction, but

competition is a struggle between individuals, or groups of individuals,

who are not necessarily in contact and communication; while conflict is a

contest in which contact is an indispensable condition. Competition,

unqualified and uncontrolled as with plants, and in the great impersonal

life-struggle of man with his kind and with all animate nature, is

unconscious. Conflict

is always

conscious, indeed, it evokes the deepest

emotions and strongest passions and enlists the greatest concentration of

attention and of effort. Both competition and conflict are forms of

struggle. Competition, however, is continuous and impersonal, conflict is

intermittent and personal.

Competition is a struggle for position in an

economic order. The

distribution

of populations in the world-economy, the industrial

organisation in the national economy, and the vocation of the individual in

the division of labour - all these are determined, in the long run, by

competition. The status of the individual, or a group of individuals, in

the social order, on the other hand, is determined by rivalry, by war, or

by subtler forms of conflict.

The notion of conflict, like the fact, has its roots deep in

human

interest.

Mars has always held a high rank in the hierarchy of the gods.

Whenever and wherever struggle has taken the form of conflict, whether of

races, of nations, or of individual men, it has invariably captured and

held the attention of spectators. And these spectators, when they did not

take part in the fight, always took sides. It was this conflict of the

non-combatants that made public opinion, and public opinion has always

played an important role in the struggles of men. It is this that has

raised war from a mere play of physical forces and given it the tragic

significance of a moral struggle, a conflict of good and evil.

Adaptation and accommodation

The

term adaptation came into vogue with

Darwin's theory of

the origin of the species by natural

selection. This theory was based upon the observation that no two members

of a biological species or of a family are ever exactly alike. Everywhere

there is variation and individuality. Darwin's theory assumed this

variation and explained the species as the result of natural selection. The

individuals best fitted to live under the conditions of life which the

environment offered, survived and produced the existing species. The others

perished and the species which they represented disappeared. The

differences in the species were explained as the result of the accumulation

and perpetuation of the individual variations which had "survival value."

Adaptations were the variations which had been in this way

selected and

transmitted.

The term

accommodation is a kindred concept with a slightly different

meaning. The distinction is that

adaptation is applied to organic

modifications which are transmitted biologically; while accommodation is

used with reference to changes in habit, which are transmitted, or may be

transmitted, sociologically, that is, in the form of social tradition.

The outcome of the

adaptations and

accommodations, which the struggle for

existence enforces, is a state of relative

equilibrium among the competing species and individual members

of these species. The equilibrium which is established by adaptation is

biological, which means that, in so far as it is permanent and fixed in the

race or the species, it will be transmitted by biological inheritance.

The

equilibrium based on

accommodation, however, is not biological;

it is economic and social and is transmitted, if at all, by tradition. The

nature of the

economic equilibrium which results from competition has been

fully described in chapter viii. The plant community is this equilibrium in

its absolute form.

In animal and human

societies the

community has, so to speak, become

incorporated in the individual members of the group. The individuals are

adapted to a specific type of communal life, and these

adaptations, in

animal as distinguished from human societies, are represented in the

division of labour between the sexes, in the instincts which secure the

protection and welfare of the young, in the so-called gregarious instinct,

and all these represent traits that are transmitted biologically. But human

societies, although providing for the expression of original tendencies,

are organised about tradition, mores, collective representations, in short,

consensus.. And consensus represents, not

biological adaptations, but

social accommodations.

Social organisation, with the exception of the order based on competition

and

adaptation, is essentially an

accommodation of differences through

conflicts. This fact explains why diverse-mindedness rather than

like-mindedness is characteristic of human as distinguished from animal

society.

The City

R.E. Park

1925/1

"The city: suggestions for the

investigation of human

behaviour in the urban environment"

Chapter one in

The City (pages 1-46)

The city , from the point of view of this paper, is something

more than a

congeries of individual men and of social conveniences - streets,

buildings, electric lights, tramways, and telephones, etc.; something more,

also, than a mere constellation of institutions and administrative devices

-courts, hospitals, schools, police, and civil functionaries of various

sorts. The city is, rather, a state of mind, a body of customs and

traditions, and of the organised attitudes and sentiments that inhere in

these customs and are transmitted with this tradition. The city is not, in

other words, merely a physical mechanism and an artificial construction. It

is involved in the vital processes of the people who compose it; it is a

product of nature, and particularly of human nature.

The city has, as

Oswald Spengler has recently pointed out, its own

culture:

The city has been studied, in recent times, from the point of view of its

geography, and still more recently from the point of view of its ecology.

There are forces at work within the limits of the urban community - within

the limits of any

natural area of human habitation, in fact - which tend to

bring about an orderly and typical grouping of its population and

institutions. The science which seeks [p.2]

to isolate these factors and to describe the typical constellations of

persons and institutions which the co-operation of these forces produce, is

what we call human, as distinguished from plant and animal, ecology.

Transportation and communication, tramways and telephones, newspapers and

advertising, steel construction and elevators - all things, in fact, which

tend to bring about at once a greater mobility and a greater concentration

of the urban populations - are primary factors in the ecological

organisation

of the city.

The city is not, however, merely a geographical and ecological unit; it is

at the same time an economic unit. The

economic organisation of the city is

based on the division of labour. The multiplication of occupations and

professions within the limits of the urban population is one of the most

striking and least understood aspects of modern city life. From this point

of view, we may, if we choose, think of the city, that is to say, the place

and the people, with all the machinery and administrative devices that go

with them, as organically related; a kind of psychophysical mechanism in

and through which private and political interests find not merely a

collective but a corporate expression.

Much of what we ordinarily regard as the city - its charters, formal

organisation, buildings, street railways, and so forth - is, or seems to

be, mere artifact. But these things in themselves are utilities,

adventitious devices which become part of the living city only when, and in

so far as, through use and wont they connect themselves, like a tool in the

hand of man, with the vital forces resident in individuals and in the

community.

Anthropology, the science of man, has been mainly concerned up

to the present with the study of primitive peoples. But civilised man is

quite as interesting an object of investigation, and at the same time his

life is more open to observation and study. Urban life and

culture are more

varied, subtle, and complicated, but the fundamental motives are in both

instances the same. The same patient methods of observation which

anthropologists like

Boas and

Lowie have expended on the study of the life and

manners of the North American Indian might be even more fruitfully employed

in the investigation of the customs, beliefs, social practices, and

general conceptions of life prevalent in Little Italy on the lower North

Side in Chicago, or in recording the more sophisticated folk- ways of the

inhabitants of Greenwich Village and the neighbourhood of Washington

Square, New York.

We are mainly indebted to writers of fiction for our more intimate

knowledge of contemporary urban life. But the life of our cities demands a

more searching and disinterested study than even

Emile Zola has given us in

his "experimental" novels and the annals of the Rougon-Macquart family.

We need such studies, if for no other reason than to enable us

to read the newspapers intelligently. The reason that the daily

chronicle of the newspaper is so shocking, and at the same time so

fascinating, to the average reader is because the average reader knows so

little about the life of which the newspaper is the record.

The observations which follow are intended to define a point of

view and to indicate a program for the study of urban life: its physical

organisation, its occupations, and its

culture.

[p.12]

II. Industrial organisation and the moral order

The ancient city was primarily a fortress, a place of refuge in time of

war. The modern city, on the contrary, is primarily a convenience of

commerce, and owes its existence to the market place around which it sprang

up. Industrial competition and the division of labour, which have probably

done most to develop the latent powers of mankind, are possible only upon

condition of the existence of markets, of money, and other devices for the

facilitation of trade and commerce.

An old German adage declares that "city air makes men free" (Stadt Luft

macht frei). This is doubtless a reference to the days when the free

cities of Germany enjoyed the patronage of the emperor, and laws made the

fugitive serf a free man if he succeeded for a year and a day in breathing

city air. Law, of itself, could not, however, have made the craftsman free.

An open market in which he might sell the products of his labour was a

necessary incident of his freedom, and it was the application of the money

economy to the relations of master and man that completed the emancipation

of the serf.

Vocational classes and vocational types. - The old adage which

describes the city as the natural environment of the free man still holds

so far as the individual man finds in the chances, the diversity p of

interests and tasks, and in the vast unconscious co-operation of city life

the opportunity to choose his own vocation and develop his peculiar

individual talents. The city offers a market for the special talents of

individual men. Personal competition tends to select for each special task

the individual who is best suited to perform it.

There are some sorts of industry, even of the lowest kind, which can be

carried on nowhere but in a

great town."

(Adam Smith -

The Wealth of Nations, pp.

28-29)

Success, under conditions of personal competition, depends upon

concentration upon some single task, and this concentration stimulates the

demand for rational methods, technical devices, and exceptional skill.

Exceptional skill, while based on natural talent, requires special

preparation, and it has called into existence the trade and professional

schools, and finally bureaus for vocational guidance. All of these, either

directly or indirectly, serve at once to select and emphasize individual

differences.

Every device which facilitates trade and industry prepares the way for a

further division of labour and so tends further to specialize the tasks in

which men find their vocations.

The outcome of this process is to break down or modify the older

social and

economic organisation of society, which was based on family

ties, local

associations, on culture, caste, and status, and to

[p.14]

substitute for it an organisation based on occupation and vocational

interests.

In the city every vocation, even that of a beggar, tends to assume the

character of a profession and the discipline which success in any vocation

imposes, together with the associations that it enforces, emphasizes this

tendency-the tendency, namely, not merely to specialize, but to rationalize

one's occupation and to develop a specific and conscious technique for

carrying it on.

The effect of the vocations and the division of labour is to produce, in

the

first instance, not social groups, but vocational types: the actor, the

plumber, and the lumber-jack. The organisations, like the trade and labour

unions which men of the same trade or profession form, are based on common

interest* In this respect they differ from forms of association like the

neighbourhood, which are based on contiguity, personal

association, and the

common ties of humanity. The different trades and professions seem disposed

to rt. group themselves in classes, that is to say, the artisan, business,

and professional classes. But in the modern democratic state the classes

have as yet attained no effective organisation. Socialism, founded on an

effort to create an organisation based on "class consciousness,'*^-has

never succeeded, except, perhaps, in Russia, in creating more than a

political party.

The effects of the division of labour as a discipline, i.e., as means of

molding character, may therefore be best studied in the vocational types it

has produced. Among the types which it would be interesting to study are:

the shopgirl, the policeman, the peddler, the cabman, the nightwatchman,

the clairvoyant, the vaudeville performer, the quack doctor, the bartender,

the ward boss, the strike-breaker, the labour agitator, the school teacher,

the reporter, the stockbroker, the pawnbroker; all of these are

characteristic products of the conditions of city life; each, with its

special experience, insight, and point of view determines for each

vocational group and for the city as a whole its individuality.

[p.23]

Secondary relations and social control

Modern methods of urban transportation and communication- the electric

railway, the automobile, the telephone, and the radio- have silently and

rapidly changed in recent years the social and industrial organisation of

the modern city. They have been the means of concentrating traffic in the

business districts, have changed the whole character of retail trade,

multiplying the residence suburbs and making the department store possible.

These changes in the industrial organisation and in the

distribution of

population have been accompanied by corresponding changes in the habits,

sentiments, and character of the urban population.

The general nature of these changes is indicated by the fact that the

growth of cities has been accompanied by the substitution of indirect,

"secondary," for direct, face-to-face, "primary" relations in the

associations of individuals in the community.

[p.24]

Touch and sight, physical contact, are the basis for the first and most

elementary human relationships. Mother and child, husband and wife, father

and son, master and servant, kinsman and

neighbour, minister, physician,

and teacher-these are the most intimate and real relationships of life, and

in the small community they are practically inclusive.

The

interactions which take place among the members of a community

so

constituted are immediate and unreflecting. Intercourse is carried on

largely within the region of instinct and feeling. Social control arises,

for the most part spontaneously, in direct response to personal influences

and public sentiment. It is the result of a

personal accommodation, rather

than the formulation of a rational and abstract principle.

The church, the school, and the family

In a great city, where the population is unstable, where parents and

children are employed out of the house and often in distant parts of the

city, where thousands of people live side by side for years without so much

as a bowing acquaintance, these intimate relationships of the primary group

are weakened and the moral order which rested upon them is gradually

dissolved.

Under the disintegrating influences of city life most of our traditional

institutions, the church, the school, and the family, have been greatly

modified. The school, for example, has taken over some of the functions of

the family. It is around the public school and its solicitude for the moral

and physical welfare of the children that something like a new

neighbourhood and

community spirit tends to get itself organised.

The church, on the other hand, which has lost much of its influence since

the printed page has so largely taken the place of the pulpit in the

interpretation of life, seems at present to be in process of readjustment

to the new conditions.

It is important that the church, the school, and the family should be

studied from the point of view of this readjustment to the conditions of

city life.

It is probably the breaking down of local attachments and the weakening of

the restraints and inhibitions of the primary group, under the influence of

the urban environment, which are largely responsible for the increase of

vice and crime in great cities. It would be interesting in this connection

to determine by investigation how far the increase in crime keeps pace with

the increasing mobility of the population and to what extent this mobility

is a function of the growth of population. It is from this point of view

that we should seek to interpret all those statistics which register the

disintegration of the moral order, for example, the statistics of divorce,

of truancy, and of crime.

[p.43]

The moral region. - It is inevitable that individuals who seek

the same forms of excitement, whether that excitement be furnished

by a horse race or by grand opera, should find themselves from

time to time in the same places. The result of this is that in the

organisation which city life spontaneously assumes the population

tends to segregate itself, not merely in accordance with its interests,

but in accordance with its tastes or its temperaments. The resulting

distribution of the population is likely to be quite different

from that

brought about by occupational interests or

economic conditions.

Every

neighbourhood, under

the influences which tend to

distribute and

segregate city populations, may assume the character of a "moral region."

Such, for example, are the vice districts, which are found in most cities.

A moral region is not necessarily a place of abode. It may be a mere

rendezvous, a place of resort.

In order to understand the forces which in every large city tend to develop

these detached milieus in which vagrant and suppressed impulses, passions,

and ideals emancipate themselves from the dominant moral order, it is

necessary to refer to the fact or theory of

latent impulses of men.

The fact seems to be that men are brought into the world with all the

passions, instincts, and appetites, uncontrolled and undisciplined.

Civilisation, in the interests of the common welfare, demands

the suppression sometimes, and the control always, of these wild, natural

dispositions. In the process of imposing its discipline upon the

individual, in making over the individual in accordance with the accepted

community model, much is suppressed altogether, and much more finds a

vicarious expression in forms that are socially valuable, or at least

innocuous. It is at this point that sport, play, and art function. They

permit the individual to purge himself by means of symbolic expression of

these wild and suppressed impulses. This is the catharsis of which

Aristotle wrote in his Poetic, and which has been given new and more

positive significance by the investigations of

Sigmund Freud and the

psychoanalysts.

[p.44]

No doubt many other social phenomena such as strikes, wars, popular

elections, and religious revivals perform a similar

function in releasing

the

subconscious tensions. But within smaller communities, where

social

relations are more intimate and inhibitions more imperative, there are many

exceptional individuals who find within the limits of the communal activity

no normal and healthful expression of their individual aptitudes and

temperaments.

The causes which give rise to what are here described as "moral regions"

are due in part to the restrictions which urban life imposes; in part to

the license which these same conditions offer. We have, until very

recently, given much consideration to the temptations of city life, but we

have not given the same consideration to the effects of inhibitions and

suppressions of natural impulses and instincts under the changed conditions

of metropolitan life. For one thing, children, which in the country are

counted as an asset, become in the city a liability. Aside from this fact

it is very much more difficult to rear a family in the city than on the

farm. Marriage takes place later in the city, and sometimes it doesn't take

place at all.

Burgess, E.W.

1925/2

"The growth of the city:

an introduction to a research project". Chapter two in

The City (pages 47-62)

[p.50]

Expansion as a process

No study of expansion as a process has yet been made, although the

materials for such a study and intimations of different aspects of the

process are contained in city planning, zoning, and regional surveys

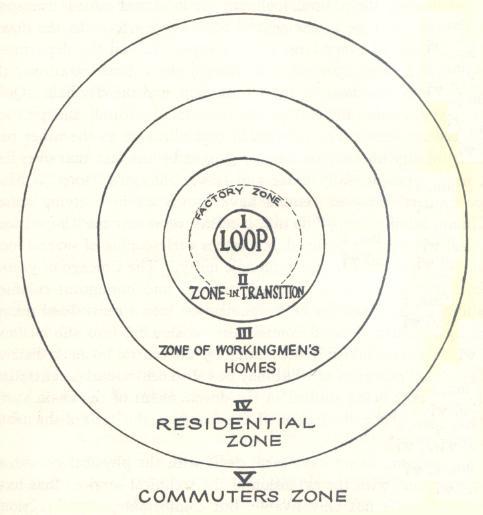

The typical processes of the expansion of the city can best be illustrated,

perhaps, by a series of concentric circles, which may be numbered to

designate both the successive

zones of urban extension and the types of

areas differentiated in the process of expansion.

This chart represents an ideal construction of the tendencies of

any town

or city to expand radially from its central business district - on the map

"The Loop"

(I).

Encircling the downtown area there is normally an area in transition, which

is being invaded by business and light manufacture

(II).

A third area

(III) is inhabited by the workers in industries who have escaped

from the

area of deterioration (II) but who desire to live within easy access of

their work.

Beyond this zone is the "residential area"

(IV)

of high-class

apartment buildings or of exclusive "restricted" districts of single family

dwellings.

Still farther, out beyond the city limits, is the commuters'

zone - suburban areas, or satellite cities-within a thirty- to sixty-minute

ride of the central business district. [V]

This chart brings out clearly

the main fact of expansion, namely, the tendency of each inner zone to

extend its area by the invasion of the next outer zone. This aspect of

expansion may be called

succession, a process which

has been studied in

detail in plant ecology. If this chart is applied to Chicago,

all four

of these zones were in its early history included in the circumference of

the inner zone, the present business district. The present boundaries

of the area of deterioration were not many years ago those of the zone now

inhabited by independent wage-earners, and within the

[p.51] memories of

thousands of Chicagoans contained the residences of the "best families."

Chart one: The Growth of the City

It hardly needs to be added that neither Chicago

[p.52] nor any other city

fits perfectly into this ideal scheme. Complications are introduced by the

lake front, the Chicago River, railroad lines, historical factors in the

location of industry, the relative degree of the resistance of communities

to invasion, etc.

Besides extension and

succession, the general process of expansion in urban

growth involves the antagonistic and yet complementary processes of

concentration and decentralisation. In all cities there is the natural

tendency for local and outside transportation to converge in the central

business district. In the down-town section of every large city we expect

to find the department stores, the skyscraper office buildings, the

railroad stations, the great hotels, the theatres, the art museum, and the

city hall. Quite naturally, almost inevitably, the

economic, cultural, and

political life centres here. The relation of centralisation to the other

processes of city life may be roughly gauged by the fact that over half a

million people daily enter and leave Chicago's "loop." More recently sub-

business centres have grown up in outlying zones. These "satellite loops"

do not, it seems, represent the "hoped for" revival of the

neighbourhood,

but rather a telescoping of several local communities into a larger

economic unity. The Chicago of yesterday, an agglomeration of country towns

and immigrant colonies, is undergoing a process of reorganisation into a

centralised decentralised system of local communities coalescing into sub-

business areas visibly or invisibly dominated by the central business

district. The actual processes of what may be called centralised

decentralisation are now being studied in the development of the chain

store, which is only one illustration of the change in the basis of the

urban organisation.1

Expansion, as we have seen, deals with the physical growth of the city, and

with the extension of the technical services that have made city life not

only livable, but comfortable, even luxurious.

[p.53]

Certain of these basic necessities of urban life are possible only

through a tremendous development of communal existence. Three millions of

people in Chicago are dependent upon one unified water system, one giant

gas company, and one huge electric light plant. Yet, like most of the other

aspects of our communal urban life, this

economic co-operation is an

example of co-operation without a shred of what the "spirit of

co-operation" is commonly thought to signify. The great public utilities

are

a part of the mechanisation of life in great cities, and have little or no

other meaning for social organisation.

Yet the processes of expansion, and especially the rate of expansion, may

be studied not only in the physical growth and business development, but

also in the consequent changes in the social organisation and in

personality types. How far is the growth of the city, in its physical and

technical aspects, matched by a natural but adequate readjustment in the

social organisation ? What, for a city, is a normal rate of expansion, a

rate of expansion with which controlled changes in the social organisation

might successfully keep pace ?

R.D. McKenzie

1925/3

"The ecological approach to the study of the human

community" Chapter three in

The City (pages 63-79)

The young sciences of

plant and

animal ecology have become fairly well established. Their

respective fields are apparently quite well defined, and a set of concepts

for analysis is becoming rather generally accepted. The subject of

human ecology, however, is still practically an unsurveyed

field, that is, so far as a systematic and scientific approach is

concerned. To be sure, hosts of studies have been made which touch the

field of human ecology in one or another of its varied aspects, but there

has developed no science of human ecology which is comparable in precision

of observation or in method of analysis with the recent sciences of plant

and animal ecology.

1. The relation of human ecology to plant and animal ecology

Ecology has been defined as

This definition is not sufficiently comprehensive to include all the

elements that logically fall within the range of human ecology. In the

absence of any precedent let us tentatively define human ecology as a study

of the

spatial and

temporal (*) relations of human beings as affected

by

the selective,

[p.64]

distributive, and

accommodative forces of the environment.

2. Ecological classification of communities

From the standpoint of ecology, communities may be divided into four

general types: first, the primary service community, such as the

agricultural town, the fishing, mining, or lumbering community...

The next type of community is the one that fulfils the secondary function

in the

distributive process of commodities. It collects the basic

materials

from the surrounding primary communities and distributes them in the wider

markets of the world. On the other hand, it redistributes the products

coming from other parts of the world to the primary service communities for

final consumption. This is commonly called the commercial community...

The third type of community is the industrial town. It serves as the locus

for the manufacturing of commodities. In addition it may combine the

functions of the primary service and the commercial types. It may have its

local trade area and it may also be the

distributing centre for the

surrounding hinterland. The type is characterized merely by the relative

dominance of industry over the other forms of service...

The fourth type of community is one which is lacking in a specific economic

base. It draws its economic sustenance from other parts of the world, and

may serve no function in the production or distribution of commodities.

Such communities are exemplified in our recreational resorts, political and

educational centres, communities of defense, penal or charitable

colonies...

3. Determining ecological factors in the growth or decline of

community

The human community tends to develop in cyclic fashion. Under a given state

of natural resources and in a given condition of the arts the community

tends to increase in size and structure until it reaches the point of

population adjustment to the

economic base. In an agricultural community,

under present conditions of production and transportation, the point of

maximum population seldom exceeds 5,000.(1)

The point of maximum development may be termed the point of culmination or

climax, to use the term of the plant ecologist. (2)

The community tends to remain in this condition of balance between

population and resources until some new element enters to disturb the

status quo, such as the introduction of a new system of communication, a

new type of industry, or a different form of utilisation of the existing

economic base. Whatever the innovation may be that disturbs the

equilibrium

of the community, there is a tendency toward a new cycle of adjustment.

This may act in either a positive or negative manner. It may serve as a

release to the community, making for another cycle of growth and

differentiation, or it may have a retractive influence, necessitating

emigration and readjustment to a more circumscribed base.

[p.70]

[p.71]

4. The effect of ecological changes on the social organisation of

community

Population migrations resulting from such sudden pulls as are the outcomes

of unusual forms of release in community growth may cause an expansion in

the community's development far beyond the natural culmination point of its

cyclic development, resulting in a crisis situation, a sudden relapse,

disorganization, or even panic. So-called "boom towns" are towns that have

experienced herd movements of population beyond the natural point of

culmination.

On the other hand, a community which has reached the point of culmination

and which has experienced no form of release is likely to settle into a

condition of stagnation. Its natural surplus of population is forced to

emigrate. This type of emigration tends to occasion folk-depletion in the

parent community. The younger and more enterprising population elements

respond most sensitively to the absence of opportunities in their home

town. This is particularly true when the community has but a single

economic base, such as agriculture, lumbering, mining. Reformers try in

vain to induce the young people to remain on the farms or in their native

villages, little realizing that they are working in opposition to the

general principles of the ecological order.

Again, when a community starts to decline in population due to a weakening

of the economic base, disorganization and social unrest follow.1

Competition becomes keener within the community, and the weaker elements

either are forced into a lower economic level or are compelled to withdraw

from the community entirely.

5. Ecological processes determining the internal structure of

community

In the process of community growth there is a development from the simple

to the complex, from the general to the specialised; first to increasing

centralisation and later to a decentralisation process. In the small town

or village the primary universal needs are satisfied by a few general

stores and a few simple institutions such as church, school, and home. As

the community increases in size specialisation takes place both in the type

of service provided and in the location of the place of service. The

sequence of development may be somewhat as follows: first the grocery

store, sometimes carrying a few of the more staple dry goods, then the

restaurant, poolroom, barber shop, drug store, dry-goods store, and later

bank, haberdashery, millinery, and other specialised lines of service.1

The axial or skeletal structure of a community is determined by the course

of the first routes of travel and traffic. 2

Houses and shops are constructed near the road, usually parallel with it.

The road may be a trail, public highway, railroad, river, or ocean harbour,

but, in any case, the community usually starts in parallel relation to the

first main highway. With the accumulation of population and utilities the

community takes form, first along one side of the highway and later on both

sides. The point of junction or crossing of two main highways, as a rule,

serves as the initial centre of the community.

As the community grows there is not merely a multiplication of houses and

roads but a process of differentiation and segregation takes place as well.

Residences and institutions spread out in centrifugal fashion from the

central point of the community, while

[p.74]

business concentrates more and more around the spot of highest land values.

Each cyclic increase of population is accompanied by greater

differentiation in both service and location. There is a struggle among

utilities for the vantage-points of position. This makes for increasing

value of land and increasing height of buildings at the geographic centre

of the community. As competition for advantageous sites becomes keener with

the growth of population, the first and economically weaker types of

utilities are forced out to less accessible and lower-priced areas. By the

time the community has reached a population of about ten or twelve

thousand, a fairly well-differentiated structure is attained. The central

part is a clearly defined business area with the bank, the drugstore, the

department store, and the hotel holding the sites of highest land value.

Industries and factories usually comprise independent formations within the

city, grouping around railroad tracks and routes of water traffic.

Residence sections become established, segregated into two or more types,

depending upon the economic and racial composition of the population.

The structural growth of community takes place in

successional sequence not

unlike the successional stages in the development of the plant formation.

Certain specialized forms of utilities and uses do not appear in the human

community until a certain stage of development has been attained, just as

the beech or pine forest is preceded by successional dominance of other

plant species. And just as in plant communities successions are the

products of invasion, so also in the human community the formations,

segregations, and associations that appear constitute the outcome of a

series of invasions.1

There are many kinds of intra-community invasions, but in general they may

be grouped into two main classes: .those resulting in change in use of

land, and those which introduce merely change in type of occupant. By the

former is meant change from one

[p.75]

general use to another, such as of a residential area into a business area

or of a business into an industrial district. The latter embraces all

changes of type within a particular use area, such as the changes which

constantly take place in the racial and economic complexion of residence

neighbourhoods, or of the type of service utility within a business

section. Invasions produce

successional stages of different qualitative

significance, that is, the economic character of the district may rise or

fall as the result of certain types of invasion. This qualitative aspect is

reflected in the fluctuations of land or rental values.

The conditions which initiate invasions are legion. The following are some

of the more important:

Invasions may be classified according to stage of development into

(b) secondary or developmental stage,

(c) climax.

The initial stage of an invasion has to do with the point of entry, the

resistance or inducement offered the invader by the prior inhabitants of

the area, the effect upon land values and rentals. The invasion, of course,

may be into an unoccupied territory or into territory with various degrees

of occupancy. The resistance to invasion depends upon the type of the

invader together with the degree of solidarity of the present occupants.

The undesirable

[p.76]

invader, whether in population type or in use form, usually makes entry

(that is, within an area already completely occupied) at the point of

greatest mobility. It is a common observation that foreign races and other

undesirable invaders, with few exceptions, take up residence near the

business centre of the community or at other points of high mobility and

low resistance. Once established they gradually push their way out along

business or transportation thoroughfares to the periphery of the community.

Park R.E.

1925/6 "Community organisation and the romantic temper"

Chapter six in

The City (pages 99-122)

...

But what is a

community and what is community organisation? Before assessing

the communal efficiency one should at least be able

[p.115]

to describe a community. The simplest possible description of a community

is this: a collection of people occupying a more or less clearly defined

area. But a community is more than that. A community is not only a

collection of people, but it is a collection of institutions. Not people,

but institutions, are final and decisive in distinguishing the community

from other social constellations.

Among the institutions of the community there will always be homes and

something more: churches, schools, playgrounds, a communal hall, a local

theater, perhaps, and, of course, business and industrial enterprises of

some sort. Communities might well be classified by the number and variety

of the institutions - cultural, political, and occupational-which they

possess. This would indicate the extent to which they were autonomous or,

conversely, the extent to which their communal functions were mediatized,

so to speak, and incorporated into the larger community.

There is always a larger community. Every single community is always a part

of some larger and more inclusive one. There are no longer any communities

wholly detached and isolated; all are interdependent economically and

politically upon one another. The ultimate community is the wide world.

a) The ecological organisation. - Within the limits of any community

the communal institutions - economic, political, and cultural - will tend

to assume a more or less clearly defined and characteristic

distribution.

For example, the community will always have a center and a circumference,

defining the position of each single community to every other. Within the

area so defined the local populations and the local institutions will tend

to group themselves in some characteristic pattern, dependent upon

geography, lines of communication, and land values. This distribution of

population and institutions we may call the ecological organisation of the

community.

Town-planning is an attempt to direct and control the ecological

organisation. Town-planning is probably not so simple as it seems.

[p.116]

Cities, even those like the city of Washington, D.C., that have been most

elaborately planned, are always getting out of hand. The actual plan of a

city is never a mere artifact, it is always quite as much a product of

nature as of design. But a plan is one factor in communal efficiency.

b) The economic organisation. - Within the limits of the ecological

organisation, so far as a free exchange of goods and services exists, there

inevitably grows up another type of community organisation based on the

division of labour. This is what we may call the occupational organisation

of the community.

The occupational organisation, like the ecological, is a product of

competition. Eventually every individual member of the community is driven,

as a result of competition with every other, to do the thing he can do

rather than the thing he would like to do. Our secret ambitions are seldom

realized in our actual occupations. The struggle to live determines finally

not only where we shall live within the limits of the community, but what

we shall do.

The number and variety of professions and occupations carried on within the

limits of a community would seem to be one measure of its competency, since

in the wider division of labour and the greater specialisation - in the

diversities of interests and tasks - and in the vast unconscious

co-operation of city life, the individual man has not only the opportunity,

but the necessity, to choose his vocation and develop his individual

talents.

Nevertheless, in the struggle to find his place in a changing world there

are enormous wastes. Vocational training is one attempt to meet the

situation; the proposed national organisation of employment is another. But

until a more rational organisation of industry has somehow been achieved,

little progress may be expected or hoped

for.

c) The cultural and political organisation. - Competition is never

unlimited in human society. Always there is custom and law which sets some

bounds and imposes some restraints upon the wild and [p.117]

wilful impulses of the individual man. The cultural and political

organisation of the community rests upon the occupational organisation,

just as the latter, in turn, grows up in, and rests upon, the ecological

organisation.

It is this final division or segment of the communal organisation with

which community-center associations are mainly concerned. Politics,

religion, and community welfare, like golf, bridge, and other forms of

recreation, are leisure-time activities, and it is the leisure time of the

community that we are seeking to organise.

Aristotle, who described man as a political animal, lived a long time ago,

and his description was more true of man then than it is today. Aristotle

lived in a world in which art, religion, and politics were the main

concerns of life, and public life was the natural vocation of every

citizen.

Under modern conditions of life, where the division of labour has gone so

far that-to cite a notorious instance-it takes 150 separate operations to

make a suit of clothes, the situation is totally different. Most of us now,

during the major portion of our waking hours, are so busy on some minute

detail of the common task that we frequently lose sight altogether of the

community in which we live.

Park R.E.

1925/7 "Magic, mentality, and city life" Chapter

seven

in

The City (pages 129-141)

During the past year two very important books have been published, in

English, dealing with the subject of

magic. The first is a translation of

Levy-Bruhl's

La Mentalite Primitive, and the other is Lynn Thorndyke's

A History of Magic and Experimental Science during the First Thirteen

Centuries of the Christian Era.

In venturing to include two volumes so different in content and point of

view in the same general category, I have justified myself

[p.124]

by adopting Thorndyke's broad definition, which includes under "magic"

Levy-Bruhl's book is an attempt, from a wide survey of

anthropological

literature, to define a mode of thought characteristic of primitive

peoples.

Thorndyke, on the other hand, is interested mainly, as the title of his

volume indicates, in the beginnings of

empirical science. The points of

view are different, but the subject-matter is the same, namely, magical

beliefs and practices, particularly in so far as they reflect and embody a

specific type of thought.

Levy-Bruhl has collected, mainly from the writings of missionaries and

travellers, an imposing number of widely scattered observations. These have

been classified and interpreted in a way that is intended to demonstrate

that the mental life and habits of thought of primitive peoples differ

fundamentally from those of

civilised man.

Thorndyke, on the other hand, has described the circumstances under which,

during the first thirteen centuries of our era, the forerunners of modern

science were gradually discarding magical practices in favour of scientific

experiment.

There is, of course, no historical connection between the

culture of Europe

in the thirteenth century and that of present-day savages, although the

magical beliefs and practices of both are surprisingly similar and in many

cases identical, a fact which is intelligible enough when we reflect that

magic is a very ancient, widespread, characteristically human phenomenon,

and that science is a very recent, exceptional, and possibly fortuitous

manifestation of social life.

Levy-Bruhl described the intelligence and habits of thought characteristic

of savage peoples as a type of mentality. The

civilised man has another and a different mentality.

"Mentality," used in this way, is an expression the precise significance of

which is not at once clear. We use the expression "psychology" in a similar

[p.125] but somewhat different way when we say, for example, that the rural

and urban populations "have a different 'psychology,'" or that such and

such a one has the "psychology" of his class-meaning that a given

individual or the group will interpret an event or respond to a situation

in a characteristic manner. But "mentality," as ordinarily used, seems to

refer to the form, rather than to the content, of thought. We frequently

speak of the type or grade of mentality of an individual, or of a group. We

would not, however, qualify the word "psychology" in any such way. We would

not, for example, speak of the grade or degree of the bourgeoise, or the

proletarian "psychology." The things are incommensurable and "psychology,"

in this sense, is a character but not a quantity.

The term "mentality," however, as Levy-Bruhl uses it, seems to include both

meanings. On the whole, however, "primitive mentality" is used here to

indicate the form in which primitive peoples are predisposed to frame their

thoughts. The ground pattern of primitive thought is, as Levy-Bruhl

expresses it, "pre-logical."

As distinguished from Europeans and from some other peoples somewhat less

sophisticated than ourselves, the primitive mind "manifests," he says, "a

decided distaste for reasoning and for what logicians call the discursive

operations of thought. This distaste for rational thought does not arise

out of any radical incapacity or any inherent defect in their

understanding," but is simply a method-one might almost say a

tradition-prevalent among savage and simple-minded people of interpreting

as wilful acts the incidents, accidents, and unsuspected changes of the

world about them.

What is this pre-logical form of thought which characterises the mentality

of primitive people? Levy-Bruhl describes it as "participation." The

primitive mind does not know things as we do, in a detached objective way.

The

uncivilised man enters, so to speak, into the world about him

and interprets plants, animals, the changing seasons, and the weather in

terms of his own impulses

[p.126]

and

conscious purposes. It is not that he is lacking in observation,

but he

has no mental patterns in which to think and describe the shifts and

changes of the external world, except those offered by the mutations of his

own inner life. His blunders of interpretation are due to what has been

described as the "pathetic fallacy," the mistake of attributing to other

persons, in this case, to physical nature and to things alive and dead, the

sentiments and the motives which they inspire in him. As his response to

anything sudden and strange is more likely to be one of fear than of any

other emotion, he interprets the strange and unfamiliar as menacing and

malicious. To the

civilised observer it seems as if the savage lived in a world

peopled with devils.

One difference between the savage and the

civilised man is that the savage is mainly concerned with

incidents and accidents, the historical, rather than scientific, aspects of

life. He is so actively engaged in warding off present evil and meeting his

immediate needs that he has neither time nor inclination to observe

routine. It is the discovery and explanation of this routine that enables

natural science to predict future consequences of present action and so

enable us to prepare today for the needs of tomorrow. It is the discovery

and explanation, in terms of cause and effect, of this routine that

constitutes, in the sense in which Levy-Bruhl uses the term, rational

thought.

What the author of primitive mentality means by "participation" is familiar

enough, though the expression itself is unusual as description of a form of

thought. Human beings may be said to know one another immediately and

intuitively by "participation." Knowledge of this kind is dependent,

however, upon the ability of human beings to enter imaginatively into one

another's minds and to interpret overt acts in terms of intentions and

purposes. What Levy-Bruhl's statement amounts to, then, is that savage

people think, as poets have always done, in terms of wills rather than

forces. The universe is a society of wilful personalities, not

[p.127]

an irrefragable chain of cause and effect. For the savage, there are

events, but neither hypotheses nor facts, since facts, in the strict sense

of the word, are results of criticism and reflection and presuppose an

amount of detachment that primitive man does not seem to possess. Because

he thinks of his world as will rather than force, primitive man seeks to

deal with it in terms of magic rather than of mechanism.

Burgess, E.W.

1925/8

"Can neighbourhood work have a scientific basis?" Chapter

eight in

The City (pages 141-155)

...

Upon reflection it is evident that markedly different social relationships

may have their roots in the conditions of a common territorial location.

Indeed, it is just these outstanding differences in communal activities,

viewed in relation to their geographic background, which have caused much

of the confusion in the use of the term "community." For community life, as

conditioned by the

distribution of individuals and institutions over an

area, has at least three quite different aspects.

First of all, there is the community viewed almost exclusively in terms of

location and movement. How far has the area itself, by its very topography

and by all its other external and physical characteristics, as railroads,

parks, types of housing, conditioned community formation and exerted a

determining influence upon the

distribution of its inhabitants and upon

their movements and life? To what extent has it had a selective effect in

sifting and sorting families over the area by occupation, nationality, and

economic or social class? To what extent is the work of neighbourhood or

community

[p.145]

institutions promoted or impeded by favorable or unfavorable location? How

far do geographical distances within or without the community symbolise

social distances? This apparently "natural" organisation of the human

community, so similar in the formation of plant and animal communities, may

be called the "ecological community."

No comprehensive study of the human community from this standpoint has yet

been made. A prospectus for such a study is outlined in an earlier chapter

by Professor R. D. McKenzie, in this volume, under the title, "The

Ecological Approach to the Study of the Human Community."1 Yet there are

several systematic treatises and a rapidly growing literature of scientific

research in the two analogous fields of plant ecology and animal ecology.

The processes of

competition, invasion,

succession, and

segregation

described in elaborate detail for plant and animal communities seem to be

strikingly similar to the operation of these same processes in the human

community. The assertion might even be defended that the student of

community life or the community organisation worker might secure at present

a more adequate understanding of the basic factors in the natural

organisation of the community from Warming's

Oecology of Plants or from

Adams's

Guide to the Study of Animal Ecology than from any other

source.

In the second place, the community may be conceived in terms of the effects

of communal life in a given area upon the formation or the maintenance of a

local culture. Local culture includes those sentiments, forms of conduct,

attachments, and ceremonies which are characteristic of a locality, which

have either originated in the area or have become identified with it. This

aspect of local life may be called "the cultural community."

The immigrant colony in an American city possesses a culture unmistakably

not indigenous but transplanted from the Old World. The telling fact,

however, is not that the immigrant colony maintains its old-world cultural

organisation, but that in its new environment it mediates a cultural

adjustment to its new situation.

How basically culture is dependent upon

place is suggested by the following expressions, "New England conscience,"

"southern hospitality," "Scottish thrift," "Kansas is not a geographical

location so much as a state of mind."

Neighbourhood institutions like the

church, the school, and the settlement are essentially cultural

institutions...

There remains a third standpoint from which the relation of a local area to

group life may be stated. In what ways and to what extent does the fact of

common residence in a locality compel or invite its inhabitants to act

together? Is there, or may there be developed upon a geographical basis, a

community consciousness? Does contiguity by residence insure or predispose

to co-operation in at least those conditions of life inherent in geographic

location, as transportation, water supply, playgrounds, etc.? Finally, what

degree of social and political action can be secured on the basis of local

areas? This is the community of the community organisation worker and of

the politician, and may be described as "the political community." It is

upon this concept of the community as a local area that American political

organisation has been founded.

These three definitions of the community are not perhaps altogether

mutually exclusive. They do, however, represent three distinctly different

aspects of community life that will have to be

[p.147]

recognised in any basic study of the community and of community

organisation. A given local area, like Hyde Park in Chicago, may at the

same time constitute an ecological, cultural, and political community,

while another area like the lower North Side in the same city, which forms

a distinct ecological unit, falls apart into several cultural communities

and cannot, at any rate from the standpoint of a common and effective

public opinion, be said to constitute a going political community. The

Black Belt in Chicago comprises one cultural community but overflows

several ecological areas and has no means of common political action except

through ward lines arbitrarily drawn.

It follows that the boundaries of local areas determined ecologically,

culturally, and politically seldom, if ever, exactly coincide. In fact, for

American cities it is generally true that political boundaries are drawn

most arbitrarily, without regard either to ecological or cultural lines, as

is notoriously the case in the familiar instance of the gerrymander.

Therefore it is fair to raise the question: How far are the deficiencies in

political action through our governmental bodies and welfare action through

our social agencies the result of the failure to base administrative

districts upon ecological or cultural communities?

This analysis of the community into its threefold aspects suggests that the

study of social forces in a local area should assume that the neighbourhood

or the community is the resultant of three main types of determining

influences: first, ecological forces; second, cultural forces; and third,

political forces.

Wirth, L.

1925/10

"A Bibliography of the Urban Community" Chapter ten

in

The City (pages 161-228)

[p.160]

The city... may be regarded as the product of three fundamental

processes: the

ecological, the

economic, and the

cultural, which operate

in the urban area to produce groupings and behaviour which distinguish

that area from its rural periphery.

[p.187]

V. The ecological organisation of the city

Just as the city as a whole is influenced in its position,

function, and

growth by

competitive factors which are not the result of the design of

anyone, so the city has an internal

organisation

which may be termed an

ecological organisation, by which we mean the

spatial

distribution of

population and institutions and the

temporal

sequence of

structure and

function following from the operation of selective, distributive, and

competitive forces tending to produce typical results wherever they are at

work. Every city tends to take on a structural and functional pattern

determined by the ecological factors that are operative.

1. Plant ecologists have been accustomed to use the expression

"natural area"

to refer to well-defined

spatial units having their own peculiar

characteristics. In human ecology the term "natural area" is just as

applicable to groupings according to selective and cultural

characteristics. Land values are an important index to the boundaries of

these local areas. Streets, rivers, railroad properties, street-car lines,

and other distinctive marks or barriers tend to serve as dividing lines

between the natural areas within the city.

2. The

neighbourhood

is typically the product of the village and the small

town. Its distinguishing characteristics are close proximity, co-operation,

intimate social contact, and strong feeling of social consciousness. While

in the modern city we still find people living in close physical proximity

to each other, there is neither close co-operation nor intimate contact,

acquaintanceship, and group consciousness accompanying this spatial

nearness. The neighbourhood has come to mean a small, homogeneous

geographic section of the city, rather than a self-sufficing, co-operative,

and self-conscious group of the population.

[p.191]

3. The local

community and the

neighbourhood in a simple form of

society

society

are

synonymous terms. In the city, however, where specialisation has

gone

very far, the grouping of the population is more nearly by occupation and

income than by kinship or common tradition. Nevertheless, in the large

American city, in particular, we find many local communities made up of

immigrant groups which retain a more or less strong sense of unity,

expressing itself in close proximity and, what is more important, in

separate and common social institutions and highly effective communal

control. These communities may live in relative isolation from each other

or from the native communities. The location of these communities is

determined by competition, which can finally be expressed in terms of land

values and rentals. But these immigrant communities, too, are in a constant

process of change, as the economic condition of the inhabitants changes or

as the areas in which they are located change.

[p.192]

4. The city may be graphically depicted in terms of a series of concentric

circles, representing the

different zones or typical areas

[p.193] of settlement. At the canter we find the business district, where

land values are high. Surrounding this there is an area of deterioration,

where the slums tend to locate themselves. Then follows an area of

workmen's homes, followed in turn by the middle-class apartment section,

and finally by the upper-class residential area. Land values, general

appearance, and function divide.these areas off from each other. These

differences in structure and use get themselves incorporated in law in the

form of zoning ordnances. This is an attempt, in the face of the growth of

the city, to control the ecological forces that are at work.

5. The needs of communal life impose upon the city a certain degree of

order which sometimes expresses itself in a city plan which is an attempt

to predict and to guide the physical structure of the city. The older

European cities appear more like haphazard,

[p.194]