Social Science History

Biographical Literature Reviews

Being written by Social Science History students at Middlesex University

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z| Aquinas - books and articles | Aquinas - weblinks |

Thomas Aquinas was a theologian and philosopher writing in the thirteenth century. Unlike Comte, who saw theological thinking as a necessary step to science, but a hindrance in an attempt to gain real understanding, Aquinas believed that it was through theology that real truth could be found. He even refers to his work as a science.

Aquinas was ordained a priest around 1250 and began teaching at the university of Paris a few years later. His first writings were summaries of lectures that he gave during this time. In his first major work, he wrote commentaries on the work of an Italian theologian, Peter Lombard, a man who can be considered a great influential character for Aquinas.

Aquinas was also greatly influenced by both the work of Aristotle and by Roman Catholic doctrine and was the first to develop a synthesis of these. While it had previously been thought that their views were at opposition to one another, Aquinas attempted to show that they are fully compatible. In his most famous work, the Summa Theologica, he scientifically arranges an exposition of this, showing how he thinks theology and philosophy are related.

Unlike Comte, who saw theological thinking as a hindrance in an attempt to gain real understanding, Aquinas believed that it was through theology that real truth could be found. For him, theology really was wisdom. He even refers to his work as a science. We can immediately see by this, a direct contrast to the views of Comte on theology's worth. Aquinas believed theology to be a science because he saw it proceeding from principles that are certain.

"Sacred doctrine is a science...because it proceeds from principles established by the light of a higher science, namely, the science of God." (Summa Theologica, Part 1, Question 1, Answer 2)

Before Aquinas, western thought had been dominated by the idea that in search for truth, people must depend on sense experience, and it was widely believed that philosophy was independent of revelation. Writing in the thirteenth century, Aquinas was influenced largely by the work of Aristotle and spent a great deal of time attempting to produce a synthesis of his work and Christian doctrine. At the time of Aquinas' writing, the Averroist theory of double truth was prominent. It was widely believed that philosophical and theological truths could not be related. Reason and revelation were considered at opposition to one another. Aquinas, however, did not accept this idea.

Aquinas believed that there could only be one truth. He saw, however, that there are two ways of knowing truth: many things are accessible to natural reason but there are some things which can only be known about God by faith in what has been revealed to us. Russell, however, criticises Aquinas by saying that before he begins to philosophise, he already knows the 'truth' as the answers lie in the Catholic faith.

Aquinas, however, does see certain cases in which both revelation and rational demonstration can be used to find truth. The existence of God and the immortality of the soul are examples of these. He believed that God revealed these truths to make them accessible to people who did not have a philosophical mind.

"It was necessary that man should be taught by a divine revelation; because the truth about God such as reason could discover, would only be known by a few, and that after a long time and with the admixture of many errors_It was therefore necessary that besides philosophical science built up by reason, there should be a sacred science learned through revelation." ( (Summa Theologica, Part 1. Question 1. Answer 1)

For those that did have a philosophical mind, Aquinas believed that using rational reasoning, he could demonstrate that God exists. He produced five famous proofs for the existence of God in part one, question one, answer three of the his Summa Theologica. The first of these is the argument of the unmoved mover, the second is the argument of the First Cause and the third is that there must be an ultimate cause of all necessity. These first three arguments are very similar and could be criticised for actually being the same argument, and so, in fact, offer only one proof. The fourth proof states that because there are perfections in the world, they must be the source of something perfect. The fifth proof argues that things must have a purpose.

Aquinas' belief that he could use rational reasoning as well as revelation to prove the existence of God, suggests that he did not see philosophy and theology as being opposed as was commonly thought. He actually believed them to be related, although distinct. He saw them being related in the sense that by demonstrating the existence of God and the immortality of the soul, philosophy shows that faith is necessary. Theology helps philosophy to reflect more deeply and correct itself if a philosophical conclusion is contrary to the mysteries of faith. ( (Summa Theologica, Part 1, Question 1. Answer 1 - Queston 12 Answer 4 - Question 32, Answer 1). Aquinas saw that nothing in revelation is contrary to reason.

"Whatsoever is found in other sciences contrary to any truth of this science must be condemned as false." (Summa Theologica Part 1, Question 1, Answer 6)

It seems evident then, that for Aquinas, it is in theology that real truth is found. Unlike Comte, who believed that theological thinking would not lead to knowledge and understanding, Aquinas held the belief that theology was in fact wisdom.

"Sacred doctrine is especially called wisdom." (Summa Theologica Part 1. Question 1. Answer 6)

He believed that a wise person would consider the end of the universe. This is because he believed that things get their end from their maker and so considering its end will mean considering its source. The wise person that does this will not consider just one area of truth as the various sciences do, but that truth which is the source of all truth.

"He who considers absolutely the highest cause of the whole universe, namely God, is most of all called wise." (Summa Theologica Part 1, Question 1, Answer 6)

This was important for Aquinas as he held the ancient concept of wisdom; that a good ruler would need to be a wise man so that he knew how to order and direct things. This real wisdom, which can be obtained by rational reasoning and revelation, was, for Aquinas, different to mere science as we require wisdom to use our scientific knowledge. In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas states his belief that,

"Other sciences consider only those things which are within reason's grasp." (Summa Theologica Part 1. Question 1. Answer 5)

One could infer, a belief that theology, for Aquinas, far from being inferior, is 'above' the other sciences as it goes beyond considering things which only reason can obtain knowledge of. It is evident that, for Aquinas, theology is the highest form of wisdom.

"the slenderest knowledge that may be obtained of the highest things is more desirable than the most certain knowledge obtained of lesser things." (Summa Theologica Part 1, Question 1. Answer 5)

For Aquinas then, it is through theology, rather than any other science that we can obtain real truth.

In comparing this idea to the ideas of Comte, we see a distinct difference. While Aquinas holds the idea that rational reasoning and considering questions about the universe and its source will provide us with truth, Comte sees that only positive thinking can do this and that thinking theologically is a vain search after absolute notions. Our thought needs to evolve into the positive stage of thinking where observation will help us to gain real knowledge.

Aquinas, unlike many other philosophers, maintains that we can know objects as they are in reality outside of ourselves. He believed that we can know things in two ways: as they exist in themselves and as they exist in thought. He states,

"the intelligible species, is the form by which the intellect understands. But since the intellect reflects upon itself, by such reflection it understands both its own act of intelligence, and the species by which it understands. Thus the intelligible species is that which is understood secondarily; but that which is primarily understood is the object of which the species is the likeness." (Summa Theologica Part 1. Question 85. Answer 2)

It seems clear then, that contrary to the views of other philosophers such as Locke, for example, who believed that we do not know things in themselves, only our ideas of them, Aquinas thought that our ideas are the way by which we know things and not merely all that we know. For him,

"the soul knows external things by means of its intelligible species." (Summa Theologica Part 1. Question 85. Answer 2)

| Aristotle - books and articles | Aristotle - weblinks |

| Beccaria - books and articles | Beccaria - weblinks |

Life and works

Beccaria was an Italian born in Milan. In 1713 the rule of Milan had passed from the Spanish to the Austrians. The rule of Empress Maria Teresa of Austria (1740-1780) and her son and successor Joseph 2nd of Austria (1780- 1790) gave rise to a long period of reform and cultural and economic reawakening. Beccaria's On Crime and Punishment) (1764) has been described as the high point of the Milan enlightenment and Il Caffè, the journal he wrote for between 1764 and 1766, as the reference point of Italian enlightenment reforms. (il punto di riferimento del riformismo illuministico italiano).

15.3.1738 Cesare Beccaria born into an aristocratic family in Milan Italy.

1746 At the age of eight Beccaria was sent to Parma to receive a Jesuit education. He displayed a talent and liking for Mathematics.

1748 Montesquieu The Spirit of the Laws "Law in general is human reason, inasmuch as it governs all the inhabitants of the earth: the political and civil laws of each nation ought to be only the particular cases in which human reason is applied."

The Italian Wikipedia says that Beccaria was influenced by Locke, Helvetius, Rousseau and Condillac.

1758 Beccaria received a degree in law from the University of Pavia.

Beccaria's period in prison Claudia writes that Beccaria's father

had him imprisoned to prevent him marrying Teresa Blasco, who was poor.

He released thanks to a grace/mercy by Maria Theresa of Austria and

reconciled to his father two years later with the help of

Pietro Verri. She says

1761 Beccaria married 17 year old Teresa Blasco

L'Accademia dei Pugni (Academy of the Fists), also called Società

dei Pugni (Society of the Fists) founded in Milan

in 1761 by

Pietro and

Allesandro Verri.

A cultural club with vigorous

debates around enlightenment topics. Beccaria was an active member. The

Academy founded the review

Il Caffè

, whose suspension in

1766 marked the end of the activities of the

Academy. (See

Italian Wikipedia)

1762 A daughter, first of Beccaria's three children born.

"The study of

Montesquieu seems to have directed his attention towards

economic questions; and his first publication (1762) was a tract on the

derangement of the currency in the Milanese states, with a proposal for its

remedy"

(1911 Encyclopedia)

Beccaria published

Del disordine e de' rimedii delle monete nello Stato di Milano nell'anno

1762 (On Remedies for the Monetary Disorders of Milan in the Year 1762

"Shortly after, in conjunction with his friends the

Verris, he formed a

literary society, and began to publish a small journal, in imitation of the

Spectator, called Il Caffè" [The Coffee House].

(1911 Encyclopedia)

Il Caffè was published from June 1764 to May 1766. 53 of its

signed articles are by Pietro Verri, 31 by Alessandro Verri and 7 by Cesare

Beccaria. 27 articles were signed by other people.

Italian Wikipedia

1764 Beccaria's great work Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crime

and

Punishment) published, anonymously at first. In this he argued that law is

based on a

social contract between the members of society, that

crime was the natural result of every individual wanting to get

away with breaking the contract, and that

punishment should be to deter people from

harming society, He argued that punishments should be

certain and infallible, not vicious or

intense, and in

proportion with the crimes committed. Justice should be

public and punishment should

teach people not to commit crimes.

Very quickly translated into French by André Morellet (1727-1819)

in 1765, German in 1766, into English anonymously from the

French in 1767, Swedish in 1770, Polish in 1772 and

Spanish in 1774,

(French Wikipedia)

1766 Beccaria went to Paris with

Alessandro Verri. Beccaria returned after only a month, but

Alessandro remained and went on to England. In Paris, Beccaria moved in the

circle of the

Encyclopedist Baron d' Holbach

End of

Il Caffè

1767 An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, translated from the

Italian; with a commentary, attributed to Monsieur de Voltaire, translated

from the French. London : J. Almon, 1767.

Jeremy Bentham's

early manuscripts

mention Beccaria.

In November 1768, Beccaria was . His lectures on political economy

November 1768 Beccaria appointed to the chair of law and economy

founded expressly for him at the Palatine college of Milan. After his death

his lectures Elementi

di economia pubblica ("Elements of Public Economy") were published in

1804.

1771 Beccaria appointed to the Supreme Economic Council of Milan

(Austria ?) and remained a public official for the remainder of his life.

"Entered the Austrian administration and a member of the Supreme Council of

the Economy ... contributing to the Hasburg reforms."

Italian Wikipedia

1776 Austria outlawed witch burnings and torture and took capital

punishment off the penal code, as it was replaced with forced labor.

Capital punishment was later reintroduced.

(Wikipedia)

1776 Britain

Jeremy Bentham's

A Fragment of Government

29.11.1780 Joseph (Giuseppe) 2nd succeeded Maria Teresa to the

throne of Austria and

the places in power for the Milan reformists were reduced. [I think this is

because Joseph centralised power. He was a reform emperor]

Wikipedia says he "inspired a complete reform

of the legal system, abolished brutal punishments and the death penalty in

most instances, and imposed the principle of complete equality of treatment

for all offenders. He ended censorship of the press and theatre"

1784 Joseph (Giuseppe) ordered that the whole of the Holy

Roman

Empire

change its language of instruction and administration from Latin to German,

(See

Votruba, M. 2010?)

May 1789 Start of the

French Revolution

1789

Jeremy Bentham's

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and

Legislation

26.8.1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

1791 Beccaria appointed to the board for the reform of the judicial

code. (Wikipedia)

1791 French Penal

Code

28.11.1794 Beccaria died of a stroke in Milan

Crimes and punishments

Social contract - The pact at the base of society

Punishment and the aim of punishment

Social contract - The pact at the base of society

The whole Beccaria's discourse starts from the essential distinction

between natural laws and laws that come from the pact, or contract, at the

base of a society. He argues that it is the lack of this distinction which

allows tyrants to have the power to do everything they want to their

subjects, claiming even the right to decide about their life. This happens

because they demand to personify not only the will of the people, but also

the God's one.

Therefore Beccaria reminds us that society is grounded on a pact between

the people who belong to the society, in order to protect each other. This

pact is composed from laws that are

Morover:

The two above utterances allow Becaria to explain what punishment is. I

will return to this when I have examined what Beccaria says about crime.

Crime

Punishment and the aim of punishment

The two earlier utterances allow Beccria to state that:

Punishments are:

Therefore punishments become necessary to defend society, functioning as

deterrent to commit crimes, that are all actions contrary to the public

good (le azioni opposte al bene pubblico). (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 6)

The aim of punishments is:

An eloquent example of the latter utterance can be found in the chapter

concerning the punishment of death.

Beccaria with consistent and logical thought explains that the capital

punishment is not only unjust

(Did any one ever give to others the right of taking away his life?,

(Chi è mai colui che

abbia voluto lasciare ad

altri uomini l'arbitrio di ucciderlo?) (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 28 -)

but even useless as deterrent for two reasons:

1. People tend to forget cruel and intense events:

2 The moment of death is just a moment and it is not very much compared to

all those days of happiness that a crime could give to the criminal:

Characteristics of Punishment

Therefore now it can be examined the characteristics of punishments.

Punishments have to be certain and infallible, not vicious or

intense:

Beccaria talks about the examples of impunity, referring to the fact that

an accused man has not to be considered criminal, as long as his guilt has

not been proved. One of the most popular way to get the confession of an

assumed criminal, was the torture.

Beccaria points out as this way to reach the truth is useless for such aim,

and advantageous only to criminals, and always unjust to innocents. As a

matter of fact, it may happens that a criminal has the opportunity to be

absolved thanks to his strength to resist pain, but a weak innocent would

confess everything to stop pain and so will be condemned, just for his

weakness to resist pain.

Therefore torture is advantageous to criminals and disadvantageous to

innocents:

Punishments need a proportion with the crimes committed. Crimes with

different intensity must be associated with different punishments.

It is from this principle of the proportion between crimes and punishments

that Beccaria suggests a scale of crime, with concerning punishments.

Therefore he points out that is counterproductive to assign the same

punishment to two different crimes, with different intensity. The

consequence of this it would be that people feel allowed to commit the

worse crime if it would bring grater advantage:

Punishments must be public, and also the judgement, thus it can become a

valuable deterrent:

Moreover, the time that has to elapse between the crime and the punishment

must be the most short as possible, thus people can more easily associate

the crime and the relative punishment.

"An example about how prisons were used in Beccaria's time, is

offered by his own experience. Beccaria's father used prisons to imprison

him in order to prevent his son from marrying a woman belonging to a lower

class. This was possible for the right of patria potestas which was still

in force among nobles in that time. This right, in force from Romans,

stated that the

pater familias, the patriarch, had a total authority and every

right on the members of the family, even that of death, in order to

preserve the patrimony of the family. Therefore, appealing to this right in

order to avoid a marriage which could ruin the family patrimony, Beccaria's

father could put him in prison"

"After the passage of three years, all the imperial courts of

justice and local courts shall handle all their respective cases in German

at their locations, and the lawyers themselves shall prepare all their

cases in this language and present them to the courts. Nevertheless,

His Majesty is not unwilling to extend this deadline according to

identified circumstances, which the imperial offices will be able to

advance in their time. The statutes will remain in Latin, because the

lawyers and judges must, regardless, know this language, which is part of

academic scholarship"

Punishments have to be certain and infallible, not vicious or

intense:

"importantissimo di separare ciò che risulta da questa

convenzione, cioè dagli espressi o taciti patti degli uomini,

perché tale è il limite di quella forza che può

legittimamente esercitarsi tra uomo e uomo senza una speciale missione

dell'Essere supremo."

"Most important is to separate what is the result of this

convention, that is from the explicit or tacit pacts between men, because

such is the limit of that power which can be justifiably exerted between

man and man without a special mission of the Supreme Being"

"le condizioni, colle quali uomini indipendenti ed isolati si

unirono in società, stanchi di vivere in un continuo stato di

guerra e di godere una libertà resa inutile dall'incertezza di

conservarla. Essi ne sacrificarono una parte per goderne il restante con

sicurezza e tranquillità. La somma di tutte queste porzioni di

libertà sacrificate al bene di ciascheduno forma la sovranità

di una nazione, ed il sovrano è il legittimo depositario ed

amministratore di quelle;" (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 1)

"the conditions under which men, naturally independent, united

themselves in society. Weary of living in a continual state of war, and of

enjoying a liberty which became of little value, from the uncertainty of

its duration, they sacrificed one part of it, to enjoy the rest in peace

and security. The sum of all these portions of the liberty of each

individual constituted the sovereignty of a nation and was deposited in the

hands of the sovereign, as the lawful administrator."

"L'aggregato

di queste minime porzioni possibili forma il diritto di punire; tutto il di

pií è abuso e non giustizia, è fatto, ma non

già diritto." (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 2)

"The aggregate of these, the smallest portions possible, forms

the right of punishing; all that extends beyond this, is abuse, not

justice."

"No man ever gave up his liberty merely for the good of the

public. Such a chimera exists only in romances. Every individual wishes, if

possible, to be exempt from the compacts that bind the rest of mankind"

(Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 2)

"motivi sensibili

che bastassero a distogliere il dispotico animo di ciascun uomo dal

risommergere nell'antico caos le leggi della società." (Beccaria

1764 - Chapter 1)

"some motives therefore, that strike the senses were necessary

to prevent the despotism of each individual from plunging society into its

former chaos."

"impedire il reo dal far nuovi danni ai suoi

cittadini e di rimuovere gli altri dal farne uguali." (Beccaria 1764 -

Chapter 12 -)

"no other than to prevent the criminal from doing further

injury to society, and to prevent others from committing the like

offence."

"Parmi un assurdo che le leggi, che sono l'espressione della

pubblica volontà, che detestano e puniscono l'omicidio, ne

commettono uno esse medesime, e, per allontanare i cittadini

dall'assassinio, ordinino un pubblico assassinio." (Beccaria 1764 -

Chapter 28 -)

"Is it not absurd, that the laws, which detest and punish

homicide, should, in order to prevent murder, publicly commit murder

themselves?"

"Non è l'intensione della pena che fa il maggior effetto

sull'animo

umano, ma l'estensione

di essa; perché la nostra sensibilità è pií

facilmente e stabilmente mossa

da minime ma replicate impressioni che da un forte ma passeggiero

movimento." (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 28 -)

"It is not the intenseness of the pain that has the greatest

effect on the mind, but its continuance; for our sensibility is more easily

and more powerfully affected by weak but repeated impressions, than by a

violent but momentary impulse."

"Perché una pena ottenga il suo effetto basta che il

male della pena ecceda il bene che nasce dal delitto, e in questo eccesso

di male dev'essere calcolata l'infallibilità della pena e la perdita

del bene che il delitto produrrebbe. (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter

27)"

"That a punishment may produce the effect required, it is

sufficient that the evil it occasions should exceed the good expected from

the crime, including in the calculation the certainty of the punishment,

and the privation of the expected advantage."

"Uno dei pií gran freni dei delitti non è

la crudeltà delle pene,

ma l'infallibilità di esse... la certezza di un castigo,

benché moderato, farà sempre una maggiore impressione che non

il timore di un altro pií terribile, unito colla speranza

dell'impunità;" (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 27)

"The certainty of a small punishment will make a stronger

impression than the fear of one more severe, if attended with the hopes of

escaping; for it is the nature of mankind to be terrified at the approach

of the smallest inevitable evil, whilst hope, the best gift of Heaven hath

the power of dispelling the apprehension of a greater, especially if

supported by examples of impunity, which weakness or avarice too frequently

afford."

"Questo è il mezzo sicuro di assolvere i robusti

scellerati e di condannare i deboli innocenti." (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter

16)

"By this method the robust will escape, and the feeble be

condemned."

"il reo ha un caso favorevole per sé, cioè

quando, resistendo alla

tortura con fermezza, deve essere assoluto come innocente; ha cambiato una

pena maggiore in

una minore. Dunque l'innocente non può che perdere e il colpevole

può guadagnare." (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 16)

"A very strange but necessary consequence of the use of torture

is, that the case of the innocent is worse than that of the guilty. With

regard to the first, either he confesses the crime which he has not

committed, and is condemned, or he is acquitted, and has suffered a

punishment he did not deserve. On the contrary, the person who is really

guilty has the most favourable side of the question; for, if he supports

the torture with firmness and resolution, he is acquitted, and has gained,

having exchanged a greater punishment for a less."

"Non solamente è interesse comune che non si commettano

delitti, ma

che siano pií rari

a proporzione del male che arrecano alla società. Dunque pií

forti debbono essere gli

ostacoli che risospingono gli uomini dai delitti a misura che sono contrari

al ben pubblico, ed

a misura delle spinte che gli portano ai delitti. Dunque vi deve essere una

proporzione fra i delitti

e le pene." (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 6 -)

"It is not only the common interest of mankind that crimes

should not be committed, but that crimes of every kind should be less

frequent, in proportion to the evil they produce to society. Therefore the

means made use of by the legislature to prevent crimes should be more

powerful in proportion as they are destructive of the public safety and

happiness, and as the inducements to commit them are stronger. Therefore

there ought to be a fixed proportion between crimes and

punishments."

"Se una

pena uguale è destinata a due delitti che disugualmente offendono la

società, gli

uomini non troveranno un pií forte ostacolo per commettere il

maggior delitto, se con esso vi

trovino unito un maggior vantaggio." (Beccaria 1764 - Chapter

6)

"If an equal punishment be ordained for two crimes that injure

society in different degrees, there is nothing to deter men from committing

the greater as often as it is attended with greater advantage."

"Pubblici

siano i giudizi, e pubbliche le prove del reato, perché l'opinione,

che è forse il

solo cemento delle società, imponga un freno alla forza ed alle

passioni, perché

il popolo dica noi non siamo schiavi e siamo difesi, sentimento che inspira

coraggio e che

equivale ad un tributo per un sovrano che intende i suoi veri interessi."

(Beccaria 1764 - Chapter 14)

"All trials should be public, that opinion, which is the best,

or perhaps the only cement of society, may curb the authority of the

powerful, and the passions of the judge, and that the people may say, "We

are protected by the laws; we are not slaves"; a sentiment which inspires

courage, and which is the best tribute to a sovereign who knows his real

interest."

"Egli è dunque di somma importanza la vicinanza del

delitto e della pena, se si vuole che nelle rozze menti volgari, alla

seducente pittura di un tal delitto vantaggioso, immediatamente

riscuotasi l'idea associata della pena. Il lungo ritardo non produce altro

effetto che di sempre pií disgiungere queste due ide" (Beccaria 1764

- Chapter 19)

"It is, then, of the. greatest importance that the punishment

should succeed the crime as immediately as possible, if we intend that, in

the rude minds of the multitude, the seducing picture of the advantage

arising from the crime should instantly awake the attendant idea of

punishment. Delaying the punishment serves only to separate these two

ideas, and thus affects the minds of the spectators rather as being a

terrible sight than the necessary consequence of a crime, the horror of

which should contribute to heighten the idea of the

punishment."

| Bentham - books and articles |

Bentham - weblinks

See crime timeline |

Biography related to Bentham's relevant ideas, activities and writing

15.2.1748 Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was born in London to an affluent Tory family. His father was a prominent and prosperous attorney (solicitor).

Bentham studied Latin from the age of three

Bentham went to Queens College Oxford when he was only twelve.

At Queen's, Bentham took his Bachelor's degree

(aged 15) in

1763 and his Masters in 1766.

1763 Entered at

Lincoln's Inn, and took his seat as a student in the Queen's

Bench

From 1765 Jeremy Bentham had a small private income

1768: Jeremy Bentham sees the light:

At twenty he had decided his vocation: he would provide a foundation for

scientific jurisprudence and legislation

(Harrison, W. 1967, p.vii)

In 1768 Jeremy Bentham discovered the principle of utility, that the

greatest happiness of the greatest number is the only proper measure of

right and wrong and the only proper end of government

(Steintrager, J.

1977 p.11 first sentence of book)

Footnote 3: Precisely from whom Bentham first

learned the principle of utility is not clear. In later years he attributed

the discovery to a chance reading of a pamphlet by Joseph Priestly, but the

early manuscripts frequently mention Helvetius and even

Beccaria.

(Steintrager, J.

1977 p.18)

|

Bentham

wrote about law rather than practising it. He was interested in the theory

of law so he dedicated most of his life to writing on matters of legal

reform.

The website of the Bentham Project says Bentham

"became disillusioned with the law, especially after hearing the lectures of the leading authority of the day, Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780)" Blackstone had lectured on law at Oxford since 1753. In 1756 he published his An Analysis of the Laws of England - His own version of his lectures at Oxford. William Blackstone argued that English law embodies the collective wisdom of the society.

Between 1765 and 1769, Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England were published. |

1772

1775 Bentham's manuscripts from which

Dumont extracted "La Théorie

des Peines"

1776:

In

A Fragment on Government - Being an examination of what is

delivered, on the subject of government in general in the introduction to

Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries: by Jeremy Bentham with a Preface, in

which is given a critique on the work at large (Bentham, J. 1776), Bentham

criticised a

passage in Blackstone's

Commentaries on the Laws of England.

He described Blackstone's idea that English law embodies the

collective

wisdom of the society as a "fiction" - a set of ideas hiding

the true

motives of those who proclaim them.

Bentham's scientific study of law was to be based on

the understanding that humans pursue happiness and avoid pain.

This key to

all human behaviour was later called

utilitarianism.

By 1780, Bentham he had finished his Introduction to the

Principles of

Morals and

Legislation, which was not published until

1789. He asked himself if he

had

a genius for anything, and replied that he had a genius for legislation "I

am going to be the Newton of morals and legislation". (John Annette)

From 1785 to 1788, Bentham travelled the

Continent, including

Russia. It

was here that he developed his idea of a model institution:

the "Panopticon".

He developed the idea in a series of

letters

from Russia

to a friend in England, in 1787.

These were published in 1791 as

Panopticon; or, the Inspection-House: Containing the Idea

of a New

Principle of Construction Applicable to Any Sort of

Establishment, in which Persons of Any Description Are to Be

Kept Under

Inspection

(Bentham, J. 1791)

1787 Jeremy Bentham circulates a plan for a Panopticon or model

prison

1787 Jeremy Bentham's Defence of Usuary published (written in

Russia)

1788

Jeremy Bentham returned to England with his plan for a model prison or

Panopticon

Through Samuel Romilly, Jeremy Bentham met

Étienne Dumont, a Swiss

exile who undertook the revision and French translation of parts of his

manuscripts; publication in France began in the same year in Mirabeau's

Courrier de Provence. The fundamental ideas and most of the

illustrative material came from Bentham's manuscripts. Dumont sought to

re-write in a shorter and clearer form suitable for the ordinary reading

public. As well as deleting repetitive matter, he filled in gaps in the

argument.

In 1789 Jeremy Bentham published

An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and

Legislation

(Bentham, J. 1789). This was based on the principle of utility:

That all human

behaviour is based on the desire for pleasure and the fear of pain. Any

rule should increase pleasure and decrease pain. The state in making law

should promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number. (John

Annette)

May 1789 Start of the

French Revolution

26.8.1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

1791

Jeremy Bentham published Panopticon; or, the Inspection-House: Containing

the Idea of a New Principle of Construction Applicable to Any Sort of

Establishment, in which Persons of Any Description Are to Be Kept Under

Inspection. Dublin [H+M p.446]

Jeremy Bentham published Essay on Political Tactics

1791 French Penal

Code

1792 Jeremy Bentham made an honorary citizen of the

French Republic.

1793 Jeremy Bentham published Emancipate your Colonies

October 1793 to February 1794: Jeremy Bentham drafting a

prison bill.

1794: Penitentiary Bill

1794: Parliament accepted the Panopticon scheme

In 1794 the British Parliament backed Bentham's

Panopticon as the

plan

for a new prison. Bentham was to run it under contract.

Foundations were

laid, but in January 1803, Bentham was told the

government could not

find

the funds to complete it.

28.11.1794

Beccaria died in Milan

Bentham, J. and

Dumont, P. 1802 Traité de legislation

civile et pénale

Bentham, J. and

Dumont

P. 1811

Théorie des peines et des recompenses. Translated into

English as The Rationale of Punishment by Richard Smith in 1830

Bentham, J. and

Dumont, P. 1815

Tactique des assemblées legislatives

About 1820

John Stuart Mill was

converted to Benthamism as a "philosophy of life". He saw the "greatest

happiness of the greatest number" principle as the tool for reforming all

laws and institutions.

Summer 1821

John Stuart Mill went to

France as a guest of Samuel Bentham. He stayed 12 months. On the way

through Paris stayed with M. Say and met

Saint Simon.

July 1822 See Bentham's note on the

greatest happiness or greatest felicity principle

Winter 1822/1823

John Stuart Mill formed the

Utilitarian Society (broken up in 1826). This met in Bentham's house. The

members who became intimate companions were: William Eyton Tooke, William

Ellis, George Graham and (from 1824) George Arthur Roebuck.

Bentham, J. and

Dumont,

P. 1823 Traité des preuves

judiciaires

Bentham, J. and

Dumont, P. 1828

De l'organization judiciaire et de la codification

Bentham, J. 1830 History of the War Between Jeremy

Bentham

and George

3rd, By One of the Belligerents.

6.6.1832 Bentham died in London

Utilitarianism

I will begin with Bentham as I want to define reason and

unreason by his

utilitarianism. According to this, it

is rational

to seek pleasure and

avoid pain, and irrational to avoid pleasure and seek pain

(unless that

gives you some kind of pleasure). This is probably a

definition of reason

and unreason, but not of madness. According to Bentham, all

human actions

should be explained (scientifically) as an effort to minimise

pain and

maximise pleasure. An example of this is that if you were

hungry and food was in front of you, you would eat the food -

resulting in

pleasure. You would not throw away the food as this would

result in your

still being hungry, therefore pain. However, we can think of

circumstances

when people do not eat the food, even if they are hungry.

These have to be

explained, by utilitarian principles, as cases where some

other pleasure

and/or pain outweighs the pleasure of satisfying hunger.

Foucault (1926-1984), in his books

Madness & Civilisation (Foucault, M. 1961)

and Discipline and Punish - the Birth of the Prison

(Foucault, M. 1975), discussed first the way that

the control of

madness and then the way punishment and prisons have changed

over

centuries. In Discipline and Punishment,

Foucault related this centrally to Bentham's plan

for a

universal institution of control, the Panopticon.

I will examine

Bentham's Panopticon in relation to his

utilitarianism.

A prison or an asylum could be considered as a pain - Because,

however

humane, it deprives its inmates of freedom. Both, also,

subject their

inmates to total control of their lives. [Look at other

aspects. Discuss

deterrence and reform. Consider the importance of anxiety.]

It might be thought, therefore, that people would avoid both

crime and

madness to stay out of prisons and asylums and maximise their

pleasure and

minimise their pain. If this is true, why do people still

behave in ways

that get them sent to prisons and asylums? I will examine the

answer to

this conundrum given by Bentham's twentieth century follower,

Hans Eysenck.

"Bentham Panopticon" or in other words the Inspection-house

was an idea

of a new principle of construction applicable to any sort of

establishment,

in which persons of any description are kept under inspection.

These could

be prisons, mad houses, schools, hospitals and many more.

The plan

The purpose of this construction in the example of madmen was

so that

there would be no risk of them committing violence upon one

another. The

major effect of the panopticon is to induce a state of

conscious and

permanent

visibility that assures the automatic functioning of

power.

In

those times power was thought to be the only way to cure or at

least

control insanity. But did these buildings really cure

insanity? The inmates

were to be caught up in a power situation of which they are

themselves the

bearers. Power should be visible and verifiable. The inmate

will always be

able to see the tall outline of the central tower from which

he is spied

upon. The inmate must never be able to be to see his

surveillance but

always be aware that the possibility of being seen is

constant. This is the

history of the disastrous attempt of the bourgeois to control

insanity. By

cruel and inhumane means. These means did not reduce or

control insanity,

in the contrary it increased and probably got worse.

"Nature has placed

mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.

It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to

determine what we should do"

"the manuscripts from which I have extracted La Théorie

des Peines, were written in

1775. Those which have supplied me with La Théorie des

Récompenses

are a little later" (Dumont

Advertisement)

"General prevention ought to be the chief end of punishment, as it is its

real justification. If we could consider an offence which has been

committed as an isolated fact, the like of which would never recur,

punishment would be useless. It would be only adding one evil to another.

But when we consider that an unpunished crime leaves the path of crime open

not only to the same delinquent, but also to all those who may have the

same motives and opportunities for entering upon it, we perceive that the

punishment inflicted on the individual becomes a source of security to

all." (Bentham, J. and Dumont, P. 1811/1830, chapter 3)

Panopticon

"consisted at

the periphery, an annular building; at the centre, a tower;

this tower is

made with wide windows that open onto the inner side of the

ring. The

peripheric building is divided into cells, they have two

windows, one on

the inside, corresponding to the windows of the tower; the

other, on the

outside, allows the light to cross the cell from one end to

the other. All

that is needed then is place a supervisor in a central tower

and to shut up

in each cell a madman. a

patient, a condemned man, a worker or a schoolboy."

(Foucault, M. 1977 p.-)

"By the effect of backlighting, one can observe from

the tower, standing out precisely against the light, the small

captive

shadows in the cells of the periphery. The panoptic mechanism

arranges

spatial unities that make it possible to see constantly and to

recognise

immediately. It reserves the principle of the dungeon. It

encloses the

imprisoned with full lighting and the eye of a supervisor to

capture every

movement. Visibility is a trap in this composition."

(Foucault, M. 1977 p.-)

| Blackstone - books and articles | Blackstone - weblinks |

| Blake - books and articles | Blake - weblinks |

William Blake was born in 1757 in London his parents were James Blake and Catherine Wright. James Blake was a hosier in London. At a young age Blake had interest in arts; his father had taken interest in this and had encouraged him to attend a drawing school. At the age of ten, in 1767, he was enrolled into Henry Pars drawing school "where he learned to sketch the human figure by copying from plaster casts of ancient statues" (Vultee, D, 2003) [Where did you find the date? 2003? I could not find this]

Blake had a very vivid imagination and had seen images such as angels from the age of four. These visions influenced his poetry.

Once he was fourteen, Blake started engraving as an apprentice with James Basire for seven years. Gothic art and architecture were his main interests.

In 1782, William Blake married Catherine Boucher. William had taught her how to read, write, draw and paint. She worked with him as his assistant and helped him in many of his works. At times there are engravings signed CB rather than WB.

In 1788 William began to experiment printing with copper plates. His Songs of Innocence was produced by this technique in 1789. The plates are poems illuminated by pictures. The outline of the work was made by the copper plate and then the plate was hand coloured, often by Catherine. Because of the way the books were created, no two copies are the same, all the words (printed from the copper plates) do not vary. However, Blake did vary the order in which the poems were bound.

Songs of Innocence and Experience is the combination of two collections of pictorial poetry plates: Songs of Innocence (Blake, W. 1789) and Songs of Experience (Blake, W. 1794e).

The poems in Songs of Innocence

(Blake, W. 1789)

are based on childhood: The themes

portrayed are of youth, play, freedom, naivety and so forth.

The poems are

also written in the manner of a child in that they are very

clear, and

quiet similar to nursery rhymes and hymns.

Piping down the valleys wild,

"Pipe a song about a Lamb!"

"Drop thy pipe, thy happy pipe;

"Piper, sit thee down and write

And I made a rural pen,

Here Blake, the piper, receives his instructions directly from

a child. For

a man who talked to angels, the child is real. But it is also

a magic child

sitting on a cloud and vanishing when its message is

delivered. The symbol

of the lamb from Christian imagery suggests that the child

might even be

the material appearance of God.

The poems are hopeful and optimistic and this may reflect

Blake's political

feelings in 1789, the year of

the French Revolution.

Songs of Experience

(Blake, W. 1794e) was first published in

1794, the year of the terror in France.

The poems of Experience are a contrast to Songs of Innocence.

They seem to

be poems about adulthood, disappointment, misery, criticism of

society and

the negative aspects of adulthood.

Well known Songs of Experience include

The Sick Rose,

London, and

The Tyger. Often there seems to be a balancing poem

in

Experience for one in

Innocence.

A good example that shows these characteristics about misery

and despair is

the poem

London. This poem is based on society

having to suffer

the consequences of the state and society due to passed events

such as the

Industrial Revolution. This had caused secularisation which is

expressed

through

"the blackening of the church walls". And, he says

"Bloods run down

palace walls". Blake was against authority and

institutionalised

religion,

and sexual repression.

Piping songs of pleasant glee,

On a cloud I saw a child,

And he laughing said to me:

So I piped with merry chear.

"Piper, pipe that song again"

So I piped, he wept to hear.

Sing thy songs of happy chear-

So I sung the same again,

While he wept with joy to hear.

In a book, that all may read."

So he vanish'd from my sight,

And I pluck'd a hollow reed,

And I stain'd the water clear,

And I wrote my happy songs

Every child may joy to hear.

| Burke - books and articles | Burke - weblinks |

| Comte - books and articles | Comte - weblinks |

French sociologist Isidore Auguste Comte was born on the 20th January 1798 in Montpellier, France (Comte, A. 1974, pp7). The first of Comte's `Cours De Philosophie Positive' was published in 1830 and the last of the six coming in 1942.

Comte invented the word positivist for his conception of the scientific, as distinct from the theological and philosophical. The positivist seeks to describe the world in terms of observable objects' causes and effect. This philosophy was set out in his six volume Cours de Philosophie Positive between 1830 and 1842. In 1853, Harriet Martineau published a two volume The Philosophie Positive of Auguste Comte (Comte, A. 1853), which was a condensed version of Cours de Philosophie Positive which she had "freely translated" into English. John Stuart Mill's Auguste Comte and Positivism (Mill, J.S. 1865), in 1865, made Comte even better known to English readers. I have also used Stanislav Andreski's The Essential Comte (Andreski, S. 1974), and Introduction to Positive Philosophy by Auguste Comte (Comte, A. 1970), which is a 1970 translation by Frederick Ferre of the first two chapters of the first volume of Cours de Philosophie Positive.

Auguste Comte, argued that the distinction between theology, philosophy and science is crucial to understanding how thought develops and how we obtain true knowledge.

Comte argued that theology, philosophy and positive science relate to each other in the evolution of human thought. Alone, theology or philosophy cannot produce any real knowledge, but each is necessary for the development of science in which we find real knowledge.

Nicola McLaughlin examined the relation of science, philosophy

and theology

in writings

of Thomas

Aquinas, Auguste

Comte and

Bertrand Russell. She pointed out that, in contrast

to Comte's

three stages of knowledge, Aquinas and Russell have only two

elements to

their foundations of truth. Aquinas makes his connection

between theology

and philosophy. Russell relates only philosophy and positive

science.

We can argue that Aquinas' did not discuss positive science because it was ahead of his time. He was writing in the thirteenth century. If we agree with Comte's idea, we could argue that human understanding had not yet developed to this stage. Aquinas had not lived to see many of the great discoveries that Comte knew about. Russell, on the other hand, is a twentieth century writer, and specifically dismisses theology as a source of knowledge. Russell argues that theological (metaphysical) statements are "meaningless".

Although Aquinas was concerned with theological thinking, which is about unobservable things, and Comte was concerned with observable things, both are concerned with cause and effect. Aquinas uses it in his attempt to prove the existence of God, while Comte argues that determining the cause and effects between observable things is the way to find truths and form scientific laws.

Like Comte, Russell believes in the need for positive science. However, the importance that he places on theories and having a critical and questioning nature, means philosophy plays a crucial role. One of his greatest philosophical questions was whether it is possible to know anything at all. This question arises because Russell believes observations are the foundation of knowledge, but says that we cannot trust our senses. If we cannot trust what we know by our senses, Comte's method may be no more reliable than Aquinas', who has faith in something he cannot observe.

| Cooper - books and articles | Cooper - weblinks |

| Darwin - books and articles | Darwin - weblinks |

| Dench - books and articles | Dench - weblinks |

| Dewey - books and articles | Dewey - weblinks |

| Durkheim - books and articles | Durkheim - weblinks |

links for Durkheim on crime and punishment,

For Durkheim and community

Contents

authority and power in family, politics and education -

Durkheim's general theory of society, morality and discipline

Durkheim on politics and power

Durkheim on the stages of childhood and beyond

By Dina Ibrahim

Durkheim: Life and works

Emile Durkheim

(15.4.1858 to

15.11.1917, was a French sociologist.

He was a French Jew born in Épinal in Lorraine, north-east France.

His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were rabbis.

Durkheim obtained his baccalauréat ès lettres at the

Collège

d'Epinal in 1874. In 1875 he obtained his baccalauréat ès

sciences

at the Collège d'Epinal and distinguishes himself in the Concours

général.

Durkheim moved to Paris. In 1877 and 1878 Durkheim failed

his first and

second attempts at the entrance examination at the

École normale suppérieure.

Near

the end of 1879 Durkheim was, at last admitted to the

École

normale

suppérieure began

studying philosophy there, under

the tutelage of Charles Renouvier and Fustel de Coulanges

1881-1882 Jules Ferry laws established free primary school education

for all French children which would be taught by lay teachers rather than

priests. Religion was not taught in these public schools.

1882 Durkheim passed the aggrégation (the

competitive

examination

required for admission to the teaching staff of state secondary schools, or

lycées), and began teaching philosophy.

In the same year, the Faculty of Letters at Bordeaux established France's

first course in pedagogy for prospective school teachers.

Autumn 1882 Durkheim began teaching philosophy at the Lycé de

Sens (Secondary School in Sens, seventy miles south-east of Paris)

1882-1885 Durkheim taught philosophy at various secondary schools

and became a popular figure with students. (Rizwan - no source)

1885, Durkheim's published reviews of works by Schaeffle,

Fouillée, and

Gumplowicz in the Revue philosophique.

From

1885 to 1886 Durkheim was in Germany, where he

studied at Marburg, Berlin, and especially Leipzig. When he returned from

Germany, he published "Les Études de science

sociale" in the Revue philosophique.

In

1887 Durkheim published "La Philosophie dans les

universités allemandes" and "La Science positive de la morale en

Allemagne" on the basis of his visit to Germany. In the same year, he

was appointed

"Chargé d'un Cours de Science Sociale et de

Pédagogie" at

Bordeaux University in

1887.

Robert Alun Jones says that one reason for his

appointment was

that Louis Liard, the Director of Higher Education in France,

Durkheim's opening lecture of his course on "La Solidarité sociale"

at Bordeaux, was later published as "Cours de science sociale: leçon

d'ouverture"

At Bourdeaux from 1887 to 1902 Durkheim spent most of his time lecturing on

the theory of history and practice of education. Each Saturday morning,

however, he also taught a public lecture course on social science, devoted

to specialized studies of particular social phenomena, including social

solidarity, family and kinship, incest, totemism, suicide, crime, religion,

socialism, and law. (Marviana - no source)

1892

Durkheim's

latin thesis on Montesquieu.

1893 De la division du travail social

(

Division of Labour in Society in which he

tried to show that societies are real and that the reality of societies

lies in something that he calls

solidarity. He identified two types of

solidarity present in all societies: solidarity through similarity

(mechanical solidarity) and solidarity through difference (organic

solidarity). The division of labour in society, he argued, created

solidarity through complimentary difference. It develops in the course of

human history to strengthen the solidarity provided by mechanical

solidarity.

He also said punishing crime is a way a society defines the

way it

thinks, reinforcing its mechanical solidarity

If this be so, the remedy for the evil is not to seek to resuscitate

traditions and practices which, no longer responding to present conditions

of society, can only live an artificial, false existence. What we must do

to relieve this anomy is to discover the means for making the organs which

are wasting themselves in discordant movements harmoniously concur by

introducing into their relations more justice by more and more extenuating

the external inequalities which are the source of the

evil"

1895

Les Règles de la méthode

sociologique

(Rules of

Sociological Method) argued that if we want to be

sociologists

we should "treat social facts as things".

He also argued that crime is necessary and normal for

society.. It is a social fact of all societies because by

punishing offences a society defines its moral boundaries:

It is also a necessary social fact because societies need deviance to

evolve.

Durkheim founded the Année

sociologique,

the first social science journal in France, in

1896. At this time, the university at

Bordeaux and the new

Chicago University in the United States, were two main world

centres generating "sociology"

1897

Suicide Durkheim attempted to show that even

such a personal act as suicide was also ultimately determined by social

conditions and not psychological ones.

C'est en 1899, que des intellectuels décident de créer, en

face de la Sorbonne, l'école des hautes études sociales. Dans

l'aventure, des universitaires de renom : le philosophe émile

Boutroux, les sociologues Gabriel Tarde et émile Durkheim, des

historiens tels Charles Seignobos ou Ernest Lavisse, des écrivains :

Georges Sorel, Romain Rolland, etc. (Wikipedia)

In 1899, leading intellectuals decided to create, opposie the Sorbonne,

an institute of advanced social studies. Well known academics involved in

the venture included the philosopher émile Boutroux, sociologists

Gabriel Tarde and émile Durkheim, historians such as Charles

Seignobos or Ernest Lavisse, writers: Georges Sorel, Romain Rolland, etc.

Durkheim was one of the main lecturers at the Congress International de

l'éducation Sociale, in the

Paris World Fair (Exposition

Universelle). Lecture on

Rôle des Universités dans l'éducation sociale du

pays

Durkheim published

"La Sociologie en France au 19e siècle."

1901

Durkheim's last Sociology lectures at

Bordeaux were

on the history of sociology. All that survives of them is

his article on

Rousseau's Social Contract. This argued that Rousseau

bridges the

gap between state of nature theory and sociology

Durkheim published

"Deux Lois de l'évolution pénale"

Durkheim published the second edition of

Les Règles de la méthode

sociologique

Mauss took up a chair in the 'history of religion and uncivilized peoples'

at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in 1901. It was at this time that

he began drawing more and more on ethnography (Wikipedia)

1901 to 1904 A series of laws aimed at controlling the

activities of religious congregations, prohibiting their members from

teaching, and disbanding orders whose sole purpose was to administer and

staff education institutions.

(Sarah. A. Curtis)

7.6.1902 to 25.10.1906 Bloc des gauches (Coalition of the

left) in power in France.

See Wikipedia

En 1902, Durkheim est nommé à la faculté des lettres

de l'université de Paris. Il est également professeur des

écoles normales qui forment les instituteurs de la République

HEI-HEP : c'est lui qui impose la sociologie comme discipline

universitaire. C'est à cette époque qu'il publie Les Formes

élémentaires de la vie religieuse (1912), ainsi que plusieurs

autres articles (Wikipedia)

In

1902,

Durkheim was

appointed Chargé d'un Cours

(Professor in 1906)

at the Sorbonne University

in Paris and took over the Science of Education course vacated by

Ferdinand Édouard Buisson.

Durkheim gave his first lecture - later published as "Pédagogie et

sociologie" - of his course on "L'Education morale."

The last 18 of 20 lectures (1902/1903, repeated 1906/1907) were published

after Durkheim's death as

Moral Education. A

study in the

Theory and Application of the Sociology of Education with

a forward by

Paul Fauconett

Durkheim published the second edition of

De la division du travail social.

In Britain a Sociological Society was founded and sociological teaching was

begun at the University of London by Patrick Geddes, Edward Westermarck,

A.C. Haddon and L.T. Hobhouse

Durkheim prepared a paper for the

launch of the Sociological Society in London

1903 Durkheim and Mauss "Primitive Classification"

1903 Durkheim and Paul Fauconnet

"La sociologie et les

sciences sociales."

7.7.1904 Law forbidding all members of religious orders, whether

authorized or not, to teach.

30.7.1904 Rupture of diplomatic relations with the Vatican

1905

9.12.1905 Law on the separation of Church and State.

See Wikipedia

Durkheim published "Sur l'organisation matrimoniale des

sociétéaustraliennes."

The Catholic philosophy journal Revue néo-scolastique published a

series of articles by the Belgian priest Simon Deploige attacking

Durkheim's elevation of "society" to a power superior to that of the

individual. Durkheim responds in a series of letters to the editors

1906 Durkheim became

Professor of the Science of Education.

In 1913 the

title was changed to Professor of "Science of Education and

Sociology".

11.2.1906 and 22.3.1906 Meetings of the

Société Française de Philosophie at which Durkheim

presented

his papers

"La Détermination du fait moral."

Simon Deploige' Le conflit de la morale et de la sociologie

[With special reference to the works of Emile Durkheim]

Originally published in French by Institut Superieur de Philosophie,

Louvain (1910?).

Translated into English by Charles C. Miltner in 1938 as The conflict

between ethics and sociology [St. Louis, Mo; London: Herder book]

1912

The

Elementary

Forms of Religious

Life,

"both

resented the German pre-eminence in social science and was

intrigued by

Durkheim's suggestions for the reconstruction of a secular,

scientific

French morality."

(Jones, R.A. 1986)

See the chart of Saint Simon

See the chart of John Stuart Mill

At the end of The Division of Labour, Durkheim says:

"morality - and by that must be

understood not only moral doctrines, but customs - is going through a real

crisis.... Profound changes have been produced in the structure

of our societies in a very short time; they have been freed from the

segmental

type with a rapidity and in proportions such as never before been

seen in history. Accordingly, the morality which corresponds to this social

type has regressed, but without another developing quickly enough to fill

the ground that the first left vacant in our consciences. Our faith has

been troubled; tradition has lost its sway...

"Durkheim sets out the boundaries of sociology, its object and

method of study, arguing that an organised collectivity of people is an

entity in itself ("sui generis"). Within it, all individuals play a

collective role in maintaining and developing the society. One way Durkheim

demonstrates this is by explaining how certain institutions such as

religion, law and language exist before the individual is born and carry on

existing after his/her death showing that they are independent and external

realities (see: Durkheim, 1895/1938, p9). The study of society should

therefore be distinct from other sciences such as psychology; the object of

study for sociology is the collectivity, not the individual." (Rizwan -

adapted)

"A social fact is to be recognised by the power of external coercion which

it exercises or is capable of exercising over individuals, and the presence

of this power may be recognised in its turn either by the existence of some

specific sanction or by the resistance offered against every individual

effort that tends to violate it."

"His lecture courses were the only required courses at the

Sorbonne, obligatory for all students seeking degrees in philosophy,

history, literature, and languages; in addition, he was responsible for the

education of successive generations of French school teachers,"

Jones, R.A.

1986 pp 12-23)

"Every

mythology is fundamentally a classification, but one which

borrows its principles from religious beliefs, not from scientific ideas"

(pp 77-78)

|

Joseph Ward Swain (1891-1971) wrote in 1916:

From 1913 to 1915 I was in Europe, studying especially at the University of Paris, but also carrying on private studies at Leipzig and London. During both winters I was regularly enrolled at the "Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Section des Sciences Religieuses," at the University of Paris ; at the end of the first year I was promoted to the grade of "eleve titulaire," and at the end of the second I presented a dissertation entitled "Hebrew and Early Christian Asceticism." Owing to the turmoils of war, the faculty have not yet passed upon this dissertation, but in case it is accepted, I shall receive the grade of "eleve diplome" of the section. The year 1915-16 I spent in graduate study at Columbia. I have translated into English the work of Professor Emile Durkheim, of Paris, entitled " The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life " (London : George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. ; New York: The Macmillan Company, 1915, pp. xi-f-456). |

3.8.1914 German invasion of Belgium and northern France

Durkheim' son André, was sent to the Bulgarian front late in 1915. He was declared missing in January 1916, and in April 1916 was confirmed dead.

15.11.1917 Death.

Durkheim developed Rousseau's' theory that society is not just the sum of its individual members into a theory that society is a reality in itself. He considered that humans are by nature social and that society is not something that came about by individuals uniting together, but something that has always existed. Durkheim's theory is about "social facts" which are social realities external to the individual and which constrain the individual. The concept of social facts between individual and society is the notion that they are bound together by social bonds which are moral in nature. This means that moral authority rather than naked power is the force that will bind society together.

Oby Barnes examined what Durkheim says about authority and power in family, school and society, using his book on Moral Education.

I am making a study of just one of Durkheim's lesser known books Moral Education. A Study in the Theory and Application of the Sociology of Education (Durkheim, E. 1925) My motive for doing so is that I want to understand what he says about authority and power in a context that I can understand: bringing up children. This work of Durkheim's relates to the class room, rather than the family. One thing I do in the essay is to consider how Durkheim's theory of authority and power relates to the family on the one hand and politics on the other.

Durkheim's course on moral education was the first in the science of education that Durkheim offered at the Sorbonne in 1902-1903. He had for some time sketched it out in his teaching at Bordeaux. This course consisted of twenty lectures.

Durkheim's general theory of society, morality and discipline

Durkheim developed Rousseau's' theory that society is not just the sum of

its individual members into a theory that society is a reality in itself.

He considered that humans are by nature social and that society is not

something that came about by individuals uniting together, but something

that has always existed. Durkheim's theory is about "social facts" which

are social realities external to the individual and which constrain the

individual. The concept of social facts between individual and society is

the notion that they are bound together by social bonds which are moral in

nature. This means that moral authority rather than naked power is the

force that will bind society together.

Durkheim believes that science can help us determine the way in which we

ought to behave. He bases morality in reason rather than religion.

To him morality means consistency, regularity. He believe that what is

moral today must be moral tomorrow that is to say that it will never

change. What is morally right in 2001 must be morally right in 2006.

No matter the situation or condition. He argues that morality and

regularity of conduct and authority are aspects of one thing he calls

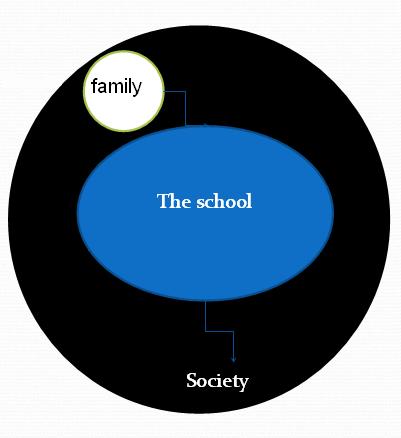

discipline. Therefore the school environment plays an important role in

moral education that faces a child when he comes to school. The school is a

more extensive association than the family or the little groups of friends

but are brought together on the basis of similar age and social conditions.

In that respect Durkheim said that it resembles a political society. In the

sense that

Durkheim compares to animals

Durkheim believes that discipline should not be viewed as sheer constraint.

He gives two reasons for this:

* Firstly it shows us the appropriate modes of response without which order

and organised life will not be possible.

* Secondly, it helps to respond to the individual's need for restraint

To Durkheim, any behaviour dominated by self interest is not regarded as

moral. He believes that morality is attachment to, or identification with,

a group. A group is an aspect of one thing, which is society. Discipline is

seen in the society as the father commanding us to do our duty.

Durkheim's view of authority

According to Durkheim authority is a

That is to say that it not important whether the powers are

real or not. Durkheim says that what matters is that they real in peoples'

minds. For example a magician is an authority to those who believe in him.

Durkheim calls this the "definition" of authority: That is, the people

believing in their

mind that some thing or person has, in relation to them, superior powers.

This is authority, and Durkheim argues that it can only be given by

society.

Given the definition, he says

In an earlier work Durkheim makes it clear that this believing in by the

people flows from respect, rather than fear:

society is responsible for all the wealth of civilization, it is

the society that accumulates and preserves the treasures that are

transmitting from age to age, it is through society that the riches get

to us.

Therefore we are obligated to society since it is from it that we

receive these things. These are our believe in our mind whether this is

true or not or rather imaginary but we allow it to have authority over

us. Durkheim believe that society is a moral authority and he is pleased

to believe that there are at least some individuals who owe their

eminence only to themselves and their natural superiority. Not only do we

not respect the sheer physical strength but we scarcely fear it. However

before authority can be establish, the public or society will first see

something of moral value to it. Hence it will register in our mind

otherwise it will not be taken seriously at all. In other to for it to be

effective, our social organisation is inclined to prevent the abuse of

power and consequently to make it less formidable.

Durkheim on politics and power

A

despotic ruler is one who rules according to his or her

unregulated will. According to Durkheim a

despot is like a child he has a child weakness

because he is not master of himself. Durkheim argues that

For this reason he said that some political parties that are too strong and

do not take account of strong minorities cannot last. It will not be long

to their downfall because of their excessive power that they establish

because there is nothing to restrain them, they result to violent extreme

which are self destroying.

When a party is too strong, it escapes itself and is no longer able to

control itself because it is too powerful. He says it is not possible for

us to control ourselves through our

own efforts, without some external pressure. So the capacity for

self-control is itself one of the chief powers that education should

develop.

Durkheim believe that in order to set limits ourselves, we must feel the

reality of these limits.

Durkheim believe that there is one association that among all the others

enjoys a genuine pre-eminence and that represents the end, par excellence,

of moral conduct. That is that is the political society, that is the nation

conceived of as a partial embodiment of the idea of humanity. (Durkheim

E.1925.p 80).

Political society does not represent family members where the sentiment of

solidarity is derived from blood relationship nor does it represent little

groups of friends and companions that have taken shape outside the family

through free selection. According to Durkheim

Therefore there is a great distance between the moral state in which the

child finds himself as he leaves the family and the one toward which he

must strive.

Durkheim on education

According to Durkheim education is especially urgent today in our life. To

him

For twenty years, France had been providing a religion-free education in

its publicly funded schools. This meant, children were sent to school for a

moral education which was not "derived from revealed religion". Instead, it

rested "exclusively on ideas, sentiments, and practices accountable to

reason only".

This change had disturbed traditional ideas and old habits, and posed new

problems.

The school is there to establish discipline - And, according to Durkheim,

discipline is not just a constraint

"necessary when it seems indispensable for

preventing culpable conduct" (Durkheim E. 1925a p 43). It is not

something to be used just to stop the school descending into chaos. It is

much more important than that.

Discipline, in itself, is a factor of education. It builds moral character.

There are essential parts of moral character which can only be built

through discipline. We need discipline to be able to teach our children to

control and limit their desires. It is by limiting his, or her, desires

that a child learns to define what he or she is seeking. Durkheim says that

limiting our desires, and defining what your goals are, is the way that we

achieve happiness and moral health.

Morality is basically a discipline and Durkheim says that all discipline

has a double objective. On the one hand, discipline

promotes a preference for the customary. On the other hand, it imposes

restrictions that regularise and constrain.

As the school is the first place a child to learn how to deal with life in

future, then discipline in the classroom is very essential because if the

teacher does not correct on that child misbehaving the other may think that

it is ok for them to do the same, which can lead to disruption in the

classroom.

Therefore the idea is to transform the confused. The whole idea of

discipline is to see morality clearly as it is. To show everyone what is

moral, even in the midst of the kind of diverse and confused ideas that

surround moral issues in practice. This cannot be done by simply

substituting our own conceptions of what is right for the ideas of the

child. Everything we do in the school should be aimed at the children

learning together what morality really is. This is where the teacher's

authority is and why he or she should exercise power.

The school prepares children for society, and so morality is where

education must begin and where it must always end.

Kerri Bowles