| Functions - Forms - Landscapes |

|

Notes on asylum architecture

Using the work of several people researching the history of function and form in the buildings and grounds used for psychiatric purposes. The index to the right will be developed as a means of finding ones way around.Extracts from Jacobi, C.W.M. 1841 On the construction and management of Hospitals for the Insane

" What is the most desirable situation for an hospital for the insane?We may presume, without further question, that the same circumstances, in regard to situation, which are found by a person who is free from any morbid tendency, to have a beneficial influence on his mental feelings, will generally, in some degree, contribute to the restoration of a mind diseased.

The establishment should be situated, then, under a mild sky, in an agreeable, fertile, and sufficiently dry part of the country, where the surrounding scenery, diversified with mountains, valleys, and plains, is calculated to enliven the spirits of the beholder, and invite him to wander and explore its beauties.

In the next place, there should be an unfailing spring of good drinking water, a running stream which will afford a constant supply for other purposes, and easy communication with some large market town, bestowing opportunities for procuring the necessaries of life, and for social and scientific intercourse.

So much of general attributes. As we descend into particulars, however, it admits of some doubt, whether, if the situation be left entirely to choice, it would be more advisable to erect the buildings of the establishment on a plain, or on an eminence; and whether they should be quite solitary, or contiguous to some town or village. And this certainly deserves some consideration.

A situation upon a moderate, easily accessible eminence, of from 150 to 250 feet at the highest, above the level of the nearest river, and commanding an extensive range of agreeable scenery, and an unconfined view of the heavens, is certainly productive in a mild and serene climate, of exhilarating and joyful emotions. Besides the advantage of a dry and salubrious atmosphere conferred by such a situation, it is not its least recommendation, that it enables the patients to extend their view far and wide, over the boundary walls or hedges of the estate, as these may be placed at the lowest purl, of the establishment. The patients are thus not so easily reminded every moment of their incarceration, and, through it, of their other miseries.

Whilst an establishment in a level situation is deprived of all these advantages, and must, therefore, generally cause a less kindly impression, both on diseased and healthy minds; still it enjoys other very important advantages, not possessed by the former.

The principal of these is the abundant supply of water, which a full stream affords for the baths, washing, and every kind of cleaning, as well as for the most appropriate construction of the privies.

Other advantages of a level situation, consist in the greater facility of enlarging the ground-floor of the buildings, to any required extent; in the greater protection from the influence of the winds and storms, thus materially affecting the consumption of fuel, and the ease of warming the day-rooms in winter; in the easier conveyance and delivery of all articles of consumption; and lastly in this, that the patients are more sheltered from the prying gaze of the inquisitive, to which they are too much exposed on a hill, which lies open to these glances from all sides.

All these advantages are met by exactly correspondent disadvantages which, in the situation of an establishment upon a hill can never be entirely overcome, and only even partially diminished, by a great outlay of money.

{fotnote: I cannot doubt that a piece of ground on a level with a running stream, would be, in general, a highly inexpedient site for a lunatic asylum in England. The dampness of such a situation in our humid climate - especially in the time of heavy rains, when the stream may lie swollen into a flood, is an irremediable evil which has no counterpart in an elevated situation, unless we speak of such an extreme height, as no one would contemplate for such a purpose. Besidcs there is scarcely any thing more important, in regard to the site of an asylum, than that it should afford a most complete drainage; and this can hardly be obtained, except in a somewhat elevated situation: and this character is by no mean' incompatilible with the advantage of retirement and shelter. (Editor)}

In the same way, the advantages and disadvantages at tending the entirely isolated situation of an establishment, and one contiguous to a town or large village, appear very nearly equivalent to each other. The neighbourhood of a market town certainly affords many conveniences and comforts, both in an economical point of view, from the promptitude with which various wants may be supplied, by the resident mechanics and tradespeople, and in other respects from the intercourse which may be kept up with the inhabitants. On the other hand, the vicinity of a town containing a population not entirely agricultural, but which consists-of mixed classes, is so annoying and inconvenient, from the intrusive curiosity excited by the patients, and the incessant scrutiny to which they are exposed at every step they take abroad; the difficulty of completely releasing them from the usual noise and tumult of society, however desirable it may be that many of them should enjoy this liberation, is so much increased, and so much facility afforded to the servants, and in some degree to the patients also, for carrying on forbidden intercourse with the inhabitants, that these reasons would compel me to select a situation nearly solitary. I should prefer, however, most of all, one in which the establishment should lie about half an hour's walk from a town. All the advantages to be thence derived, would then be within reach, divested of the prejudicial accompaniments of immediate contiguity.

Forms of asylumJacobi discusses the following "forms at present chiefly recommended for the buildings:Several distinct quadrangles having a certain connection and relation with each other. Examples: "the one at Ivry, the house for females at Charenton, and the large establishment at Rouen"..."All these were builit according to the maxims of the excellent Esquirol The one Jacobi describes was at Rouen: "The institution is adapted for three hundred patients, and intended to receive the incurable, as well as the curable. In front of the more ancient buildings, which had been used a long time previously as a lunatic asylum, five handsome quadrangles have been erected, one story high, containing the dwellings of the patients..." H form Example: Wakefield. The junction building has the "house- keeping" and common rooms for the use of both sexes and the two long wings are used one by the women and the other by the men. Lineal Form "in which all the buildings are ranged in a straight line... the domestic apartments are most properly placed in the centre... the divisions for the male and female patients...on their respective sides, in such a manner , that the convalescents and least deranged patients occupy the most distant wings." Examples: Bethlem (1815) and Perth Star or radiating Example: Glasgow Pavilions - [Pavilion is later used for a large, Florence Nightingale style building - We might call this early colony plan] "...it has been strongly recommended, that a certain number of distinct pavilions one story high, should be erected in a large piece of ground laid out like a park, and appropriated to the different classes of insane patients.... such an idea could only be realised in the case of a small private establishment, for twenty-five or thirty patients at the outside, and ... it would require a much milder climate than we are favoured with in Germany... An institution for two hundred patients, arranged on such a plan, would be so lost and dispersed on its own ground, that any regular superintendence and medical treatment of the patients would be impossible, even in the finest weather..." No Jacobi example. Compare Brislington House (1806) and the Colony Plan 1902 -1967 |

| Jacobi's model falls in the period where there are few examples in Susan Piddock's sample. Few of the asylums after 1845 met Jacobi's requirement of having 200 patients. One of these was Buckinghamshire Asylum . Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire came close at 252 and 250 patients respectively. All favoured a linear layout, but none of the asylums followed Jacobi's suggestion of arranging houses around courtyards. Most met the requirements of a country location with the exception of Essex Asylum which was placed in the urban setting of Brentwood. While there was a strict separation of the sexes, the linear design meant that the various classes were visible to each other to some degree. Certainly all the asylums offered classification of the patients and small spur wards which could be used to separate the noisy and infirmary patients if necessary. As these asylums were for paupers there was no emphasis in providing different rooms for the various social classes as Jacobi recommended. |

|

Wakefield

Model of the original 1818 building made by Mr A.L. Ashworth, Hospital

Secretary 1961-1973, using the original plans and drawings fo the asylum

"The really old part of the hospital is shaped like an H where the cross piece has been extended on both sides so that it resembles two plus signs joined together. While the outside of the building preserves and eighteenth century dignity and balance, its plan is strictly functional, conforming to nineteenth century scientific theories of social control. This is in fact the 'double panopticon' which is to be found in so many prisons and places of correction - and mental hospitals - built at this period and for many years afterwards. Once having taken up position at one of the points of intersection, whoever is in charge can look anywhere, keeping an eye on things north, south east and west along the length of the four radiating corridors. Modern psychiatric nurses have never liked this arrangement. Apart from not being all that effective for 'ambulant' patients, it brings home the custodial role in a way that is nowadays felt to be unacceptable. This, however, is the architecture that they have inherited and must make the best of. |

|

Early - later adapted to corridor - Most early county asylums do not seem to have followed a typical plan. In most cases, however, a Corridor type layout was later adapted around them. I am assuming a date of 1810-1830 for these. Examples could be Nottinghamshire County Asylum (1810), Norfolk County Asylum (1814), Staffordshire County Asylum (1818), West Riding of Yorkshire County Asylum (Wakefield) (1818), [described as H form at the time],

RADIAL PLAN

Long wings radiating from a central (often semi circular) hub. Considered

inhumane even in its own time and only really implemented in the south-west

(other than prisons). The close nature of the wings at the point nearest

the hub would allow little access for air and light to the buildings and

airing courts between them. One source suggests this plan offered a

deterrent to potential admissions as asylum care would have been preferable

(and more expensive) to the workhouse. Eg. The main block at St. Lawrences

(Cornwall, 1820), and Exe Vale/Exminster

(Devon, 1845).

A radial plan with only two wings - radiating on the same diameter line,

either side of the hub - is a

corridor plan

CORRIDOR PLAN

Originally Corridor - A long running and variable group

1830-1890. They are

typified

by a (often projecting or recessed) central block including admin and

former officers quarters, flanked by long wings either side, each with

appropriate working areas and segregated by sex. Built to two or three

storeys in height. Typically (as the name suggests) a corridor or 'passage

of communication would run the length of the building to ease access.

Widespread across England and Wales.

Eglinton, Ireland

PAVILION PLAN

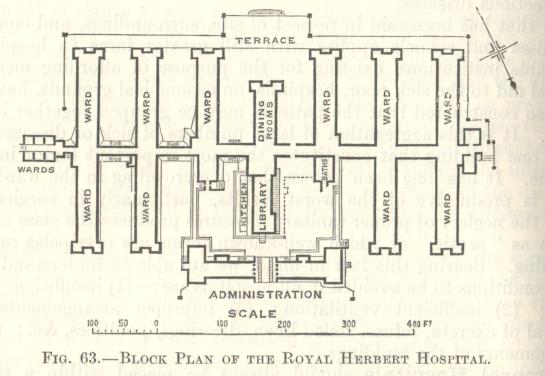

The first Pavilion type hospital was the Royal Herbert, on Shooters Hill

Eltham, a military hospital.

[Opened 1.11.1865. See

external link].

The second was St. Thomas' in London [opened 1871]. These were designed on principles recommended by Florence Nightingale. The Architect of Royal Herbert being her nephew. Therefore all pavilion and corridor-pavilion types should post-date these

Corridor-Pavilion: About 1870 to 1890. An ill-defined group of

buildings intermediate in character between the two types. Thanks to its

vague definition, I cannot really seem to identify many to this layout.

Possibly used at St. John's and St. Lukes (on a radial corridor) divisions

at Whittingham (Lancs), De La Pole (Hull). The first and last show a

courtyard type plan with wards facing into this area.

Pavilion - 1870 - 1907 (in asylums). A hugely widespread type, and

essentially the first common hospital plan and greatly advocated by

Florence Nightingale, but little used within asylum design.

The principles

of it seem to have been utilised in the echelon plan.

i, Standard Pavilion - Usually consisting of a long linear corridor with

individual ward blocks to allow free passage of air and light. Central

admin block. Hall and services could be central or remote. Eg. Hellesdon

(Norwich), Darenth Park (MAB)(original block and first annexe)

ii, Dual - Axial services and facilities flanked on either side by long

corridors with individual blocks. The sheer size of these complexes blocks

made them operationally difficult and they were initially intended as

somewhere to segregate incurables and chronic cases away from other

patients. Typified by the huge Caterham and Leavesden Imbecile Asylums of

1870 for the Metropolitain Asylums Board of London (which used the pavilion

plan in nearly all of its hospital buildings). Banstead 1877 (for

Middlesex) and Possibly Winwick (1897) may have been the only non-imbecile

examples. Calderstones Certified Institution 1905 (Lancs Asylum Board) is a

late example.

iii, Radial Pavilion - An oddity, and intermediate between the standard

pavilion and the development towards the echeon plan. Individual ward

blocks arranged around a semi circular corridor with axial office and

service accomodation.

Cane Hill (Surrey 1883) is the only true example but

could include

Whittingham's St. Luke's Block (which had remote services) in

some respects.

iv, Irregular - eg. The Manor Certified Institution (at Epsom for London

CC) was a large structure consisting of temporary pavilions arranged around

an L- shaped corridor, with a pre-existing mansion as its hub and offices.

Darenth Park 2nd Annexe consisted of two groups of five y-shaped pavilions

linked by corridors.

ECHELON PLAN

Echelon - 1880 - 1932. Largely superseded the

Pavilion plan of Asylums

in all but the Metropolitan and Lancashire Asylums Boards. Its sudden rise

in popularity being the arrangement of wards, offices and services within

easy reach of each other by a network of interconnecting corridors.

Typically forming a triangular, trapezium or semi-circular format.

i, Broad Arrow 1880-1890. The earlier form of echelon plan

consisting of the

typical layout with services and wards (segregated by sex) located on a

wide spreading complex. Broad Arrow wards were essentially detached

pavilion blocks linked by stubby corridors to the main corridor network.

Coney Hill (Gloucester 2nd) by Giles and Gough would have been the first

had it been completed to plan.

High Royds (Menston, West Riding) 1888 by J.

Vickers-Edwards was probably the best example.

ii, Compact Arrow

1890

- 1932.

This plan revolutionised the construction of

Asylums and Mental Hospitals and was probably the most practical type

devised. The linking corridors of the Broad Arrow were retained, but

instead the ward blocks 'hugged' the main corridors rather than being

placed away from them. Ward blocks could be either interconnecting or

distinct from each other. Typically these wards would give the appearance

of a zig zag as they were stepped along the main corridor. As in previous

designs, male and female workplaces would be located on their respective

sides with shared services and offices occupying the centre.

Later examples

had detached villas in the grounds for working, epileptic or chronic

patients, and also Acute blocks to avoid incorporation of recent cases to

the main building. Later developments towards

the Colony layout

included

some asylums with open sided corridors and ward blocks becoming further

detached.

Claybury

(opened 1893 in Essex for London County) was the first compact arrow

plan and was greatly praised in its time, becoming the model for asylum

design and its architect

GT Hine

becoming the most accomplished and

successful of asylum architects.

Bexley

(in Kent for London County),

Hellingly

(West Sussex),

Barnsley Hall

(Worcestershire) and most other Hine Asylums are based upon

Claybury. Other architects such as Giles, Gough and Trollope

(

Cheddleton County Asylum, Staffordshire)

and

Tone Vale

(Somerset), Vickers-Edwards

(Storthes Hall - West

Riding)

and many others adopted this principal for their works.

Park Prewett

(by Hine) is of the

later type with open corridors and separate

wards blocks.

Cefn Coed 1932 (Swansea Borough) seems to have been the last

example to be completed.

|

Landscapes:

Sarah's Rutherford's study (9.2003), The Landscapes of Public

Lunatic Asylums in England, includes

nine case studies of asylum history, architecture and landscape:

-

Moorfields Bethlem (1676)

-

The Retreat

-

Brislington House

-

Nottingham

-

Norwich

-

Wakefield

-

Hanwell

-

Derby

-

Middlesbrough

-

Ewell Epileptic Colony

The main thesis analyses the English public

asylum landscape during its development from

1808 to

1845, and subsequent consolidation and variation into

other related types during the main period of public asylum building (from

1845 to 1914).

It analyses the asylum as a distinct landscape type, its principal

influences and context, also the main design influences, particularly the

landscape of the country house estate. It also examines issues connected

with the conservation of this type of landscape, in the face of current

grave threats to the fabric. The work looks at the use of the asylum

landscape, concluding that its principal function was therapeutic. For this

it needed an extensive, ornamented landscape so that patients could

undertake recreational and work activities. A number of individuals were

found to have contributed to the design of various asylums, including

professional landscape designers commissioned to design asylum sites. These

included a previously unknown designer, Robert Lloyd of the

Brookwood asylum, Surrey, who was particularly prolific in this

field, and was associated with at least seven asylum sites.

in the early 17th century, the space in front (and behind?) the main

building contained a single airing court. A second court was added in an

expansion of 1643-1644.

By

the later 17th century Ogilby and Morgan's

map of London shows that there was virtually nothing of the formerly

spacious precinct left that had not

been built upon, apart from the limited space in front of and behind the

main buildings.

But by then it was set in a noisy, crowded location which did

not suit the aspirations of the City

of London or medical requirements for fresh air to combat infectious

miasmata.

Moorfields Bethlem - The landscape - 1676-1815

Until

the mid-eighteenth century, the

Moorfields Bedlam, designed by

Robert Hooke, was the

only significant example of a

purpose-built lunatic hospital in Britain. Major features of Hooke's

Bethlem, in terms of the setting,

accommodation and treatment, provided the model used for other charitable

lunatic hospitals founded in

the eighteenth century and even the publicly funded county asylums in the

nineteenth century. As such its

estate was very influential in asylum construction, including the principal

elements of the estate: the

building, airing courts and forecourt.

The new site selected,

close by Bishopsgate, at the head of Moorfields, was

chosen for its "health and aire",

the benefit of an ample, unsullied fresh air supply and its effective

circulation being regarded by the

Governors as the key to healthy surroundings.

The poem Bethlehem's Beauty (1676) emphasised the

perceived virtues of the new site's healing air:

Th' Approaching Air, in every gentle Breeze,

The Governors employed the prominent architect Robert Hooke (1635-1703),

who was actively involved in

the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire, to design the building.

Largely constructed by 1676, it was

probably only the third purpose-built asylum, after one in

Valencia (1409, destroyed 1512) and the

Dolhuys in Amsterdam (1562).

Andrews states, in connection with the intentions of the Governors, that

they were

The Moorfields Bethlem was in Lower Moorfields, to the west of Bishopsgate.

. Like Bishpsgate, it was outside the north boundary of

the City, although only just so. The site for the building ran parallel

to the ancient London Wall, and only

nine feet (3m) to the north of it, occupying open ground on the site of the

old City ditch which had been

filled in. The site formed the south boundary of, and overlooked,

Moorfields, a series of substantial formal

public open spaces laid out from 1605, which, although largely surrounded

by development, formed a

finger of open space which led directly out to the open fields to the

north.

Moorfields Bethlem was palatial in

scale, even in terms of new constructions put up as part of the building

campaign after the Great Fire,

being intended to accommodate 120 patients. The about 540 feet (166m) long

entrance facade on the north

front was depicted by Robert White in an engraving of 1677

(external link to picture), shortly after

construction, together with parts

of the grounds.

The single-pile building was of two storeys over a

basement, and showed Dutch and French influences in its elaborate external

decoration. The patients were

segregated indoors, at first with males on the ground floor and females on

the first floor. The cells, for

individual patients, led off galleries which served for communication and

for exercise in inclement weather.

John Evelyn was one of the many admirers of new Bethlem, describing it as

"magnificently built, & most

sweetely placed in Morefields". There must surely have been a service

entrance on the south side of the

building, between it and the City Wall, although the space between the two

was only nine feet (3m).

White's engraving clearly shows the grounds and part of the

provision made

for patient exercise.

The outline in plan form of the building and its open spaces in

relation to their setting is also shown

on contemporary maps of London such as Morgan's map of 1682

(external link to map)

The grounds were divided into a

large rectangular forecourt in

front of the building, flanked by two smaller exercise yards. The whole was

approached via the formally

laid out and enclosed lawns of Moorfields, a fashionable recreational space

for the local inhabitants which

had been one of the first such formally designated public open spaces.

Security at Bethlem was of great

concern, as patients were perceived to be continually likely to abscond as

the opportunity arose. As reliable

staff to supervise patients were difficult to find, the Governors had to

rely on making the environment itself

provide the means for ensuring confinement. The first three reports on the

construction of the building by

the hospital's Committee of Governors were largely taken up with matters

concerning the boundary wall

that was to surround the hospital and its grounds, and to confine the

patients.

The existing London Wall was used to form part of the secure 680 feet

(c.207m) long south boundary

wall. On the other sides a wall was to be constructed at 14 feet (4.2m)

high along the sections which

bounded the airing courts, with a coping expressly intended to stop the

lunatics escaping. The exception

was the front, north, wall of the forecourt which ran parallel to the whole

length of the building and divided

it from the adjacent Moorfields. This c.420 feet (c.128m) long central

section of the whole north wall

would be only eight feet (2.5m) high, so

The lowering of the forecourt wall did

not affect security, for the

patients were forbidden to exercise in the forecourt.

(Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives, Bridewell and Bethlem Court of Governors

Minutes, 23.10.1674)

The wall was broken

by six evenly spaced panels of

iron railings, each forming a ten-foot (c.3m) wide clairvoie intended to

enhance the views of the building

from the adjacent and impressively laid out Moorfields open recreational

space. The views were clearly

intended to impress the users of Moorfields, both nearby residents and

visitors alike, and the visitors to

Bethlem itself upon their approach.

The north side of the building and the forecourt are shown in detail on

White's engraving

, with a passer-by

admiring the ensemble. The clairvoie panels were flanked by piers

surmounted by stone pineapples.

At the

centre of the forecourt wall an elaborate triple gateway gave access from

the formally fenced and tree-lined

lawns of Moorfields to the north, between which the visitor approached. The

portentous gateway was

elevated above a flight of steps and surmounted by the

life-sized statues

of two figures depicting raving and melancholy madness,

attributed to Caius Cibber.

From here the visitor crossed the expensively paved

and gravelled forecourt to gain access to the main entrance at the centre

of the building. There were

numerous large windows in the north walls of the ward wings, flanking the

central administrative block,

allowing for the ample ingress of light and air. Those in the raised ground

floor and first floor, in

particular, gave the patients an elevated view of the forecourt, and beyond

this of the designed open spaces

of Moorfields.

The sites of the Bishopsgate Bethlem and the Moorfields Bethlem are shown

on the sketch map

Until

the 1530s the

Bishopsgate Bethlem had

been quite open around the main

building, having gradually acquired a series of gardens and courts.

Following

the Reformation its open site

was gradually reduced in size, with the sale of plots within it.

[See 1559 map]

Robert Hooke's architecture (Moorfield's

Bedlam)

Robert Hooke was a close colleague of Christopher Wren and

designed several

other

institutional buildings in London

including the Bridewell Hospital (1671-78), also for the City of London;

the Haberdashers Aske's Hospital, an

almshouse at Hoxton (c.1690-93); with John Oliver, Christ's Hospital

Writing School (1675-6); as well as several

town and country houses. Hooke's Hoxton building was of similar design to

Bethlem: a long, single-pile building

with an elaborate central block connected by flanking wings to two

pavilions. A large, grassed forecourt appears to

have been used by the inmates for recreation and exercise, and was divided

from the road beyond by a wall and

central gateway, the whole layout in similar formal style to that at

Bethlem. It is illustrated in Strype's edition of

John Stowe's Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (1720). Hooke

only used the single-pile design for

these two hospitals, not for his houses.

Is Fan'd and Winnow'd through the neighbouring Trees,

And comes so Pure, the Spirits to Refine,

As if th' wise Governours had a Designe

That should alone, without Physick Restore

Those whom Gross Vapours discompos'd before

"much more concerned with the 'Grace and Ornament of the _

Building' than with the patients'

exercise or any other therapeutic purpose - New Bethlem was constructed

pre-eminently as fund-raising

rhetoric, to attract the patronage and admiration of the elite, rather than

for its present and future inmates,

whose interests took a poor second place'"

Robert White's 1677 engraving

and Morgan's 1682 map are

the two main illustrative

sources available for Hooke's Bethlem as it was when first built.

The above reports provide a

narrative of the layout of part of the grounds and, together with

White's engraving, provide the basis

for the following analysis of their construction. The committee reports of

13th, 16th and 20th October 1674 were read into the Bridewell and Bethlem

Court of Governors Minutes for 23.10.1674 (Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives)

"that the Grace and Ornament of

the said intended Building may

better appeare towards Morefeilds"

Clairvoie (clear view): a gate, fence or grille placed in an otherwise

solid barrier to provide a clear view of outside scenery or, in this case,

the building inside.

| Bethlem exercise courts | after the 1730s |

The boundary wall also enclosed the two exercise yards, which flanked the forecourt at the corners of the building. The forecourt was several times larger than either of the exercise yards, which were limited in their extent by, apart from the forecourt which divided them, the proximity of Moorfields to the north, the London Wall to the south, and development to the west and east. Two yards were provided "reserved for the use and benefitt" of the inmates, one each for the separate sexes to exercise in. Those patients "well enough" were "permitted to walke the Yards there in the day tyme", so that they could "take the aire in order to [aid] their recovery". (Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives, Bridewell and Bethlem Court of Governors Minutes, 23.101674 and 5.5.1676, and Bethlem Committee report, 16.10.1674.

Each yard was surrounded by the 14 feet (4.2m) high wall, topped with a "Coping _ intended to p'vent the Escape of Lunatickes". Both were laid out with grass and gravel plots of 120 feet (36.5m), with, set into the rear wall, a small pavilion with windows at first-floor level. (Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives, Bridewell and Bethlem Court of Governors Minutes, 23.10.1674 and White's engraving 1677

The upper level of the pavilions may have provided shelter for attendants supervising patients whilst allowing them an elevated view of their charges in the yard, with the lower level providing shelter for the patients.

| Bethlem airing courts after the 1730s | before the 1730s |

By 1786, Bethlem was noted for its "fine gardens" where the patients "enjoy fresh air and recreate themselves amongst trees, flowers and plants".

Marie Sophie von La Roche, 1786 Tagebuch einer Reise durch Holland und

England, being her diary. Sophie in London, 1786 A translation

of the part about England was published, with an introductory essay by

Clare Williams (the translator) by Jonathan Cape in 1933.

Although there was no formal classification by symptoms, there was obviously a category of patients who were allowed to exercise outdoors. Those whose behaviour was deemed to be too wayward or who were physically too unwell remained indoors.

By 1740 the wings had been extended to west and east in L-shaped form, covering much of the site of the early airing courts. Provision for patient exercise was made by reducing the width of the forecourt, such that it only extended half way along each of the original wings. It had also lost the clairvoies formerly sited in the north boundary wall. The open ground formerly flanking the forecourt was given over to airing courts, surrounded by higher walls. The old gateway had been re-sited to the south, much closer to the front door and a curved carriage sweep open to Moorfields now provided more direct access to theentrance to the building, while dividing the forecourt into two compartments. This removed the need for visitors to cross the forecourt on foot to gain admittance. The opening up of the approach physically linked the main entrance to the building with the main axial walk of Lower Moorfields pleasure grounds.

The Moorfields site was abandoned in 1815, when a new site was opened in St

George's Fields,

Southwark. The old building had for long been unsound, having been

constructed very quickly of poor

materials over the unstable infilled ground of the City ditch below the

City wall. The building was

demolished and Finsbury Circus was developed on its site.

Elements drawn from

Bethlem were used at the core of both The Retreat and

Brislington House: These being principally

the airing courts.

The use of moral treatment was manifested in the construction

of further, new elements in the wider landscape.

Samuel Tuke described the grounds and the building, which had been designed

by a London architect and

builder, the Quaker John Bevans. Bevans had designed a number of other

buildings for the Society of

Friends including several meeting houses. The brick building, which by 1813

held 50 or so patients, was

said by Tuke to be designed chiefly for economy and convenience. However,

the layout of the building was also intended to facilitate the

classification of patients in various ways: by gender, social class and by

clinical state. The so-called quiet

patients, those exhibiting non-disruptive symptoms and those being

convalescent, were separated from the

disturbing and disruptive behaviour of more refractory patients. The

division by gender and by clinical

state was manifested in the layout of the building and in the associated

airing courts. Two ward wings, for

the more tractable category of male and female patients, extended in

opposite directions from the central

block and benefited from airing courts adjacent on the south side, and the

associated views out over the

walls to the surrounding countryside. The two courts were divided by a

central path giving access to baths

at the back of them. A semicircular wall, which marked the outer boundary

of the two inner courts for the

more tractable patients, was about eight feet (2.4m) high "but, as the

ground declines from the house, their

apparent height is not so great; and the view from them of the country is

consequently not so much

obstructed, as it would be if the ground was level"

The two main wings led in turn to two smaller wings, almost entirely

detached from the main building,

with associated walled airing courts. Here were housed the more refractory

class, who could be noisy,

unclean in their personal habits, and violent. Because of such antisocial

behaviour, physical isolation was

practised in order to reduce their negative effect on the other patients

and localise the amount of extra work

which they created for the staff. Each of the four airing courts covered

between four and five hundred

square yards (334 to 418m sq.).

For those patients too physically ill or difficult to control to be allowed

beyond the confines of the courts,

the courts were supplied with domestic animals as pets including rabbits,

sea-gulls, hawks and poultry.

Samuel Tuke censured the courts as being too small and confined, this, he

believed, being deleterious to the

patient's state of mind when the boundary of confinement was always so

obvious. However, the sense of

confinement, he said, was alleviated by taking such patients as were deemed

suitable into the garden, and

by frequent excursions into the city or the surrounding country, and into

the fields of the Institution, one of

these being surrounded by a walk, interspersed with trees and shrubs [in

the manner of a ferme orn‚e]. The

criteria for being regarded as "suitable" for these activities related to

physical robustness and whether or not

the patient's behaviour was considered to be too antisocial or whether they

could conduct themselves with a

reasonable measure of self-control.

The French doctor Charles-Gaspard de la Rive published a useful early

account of The Retreat in the

BibliothŠque Britannique following his visit in 1798. It suggests that he

had an agreeable surprise at the

pleasant conditions of the asylum, although Foucault believed that the main

purpose of the institution was

to serve as a repressive instrument of segregation. According to de la Rive

it lay, "in the midst of a fertile

and smiling countryside; it is not at all the idea of a prison that it

suggests, but rather that of a large farm;

it is surrounded by a great, walled garden. No bars, no grilles on the

windows".109 It had 11 acres (4.5 ha.)

of land and was largely given over to growing potatoes, and grazing cows

which provided milk and butter

for the establishment. A one-acre (0.4 ha.) kitchen garden lay to the north

of the building and provided

abundant fruit and vegetables which fed the establishment.

The Retreat also provided a place for recreation and employment for many of

the patients, "being divided

by gravel-walks, interspersed with shrubs and flowers, and sheltered from

the intrusive eye of the

passenger, by a narrow plantation and shrubbery".110 The clothing of the

grounds was apparently a major

feature; fourteen pounds and ten shillings-worth of native and exotic woody

plants were bought in 1794

from the notable York nurseries of John and George Telford, and Thomas

Rigg, at a time when the

erection of the building was hardly advanced.111 For this amount 768 plants

were purchased.

The asylum building was therefore surrounded by the equivalent of a small

country estate, with ornamental

pleasure grounds, and productive kitchen garden and farmland. It fused the

elements which were purely

asylum-related with the type of carefully constructed country house-type

landscape that was being

promoted by landscape improvers and designers such as Humphry Repton (1752-

1818)

Brislington House was the first purpose-built private asylum (1804-1806)

Its proprietor,

Dr Edward Long Fox (1762-1835), was a Quaker, and the

structure and regime were almost certainly influenced by

The Retreat. Brislington House

reflected the layout of the site at The

Retreat, while extending, developing and increasing the individual

elements. Its patients were mostly wealthy, members of the gentry and

nobility, but it took some paupers.

The influence of Fox and

Brislington House extended widely in England and Scotland and was

influential on the erection of the county asylums..

The

text of his (about) 1806

promotional pamphlet for Brislington House was reproduced in full with

Robert Reid's Observations on

the Structure of Hospitals for the Treatment of Lunatics (1809), which was

published together with Reid's

proposed designs for the new

Edinburgh asylum.

Fox's pamphlet was quoted as

being a "valuable authority" in the second edition of William Stark's

Remarks on the Construction of Public Hospitals for

the Cure of Mental Derangement (1810). Here Stark republished his proposals

for the construction of

Glasgow asylum, and expressed his regret at not having known of

Fox's

pamphlet for the first edition in

1807, as "it would have supplied me with much valuable authority respecting

many of the statements

contained in my former Report".

Fox's asylum arrangements continued to be

directly influential for some

years.

On

29.4.1828 Edward Fox petitioned the House of Lords against the

provisions of the Madhouses Bill. Fox gave

extensive evidence to the

1828

House of Lords Select Committee

Inquiry relating to lunatics and asylums. His asylum may

additionally have

been influential because of

the number of influential and wealthy people who visited their relations

when patients there. Even in the

1830s W.A.F. Browne commended favourably in print upon the structure of Dr

Fox's Brislington House

and his therapeutic regime.

By the late 1820s Dr Fox accommodated "all Classes of Society" at

Brislington House, but there were very

few pauper lunatics. Classification was as important as in the early days

of the institution, "Not only are

the Classes of Society kept distinct, but three Classes of each Society are

kept distinct according to the

State of the Disease". There was also division by sex. To effect this

classification, the establishment was

divided into six "houses", with two attendants for each one. One other

house was provided, for paupers,

detached from the main group. In terms of cures effected, in 1826 Fox

received 42 patients, 22 of whom

were cured and nine were under gradual improvement; one was discharged to

another asylum, five died,

and the remainder continued at Brislington. There were on average 90

patients in the asylum.

The building stood at the heart of the site, with an open and informal

forecourt to the front and a block of

rectangular airing courts to the rear, and views from the rear towards the

distant Bath Hills. Its six

separate ward pavilions, referred to by Fox as "houses", comprised three

for males and three for females

flanking a central block.

Initially the patients were classified by social rank, then by severity of

symptoms, rather than by type of

illness. Those of the highest social rank were referred to as "ladies" and

"gentlemen", and were allocated themost prestigious accommodation within

the upper floors of the main central block (divided into two for the

separate sexes). The lower ranks comprised males and females of the second

and third classes who

inhabited the two larger pavilions of the three on either side of the main

block. The various social classes

and sexes were never to meet. The accommodation was graded such that the

central block, where Dr Fox

himself lived, was for the higher class, the central two of the flanking

pavilions were for the second-class

patients, whilst those furthest from the main block were for the third,

lowest class. The smallest of the

three pavilions on either side of the main block was for use as an

infirmary or isolation block.

An unusual management and treatment feature was the manner in which a line

of cells was sited at the far

end of each of the airing courts at the back of the building. These

isolation cells, for the more recalcitrant

patients, were placed well away from the ward pavilions so that those

patients who were quieter and less

disruptive were less disturbed by noisy patients. However, they were still

within call of staff and services

from the main buildings. The main building, cells and courts were enclosed

by a wall and the only entrance

and exit, apart from the doorway to the walled garden behind, was via the

main central door opening onto

the forecourt.

On the front, entrance side of the building lay an informal forecourt with

a grand turning circle. This was

divided from the main house and its individual ward blocks by two outdoor

sunken service passages to

allow communication between the blocks, which also flanked and linked with

the central block. To prevent

escapes these passages were divided from the forecourt and wider estate by

a stone wall 11 feet (3.5m)

high.

Behind the ward pavilions lay the line of six walled airing courts, to

which Fox said, patients had access

"whenever they please". Each of the three social class divisions within

each sex was specifically allocated

one of the courts. Those two for the second class were a few feet broader

than those for the other classes,

and the "gentlemen's" court had direct access to the walled garden behind.

Each court contained lawns,

paths and a central viewing mount to allow the patients views over the

countryside to distant hills. The

provision of these mounts was a novel feature designed by Fox. A border

sloping towards the outer wall of

each court in the form of a ha-ha prevented them from escaping, while

allowing a good view of the

surrounding country.28 In general the courts resembled domestic town

gardens, where the emphasis in each

enclosed space was on combining rural views, if available, with ornamental

and convenient amenities for

recreation. The therapeutic use of airing courts had not been classified to

such a degree before. Neither, it

seems, had their layout been so elaborate or provided with features

allowing the patients to take advantage

of "therapeutic" views. Brislington House, along with The Retreat, was one

of the earliest asylums to

promote the enjoyment of the surrounding setting of the asylum for

therapeutic purposes. It is clear that Dr

Fox, as part of as his aim of curing via moral therapy, constructed these

core elements, building, airing

courts and walled garden, to ensure that those patients whom he considered

required confinement were not

allowed the opportunity to escape.

Beyond the airing courts a bowling green and fives-court were provided, and

other "innocent amusements

for exercise" were allowed, probably largely for the higher social classes

of patients.30 In order to provide

ample recreation and employment facilities, and because Fox did not want

patients to be disturbed, or

incommoded by neighbours complaining of disturbance, the asylum was sited

in 80 acres (32 ha.) outside

Bristol on an isolated tract of former common heathland. The main buildings

stood at the centre of what

amounted to an extensive and purpose-built country house estate with

modifications for use in the

treatment of lunatics (Plate 27, annotated plan of estate, 1902). The

traditional country estate elements,

parkland, pleasure ground, lodges, approach drives, and kitchen garden, all

enclosed by a stone wall, were

supplemented with secure, walled airing courts adjacent to the main

buildings. Additionally, a number of

cottages were erected in picturesque style around the grounds, in a manner

reminiscent of Blaise Hamlet

(c.1810), built nearby on the west side of Bristol to designs by John Nash.

The patients' cottages, scattered

in the park in their own small grounds, were for the most wealthy patients

who could not be accommodated

in the main block in the style to which they were accustomed (for example,

see Plate 24, the Swiss

Cottage, built in 1819). In this way they could live, with their own

retinue if desired, splendidly isolated

from all possible social and medical taint associated with the main asylum

buildings, while benefiting from

the proximity of the expert Dr Fox and his establishment.31

Several passages written by John Perceval concerning his enforced stay as a

patient at Brislington House

in 1831 address the uses to which this early therapeutic landscape was put.

Although Fox was initially

reluctant to give gentlemen activities below their perceived status,

Perceval's narrative indicates that

gentlemen were allowed to work in the gardens and grounds of the House.

Perceval complained that upon

his admission in January 1831 there was little for him to do indoors, apart

from looking out of the window

and reading the newspaper. His mother asked Dr F.C. Fox to let Perceval

work in Fox's garden "this was

indeed beneficial, as it gave me occupation and more privacy". Later on in

the year he was employed with

two other gentlemen and an attendant to do further work, cutting out a

small path in the shrubbery, having

been entrusted with a mattock and spade, although he rejected these when

his voices teased him with

contrary instructions, reverting instead to wheeling the barrow, picking up

sticks and using a bill-hook.

Perceval refers to the use of the airing courts, or yards, for exercise and

a change of scenery, as a common

activity for patients, used together with walks further afield within and

outside the grounds. Seats were

provided, and patients might be left on their own, "When left alone in the

yard, [a patient] amused himself

with picking up stones, climbing up into a small tree and sitting there

looking over the country, and one

day he picked nearly all the leaves off this tree".33 Later on in the

1870s, the Reverend Francis Kilvert

recounted in his diary visiting his aunt Emma who was to be found sitting

in the gardens, doing some work

with a cat or two on her lap, where they walked whilst talking.34

Perceval describes a precipitous pleasure ground known as The Battery,

situated on a terrace above the

River Avon, to which the patients were often taken, and its drawbacks for

those experiencing hallucinatory

voices. "At one elevated spot that commanded a view down the valley, a

natural or artificial precipice

yawned in the red soil, crowned with a small parapet, in rear of which was

a small terrace and summer

house [the Battery]". The view was, apparently, enchanting. A photograph

shows the picturesque

summerhouse at the turn of the century.35 Here Perceval sat on the parapet,

overlooking the precipice, "My

voices commanded me to throw myself over, that I should be immediately in

heavenly places" and having

managed to resist this injunction, on subsequent visits he refused to go up

to the parapet, but instead sat in

the summerhouse "to avoid the temptation". Other patients sat on the

Battery, but Perceval disapproved of

them being taken there at all for safety reasons.

The asylum continued to be owned and run by the family until c.1950, when

the asylum building was sold

to the NHS as a nurses' home. Following a period as a nursing home in the

1990s it has been converted

into private apartments, and a school built in part of the park.

The first publicly funded county asylum to open under the 1808 Lunatics

Act. Laid out before

patients were widely considered

to benefit from a regime of exercise, recreation and employment. The two

subsequent asylums constructed under the 1808 Act

(Bedford, 1810-1812 and

Norwich 1811-1814) had buildings and estates largely arranged in

a similar fashion.

In 1808 just under five acres (2 ha.) of land were purchased at Sneinton on

the south-east edge of

Nottingham. The asylum was set at the edge of a rapidly expanding urban

area

and took patients from both

rural and industrial areas. It was constructed initially as a relatively

large establishment for 60 patients.

In 1809,

Nottingham Magistrates sought advice from Dr Fox of

Brislington House about the the asylum and the layout of the asylum

grounds. They were

principally interested in his novel building layout of divisions into

separate blocks (which they did not

ultimately act upon), presumably because they were interested in systems of

classification. Fox also

advised on other matters including the grounds immediately surrounding the

asylum building.

(One of the

magistrates who contacted Fox was the Rev John Becher of

Southwell). (Nottinghamshire RO,

SO/HO/1/1, Nottingham asylum, Committee minutes, entries for March and

April 1809)

It was stated in the 1814 Annual Report that from the outset a "liberal

spirit" suffused the intentions of the

asylum governors, such that by their Fourth Annual Report of 1818 they

could state that, "they have seen

that the system adopted in your Asylum is invariably that of tenderness and

gentleness, united with a firm

and powerful resistance against maniacal paroxysms, yet restraining and

coercing the unhappy patient no

longer than the occasion may require". The liberal spirit was obviously

tempered with a perceived need

for practical restraint at times.

The 1818 Annual Report also related the purchase in the previous year, and

at the considerable expense of

£700, of a parcel of land behind (that is, to the east of) the

asylum. There were three reasons given for this

acquisition, which was considered to be of considerable importance to the

welfare of the asylum. The steep

slope of the land down from the east allowed passers-by to overlook the

asylum and its airing courts,

causing "very great annoyance, which was too frequently found to harass and

disturb the minds of the

Patients placed in those Courts for air and exercise, and to retard their

recovery". The new parcel of land

created a visual barrier to the inquisitive who had no business looking

into the asylum grounds. The second

reason given for the acquisition of this land was that, "it is obvious,

that more extensive means of

employment will thus be furnished for such of the male patients, to whom

bodily labour may be deemed

serviceable". This is a very early example of the managers of an asylum

declaring the therapeutic benefits

of employment. It appears that the employment of patients had already been

contemplated and possibly

carried out, and the original extent of land not found to be great enough

to allow all those to work who

wished to or were able. The final reason for acquiring the land was that

"in the cultivation of this ground,

considerable benefit will be derived to the Asylum". This probably referred

to its economic use to provide

fruit and vegetables for the institution.

Richard Ingleman designed

a building which followed the general plan form of the

Moorfields Bethlem, with men and

women's wings flanking the

central administration and service block. The asylum

was built as one long, three-storey block, with galleries overlooking the

airing courts to the rear. The

asylum was set 300 feet (92 m) back from the road. The building and airing

courts were set within a

tightly drawn walled enclosure (248 feet x 348 feet; 76 x 107m), behind an

area of informal lawn which

was obscured from the road by a screen of trees (see Plate 30, annotated

plan of the estate, based on the

OS 25" plan, pub. 1883).95 A lodge, costing £390, was erected at the

same time as the tree screen was

planted in 1809, even before the committee could afford to put up the

hospital building.96

From the lodge a serpentine drive was cut through the hillside, crossing

the lawn to the turning circle in

front of the asylum building. Dr Fox in 1809 advised that the approach to

the asylum should prevent

patients from seeing the asylum, from seeing visitors to the asylum, and

from being able to guess its

purpose. The asylum did not have a farm attached, but the lawn at the

front, encircled by woody planting

in the manner of an informal pleasure ground, may have been used for

supervised patient recreation.

Fox advised that instead of the three airing courts per side, which his

establishment had, probably only two

airing courts each for the male and female sides were required, one

designated for the "filthy and

refractory", and the other for the "temperate cleanly and convalescent

patients". The building and courts he

recommended should face somewhere between the east and south-west, the

whole being arranged so as to

prevent communication between the sexes by speech or otherwise. Three

airing courts per side were

subsequently built, with a gap between the two central ones to provide

access from the central

administration block to the kitchen gardens beyond.99 The airing courts on

male and female sides each

seem to have been assigned to a different medical class of patient.

In 1828 Halliday referred to the asylum. He expressed his dissatisfaction

with the amount and use of space

for patients to be employed within. He believed that there was 4.5 acres

(c.1.8 ha.) of land attached to the

building, which could take 80 patients. "The land is laid out as a garden,

the cultivation of which is the only

employment the patients have. Their treatment however, seems to be well

conducted, and the strictest

economy preserved, as the expense of each person does not exceed

7s./week".

Some time after 1844 the building was extended, and the airing courts, of

which there were now seven,

were remodelled and thrown into two large main courts, with a third

alongside to the south. The courts

were terraced to accommodate the steep slope up to the east and laid out

with lawns and paths. The land

beyond the courts was laid out as an elaborate terraced garden with wooded

zig-zag paths connecting the

main terraces at the top and bottom. Seating areas were provided at the

back of the upper terrace,

overlooking the asylum grounds below, and a fountain at the centre of the

lower terrace. The setting

became more built up, with networks of streets with small houses to the

west and south, although open

ground remained to the north, and to the east lay large areas of detached

town garden plots and other open

ground.

In the early 1900s the asylum was superseded by the new asylum at

Saxondale, and was closed and

demolished. The grounds were reused as King Edward Park.

One of the

magistrates who contacted Fox was the Revd. John Becher of Southwell).

Becher was active in other

schemes of social provision and classification, for in 1808 a workhouse had

been erected in Southwell to

his design, for 84 pauper residents of the parish, which was, as he

maintained, "constructed and governed

upon a principle of Inspection, Classification, and Seclusion".92 Becher

piloted and also helped to design its

even larger and more influential successor at nearby Thurgarton in 1824

(discussed in more detail in Chapter 4 of Sarah's thesis).

Norwich asylum was built three miles or so (5km) east of the city at

Thorpe. The individual airing courts

were laid out with gravel paths and grass plats, and were enclosed by 13-

foot (4m) high brick walls which

had to be raised once the first patient had escaped over them in 1814. As

with Nottingham, the two central

courts were divided by a narrow passage, this time flanked by an arcade

leading to the hospital buildings

for men and women respectively, each with its own small airing court. The

asylum was approached via a

walled forecourt with railings flanking gates leading straight off the

Yarmouth turnpike road which lay

close by. The remainder of the grounds were given over to a cemetery,

kitchen garden and drying ground.

The cemetery was laid out in 1815 at the south-east corner of the airing

courts, enclosed by a four and a

half-foot (1.5 m) high wall and consecrated by the Bishop of Norwich on 4

August 1815.

A lengthy description of the asylum in 1825 presents a very positive

account of the establishment and its

management. The writer described the situation as being "on a fine, open

healthy spot, near the Yarmouth

Road", approached via four iron gates set into cast-iron palisades on low

brick walls which gave access to

the "fine, open yard" in front of the building. He writes approvingly about

the arrangements for the patients

within the building. The airing grounds were reached directly by the

patients via their day rooms and

galleries on the ground floor, each wing (one for each sex) having three

areas, which the writer classified

as an airing ground, a probation yard, and a convalescent yard. The

description does not mention how the

patients were classified within the accommodation in the building itself,

although the men occupied the

west wing and the women the east. Each yard was enclosed by walls high

enough to "insure the safety of

the patients during the hours of recreation", and laid out with grass

panels intersected by gravel walks

which gave them a "neat and pleasant appearance". The male and female yards

were separated by a

semicircular courtyard, as shown on Stone's 1816 plan, from which a passage

led south to the other

offices. The court contained an arcade which continued along the passage,

leading on the west side to the

men's hospital, the nurses' room, a drying room and a stoving room. A yard

was appropriated for the use of

the hospital patients. On the east side of the passage was a similar

arrangement for women, with the yard

being used by convalescents. The author also mentioned the remaining part

of the site being appropriated

for a "burying ground", spacious kitchen garden, coach house, stables and

other offices.

In the early years of the asylum little written reference has been located

to the patients using spaces

outdoors anywhere other than the airing courts. Halliday's brief

description of 1828, as part of his countrywide

survey of asylums, referred critically to the asylum in terms of the amount

of space for patients to be

employed within. "It has not the advantages to be derived from a farm or

great extent of garden, but upon

the whole, is a well-arranged and ably conducted establishment".

The original five-acre (2 ha.) site was not greatly extended until the

1840s, after the Metropolitan

Commissioners in Lunacy had complained in 1843 about the seats and benches

in the airing courts being

furnished with chains and leg locks, and the inadequate extent of land

which they viewed as so essential to

the occupation of the patients.83 By January 1846 the Commissioners

reported that a considerable number

of men were employed in the yards and outhouses and the grounds and

gardens. Two and a half acres (1

ha.) of land was bought in 1847, providing a total of seven and three

quarter acres (3 ha.) for the use of the

patients, the new land being laid out partly as a garden and partly as a

pleasure ground intended for the

women patients to enjoy air and exercise

The building was extended by the county surveyor, John Brown c.1849 and the

male and female sides were

reversed to east and west respectively. The original arrangement of six

airing courts was remodelled to

form two large airing courts, one on each side of the south front, with two

new courts to the west and east

of the building. At that time a large, square kitchen garden lay

immediately to the west of the main

building, with a further area of kitchen garden to the east, and to the

north of this an area labelled "garden"

containing what appears to be an orangery or similar structure. The

cemetery, the narrow Governors'

Garden, the Drying Ground and Bowling Green formed a narrow band of open

land which separated the

hospital from land running down to the river to the south.85 At the same

time or shortly after, the turnpike

road was moved further away to the north to allow more room for expansion

and create more privacy from

the public road. Because of this the main entrance and lodge were

demolished and new lodges were built.

Following the re-routing of the road in a cutting, in 1856 a new and

substantial bridge, also by Brown, was

erected across the road, allowing male patients unhindered access from

their accommodation on the east

side of the site to the farmland to the north of the road.86

By 1854 there were 298 patients, and a further 30 acres (12 ha.) of land

had recently been bought, in

response to further criticism by the Commissioners in Lunacy and their

recommendation that this

constituted the minimum amount required for an asylum containing up to 300

patients. It was hoped that

the general increase in the space available to patients would lead to a

lessening in the number of chronic

patients and the lessening of the mortality of the other patients. The

exact use of the land had yet to be

decided, whether the more general activities of farming would be carried

out in addition to "spade

husbandry". It was believed that, "The more varied and extensive the

occupation of the patients, the more

fully will be developed their individual capabilities".87

The 1854 report admitted that the limited amount of asylum estate land had

until then made it difficult to

find work for those patients used to agricultural work. Idleness was

regarded as a major limiting factor to

the recovery of the patients. In the summer a piece of land had been rented

and 50 men were engaged daily

in "cricketing" and after that a large number were employed on the land;

however, nearly all the patients had

some kind of physical ailment, restricting the amount of work they could be

expected to undertake.

Marching drill occurred in the grounds, as "Great control is gained over

the patients, and the task of taking

a vast number to a distance from the Asylum for air and exercise, becomes

comparatively easy".

A self-contained annexe for 280 "quiet" cases of each sex was built c.1878-

80 at some distance to the north

of the original complex, on 24 acres (10 ha.) of land bought for the

purpose. This New Asylum stood

remotely in a large expanse of agricultural land and was provided with

airing courts which were enclosed

by sunken fences. The old and new complexes were connected by a sunken

drive across farmland which

left the turnpike road opposite the lodges. The old path which had

connected the two sides of the site since

the 1850s, carried by the bridge across the turnpike road, had been planted

up as an avenue. At the south

end of the path, in 1891-1892, the superintendent's house was built, set in

its own spacious grounds to the

east of the path. In 1899 all the male patients were moved to the New

Asylum and all the female patients to

the Old Asylum. In 1900 13 acres (5.25 ha.) were bought, and the New Asylum

extended for a further 150

patients. The southern, earliest part of the asylum closed in the late

twentieth century, and the building was

converted into apartments.

The Wakefield asylum was the earliest public asylum to introduce the use of

work in the building and

grounds at a significant level as a form of therapy, reflecting the

increasing interest in moral therapy in

public asylums. As such it was influential on other public asylums. Its

first medical superintendent,

William (later Sir William) Ellis implemented this programme, the asylum

having been constructed on an

expansive site with advice from Samuel Tuke of The Retreat, York, where

work was already a major

element of treatment. Tuke expressed his opinions on the laying out of the

asylum structure in print, and

the plans for the asylum were also published.

The Retreat - The landscape

"These creatures are generally very familiar with the patients: and it is

believed they are not only the means

of innocent pleasure; but that the intercourse with them, sometimes tends

to awaken the social and

benevolent feelings."

Brislington House - The Landscape

Nottingham - The landscape

Elements of the grounds

beyond the airing courts were

used for patient recreation, and from about 1818 for employment for those

patients who were considered to be

in an appropriate condition to use them.

Southwell workhouses

1808-1836: Southwell Parish Workhouse

1824 to present: Thurgarton Hundred Workhouse, which

became Southwell Union Workhouse in 1836 (Now a museum)

Southwell workhouse open to the public

See Peter Higginbotham's site

PAPHE website

Norwich - The landscape

Wakefield - The

landscape

Hanwell - The landscape

|

|

Study

links outside this site

Study

links outside this site

Picture introduction to this site

Picture introduction to this site

Andrew Roberts' web Study Guide

Andrew Roberts' web Study Guide

Top of

Page

Top of

Page

Take a Break - Read a Poem

Take a Break - Read a Poem

Click coloured words to go where you want

Click coloured words to go where you want

Andrew Roberts likes to hear from users:

To contact him, please

use the Communication

Form

asylums index

Bethlem:

Brislington House:

Conolly 1847:

Corridor: -

Corridor-

Pavilion -

criminal lunatics

Derby:

Echelon: -

Broad Arrow -

CompactArrow -

Later Type

Ewell:

Landscapes

France (Ivry, Charenton, Rouen,

Vanves)

Hanwell:

Jacobi 1841

asylum situations

-

arrangement of departments

-

licensed houses

Middlesbrough:

Landscapes

Norfolk:

early - developed into corridor plan -

Landscapes

Nottingham:

early - developed into corridor plan -

Landscapes

Pavilion:

Corridor -

Standard -

Dual -

Radial -

Irregular -

Echelon

Retreat:

Landscapes

Wakefield:

Bishopsgate:

Moorfields:

original airing courts

1730s airing courts

St Georges

Jacobi form -

functions -

early colony plan? -

Landscapes

one of models -

ideal

features -

table -

functions -

Landscapes

Jacobi form -

Corridor plan -

functions -

Landscapes

forms -

model used?

Jacobi form -

developed into corridor plan -

functions -

Landscapes