Cosy Corners in Depression and War

Autobiography of

Joan Hughes

The story of one person's nests

1985

The months of January and February seemed quite dismal. I was not doing an Open University Course this year, because I felt that I would need most of my time to attend to business at Manningtree, where my father's house was now standing empty. I was being pressed to find employment by the Department of Employment, but there was nothing available. My chest was very weak. Eventually I obtained a clerical job but had to leave after two weeks owing to the fact that I had to sit next to a smoker, and this was liable to aggravate my chest trouble. Luckily the employer was good enough to declare me unsuitable for the post when I left, after I had explained the situation. This meant that I could continue to receive social security payments without questions being asked.

I was worried because I did not feel well enough to visit my father in Dovercourt while the weather was cold, and resolved to visit as soon as Spring arrived. About April I made a visit and found my father getting on fairly well. I visited the office to talk to the manager of the nursing home and he said "He's has made a good relationship with Doris", naming one of the nursing assistants. Doris was standing in the corner of the room and said that she got on very well with my father.

I looked out and found Dad walking along the corridor to the office. He wanted to know what I was doing and what I was talking about. I was pleased to see that he was able to walk and climb the stairs to his room on the first floor. He had given up smoking at last. He had breathing troubles and had sensibly decided not to smoke at the age of 87.

I was being urged to sell the house but my father did not want to sell it. I felt unable to live there, as there was no central heating, to which I had become accustomed in London, and that winter was exceptionally cold. My heating bills in London were exceptionally high. Often I would wake in the night and have to get out of bed and sit upright, with the gas fire turned on. I had choking sensations and my throat became filled with phlegm. I was able to bring up some of this with the help of cough mixture. The doctor gave me anti-biotics from time to time, as I often had sudden temperature rises and acute bronchitis. The anti-biotics alleviated my symptoms but produced no lasting cure. I noticed that I was exceedingly weak and often could not manage to bolt and unbolt a door, and do other very small jobs, which was very embarrassing in public situations. The doctor told me I was very debilitated but did not suggest any treatment. I lost faith in this doctor. Andrew had told me to change to the practise in Lower Clapton. I made my change of address an excuse to change. In Spring I visited the new doctor and he gave me a series of tests and sent me for an X-ray which proved that there was nothing organically wrong with my chest. However the attacks of what seemed like a mild form of asthma were continuing. So the doctor prescribed a broncho-dilator; a teaspoon to be taken when I felt short of breath.

I felt that I had only just survived the winter even in a warm flat with the central heating turned full on. In the worst weather I left the heating on all night, as when I went to bed I was often in pain, and suffering many attacks of breathlessness. Even though I was short of money I felt it necessary to spend what I had on heating and thought that if I had had to live in the house in Manningtree, I would not have survived the winter.

When slightly better I determined to improve my fitness to tackle small jobs and purchased a book which gave details of exercises to be performed for twenty minutes three times per week. Throughout most of the winter I carried out these exercises and began to feel stronger. I felt they had been as much benefit to me as the doctor's ministrations. But the new doctor was decidedly better than the old one. He was much more conscientious.

By April I was somewhat better and stayed a few nights in the house in Manningtree. I was glad to leave as my chest trouble showed signs of coming back.

Probably my father was right about not selling the house but I felt I had to sell it. The pension my father was receiving was enough to cover nursing home expenses so there was no urgency to sell. I was nervous about leaving the house unattended.

There was a person anxious to buy the house, living not far away and I was subjected to visits from her and pressure put upon me, whenever I visited Manningtree. Her boy-friend called and offered an exceptionally low price. For this reason I put the house with an estate agent. The price I was offered was £24,000. This neighbour got angry as if I had done something wrong, but so far I had not accepted her offer. I told her that I had been offered £24,000 by a buyer from the estate agent, and she raised her offer to this level. I agreed to sell but the contracts were not ready to sign. My father refused to sign them, saying the price was not high enough, and that I should receive at least £30,000. But this sort of offer was not available. The house was not insured, as my father had discontinued paying insurance two years ago. The contents were not valuable, but I was worried lest the house catch fire or suffer other calamity while vacant. Not being the owner I was unable to take out an insurance on it, and as a social security recipient, would have been hard put to be able to afford it. These things worried me. The advice I received from relations was hardly helpful. Leonard was urging me to sell, saying the money was needed to pay nursing home fees in the future. I did not think he would listen to any explanations from me, so did not explain the situation fully to him. Neighbours in Manningtree and some of their friends were all anxious that the particular person who had already offered to buy Dad's house, should be successful in this and get to live in the house. The next-door neighbour to my father was a close friend of hers. Meanwhile whenever I stayed in the house, there were signs of my chest trouble returning so I could never stay there very long. The house was very dusty, and as my father had been a heavy smoker, the residues from this were probably still lurking around.

Once when I was in bed in the upstairs front room, I felt I was choking. Then I thought I heard my mother's voice. She had died in this house, in the next room, 37 years ago. "Open the window, Joan," said a voice in my mind. At about 2 am that night, I got out of bed and opened the window. Relief came immediately as the fresh air flowed in. I went to sleep until 9 am, got up and started business. The next job was to cancel my father's television rental and ask for the set to be collected. It was an old black and white set. As soon as it was taken away, I missed it, as I had been watching it on lonely evenings. However I did not expect to be visiting the house much more, as I expected it would shortly be sold.

|

I gave Leonard a spare set of keys to the house and asked him to visit and collect his pictures. There had always been a dispute in the family about these pictures. I did not want them and was glad for Leonard to have them.

They had been painted by Leonard's father and grandfather. The best ones were by his grandfather and were of Royal Academy standard. Perhaps they could be sold for up to £500 each but not more. They were not exceptionally valuable. Aunt Violet, Leonard's mother possessed them in 1940 in a flat in London. She abandoned this flat leaving them all behind and fled from the blitz in London.

After getting Aunt Violet into a hospital, my father visited this flat in London. He saw these pictures painted by her husband and father-in-law and took them out of the flat to store at the house "Gordona" in Manningtree which was then the residence of my mother's mother, no relation whatsoever to the Nobles. However if he had not done this the pictures would have been lost. Aunt Violet had abandoned all her possessions and the flat in London. This is my father's side of the story and was the version which I believed. Aunt Violet had to spend 6 months in a hospital in 1940 and was unable to return to that flat in London. I am inclined to believe the pictures would have been lost if my father had not taken them. Leonard was a child evacuated to Devon at this time.

Aunt Violet's version of the story was that my father unlawfully removed the pictures from her flat. They were her pictures and my father had taken them away from her. This was the version of the story which Leonard believed. The pictures were never put on the walls at "Gordona" until my grandmother died and my mother took over the house in 1942. They remained on the wall for over 40 years. Aunt Violet could have collected them but never had the energy or transport. Neither did Dad have the energy to bring them to her flat in London. However periodically Leonard got very cross that he did not have these pictures in his house at Romford. It was no good telling me off about it, I thought, because I could not have done anything about these pictures.

Leonard eventually said that he was content for Dad to keep the pictures until he died or left the house, "Gordona". I had no wish to keep these pictures but could not persuade Leonard of this. It was a most unfortunate and unnecessary dispute.

I was glad to hear that Leonard and Teresa in their car had visited "Gordona" and brought these pictures back to London at last, and that I would not be hearing any more about them. There was more work at "Gordona" than I could physically accomplish. This was the reason for some of my poor decisions about letting most of the contents go. I waited until I was sure that Leonard had collected what he wanted and visited the house again to sell the contents. Unfortunately someone had torn wires away from the wall and I could no longer get even a wireless to work at "Gordona" when I visited. Luckily the electric fire in the sitting-room still worked. I spent a very miserable time at "Gordona" when I visited in May and again in June. I visited my father in the nursing home in Dovercourt. Again he had refused to sign the consent form to sell the house. A solicitor living in Dovercourt was visiting him. This shows a lot for his strong will even when quite ill.

During the course of this summer I often felt very depressed, and felt I had much reason for it.

In August I finally sold the contents of the house and by this time the sale of "Gordona" was ready to go through. Dad had finally signed the consent form. I only received £300 for the contents of the house. It was a very poor deal. I had had a new washing machine owned and paid for by me fitted in the house. I told the dealer not to take this, but he ignored what I said about owning it myself and took it. This is the sort of thing I should have disputed as I lost money on this deal, but I felt too weak physically to dispute this. I had no energy even to see the dealer in his shop in Mistley.

In September I stayed at a guest-house in Dovercourt. This gave me a little holiday and enabled me to visit my father easily. I had found day trips from London very tiring.

I went to visit again on October 1st on a day trip from London. I walked along the beach in the morning and picked up a few whelk shells. Dad found it hard to talk and I thought it might form a subject for conversation if I showed him the shells, carefully washed in the ladies' lavatory. I bought four kiwi fruits as a present. The last time I saw Dad at "Gordona" he asked me to buy him some kiwi fruits, which were still rather expensive to buy as in 1985 they were only just beginning to be imported from New Zealand. Unfortunately until now I had never had the opportunity to take him any kiwi fruits and thought he would be pleased with them.

When I saw him he was in his private room. He was very pleased with my copy of the "Guardian". He seemed quite well but said he was no longer well enough to sit in the day-room. There was a jug of water on his bedside table, as he needed to drink quite often. I felt confident that the staff were looking after him very well, but realised that he might die soon. He asked if the kiwi fruit were sweet and I assured him that they were sweet. He seemed puzzled when I showed him the shells from the beach and asked me what I was going to do with them. Two of these shells remain on my window- sill to-day, together with a polished pebble taken from the Isle of Iona by a friend. They are simply sentimental objects, not fussy and not taking up much room. Space is limited in this small flat. I think they are attractive, though not exceptionally beautiful.

Dad thought the government should be thrown out. I was glad he was cheerful enough to talk about the government in his old way. He concealed the "Guardian" newspaper beneath the cushion of his arm-chair, explaining that everything was taken out of the room when the cleaners came. He thought this "Guardian" would provide him with enough reading matter for a week.

He thanked me for visiting but asked me not to come for another month. He said he wanted to be quiet and did not want to see any other relations. I respected his wishes and decided to visit again at the beginning of November, but two weeks later I was in bed in the flat in Saratoga Road. It was about October 13th. I heard my father's voice quite distinctly. "It time you came to see me, Joan," it said.

Next day was the 14th October and I caught the train to Dovercourt. Luckily the weather was fine and I was feeling quite well, the chest trouble having abated. I was able to make the journey quite easily and bought some more kiwi fruits for Dad, arriving in the afternoon.

When I arrived he was having afternoon tea in the day-room. He was pleased to see me but said that it was too soon for me to visit him again. "You said you would not come until the beginning of November," he said. He asked again if the kiwi fruits were sweet. I put them in a paper bag and labelled them "Mr. Martin" and gave them to one of the attendants, because he did not seem inclined to pick them up. I was pleased to see that he had eaten some cake that afternoon.

He was talking quite volubly hoping that I had enjoyed the journey, going out for the day to Dovercourt. I stayed for about an hour. When I got up to go he said "Good-bye." He called back as I was leaving and said "I want to say good-bye." He did this two or three times and I kept going back, and saying good-bye again. This was unusual behaviour, because usually he said good-bye quite matter-of-factly.

Eventually I said "Good-bye. I have to go now", and the last thing that I can remember was Dad calling after me, saying "Good-bye" in quite a loud voice.

"He can't be too ill, if he can talk as loudly as that," I thought, but I was wrong. That was the last time I saw Dad.

|

16.12.1985 Letter Joan Hughes sent to the New Scientist

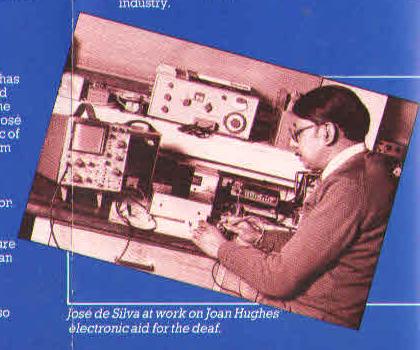

I have noticed ... several references to 'aids for the deaf' consisting of a transmitter coupled with a receiver worn by the deaf person... This idea ... is not the specific invention of John Walker, electronics engineer of Cambridge. A doorbell device for the deaf with the identically similar electronics to that attributed to Walker was suggested by my father, John Martin, in 1982. This would enable deaf people to 'hear' the doorbell or telephone. As I had had a scientific training, I drew circuit diagrams for his idea, slightly modified by my more recent study of electronics, and filed a provisional patent on February 7th, 1983 (8303288). The technology was probably not novel, as the Patent Office pointed out, but this was claimed as a new use for it. I attempted to develop the project at home, but soon realised that the expenses I was occurring were unjustified. For example, electronics catalogues did not state whether or not a licence was required for the small transmitters before sale. So I turned the idea over to the London Innovation Network who are now developing it. |

|

|

|

Index