Cosy Corners in Depression and War

Autobiography of

Joan Hughes

The story of one person's nests

THE STREET

The Street I lived in was called May Street. May is also my second name. I was never sure whether I was called May after the street, after my mother's sister, Agnes May, known as Aunt May, or whether I just took my father's name. He was oddly named John May Martin; he told me May was an old family name.

May Street was where I often played. The main games were marbles,

unhealthily played in the gutter; or skipping endlessly; or a complicated

ball-game, which could be played with others or alone. The ball-game

consisted in a series of pitches against a wall, but there were ten

variations on how the ball was thrown, which had to be executed in the

correct order, otherwise one was "out". The child who first completed the

sequence was the winner.

These games were usually played with other girls living in the street.

At one end of the road next to the corner shops lived Jean. She was a

silent child, but invited me into her front garden sometimes, where there

was a beautiful Virginia creeper.

Much more talkative was Lois, three years younger than me. Unlike me,

she liked dolls and had a magnificent pram. But she also liked colouring

drawing-books and other such quiet occupations. Her parents were very

devout members of some nonconformist church. Part of the rule was that Lois

was not allowed to play with toys on Sundays. Nevertheless, I often saw her

on Sunday afternoons, and she had her colouring books out in the front

garden.

"Lois, you told me that you were not allowed toys on Sundays. " I told

her.

She said, "Ah, but these are religious drawing books, containing

pictures of Jesus and bible illustrations." I looked at them and thought,

"Well they are nice colouring books, so the religion can't be so bad."

She told me that Lois was a Bible name. Her big brother, about two

years older than me was called David. She said all her church members had

bible names. There was another family of four, also of the same faith. The

girl nearest my age was Jessie, who I included in play sometimes. Her older

brother was Joseph, and younger sisters Ruth and Faith. I disputed whether

all these names were from the bible, but Lois won the argument, saying that

"Faith" was on every page of the Bible. I had to agree, as I had very

little biblical knowledge.

An adult I met sometimes in the street was "Uncle John", who took

little notice of me, but I stopped him always to ask if he had any

cigarette cards for me. He would usually oblige. We did not often invite

any friends into the house, but the children were allowed into the small

front gardens and occasionally into the back gardens.

The reason my mother did not invite any one in was because we always

had a full house. We took in lodgers, one with an upstairs room, and one

downstairs.

My mother's name was Gladys. She had a friend living at the other end

of the street. She was also called Gladys and ran a clothes catalogue. My

mother bought clothes for herself and occasionally for me on the instalment

system. This was called a clothes club and I had to take the money weekly

to Gladys, when my mother did not feel like doing it herself. But I think

Gladys was one of the few friends my mother invited in occasionally.

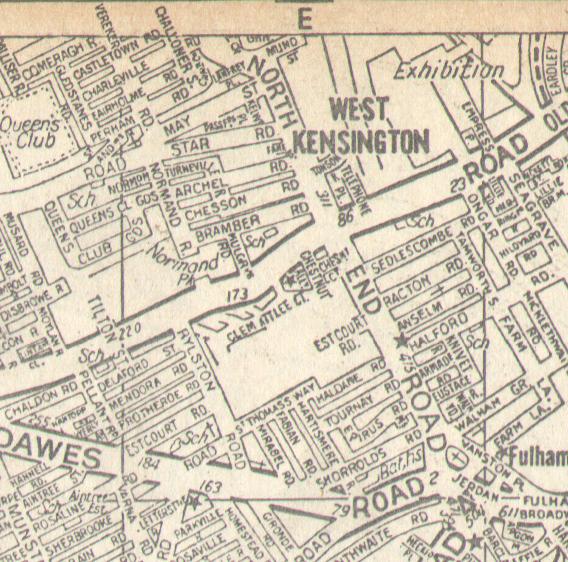

As soon as I was old enough, from age seven I think, my parents sent me

on errands to the shops at each end of the street. In those days there were

no supermarkets, but once a week my mother did her shopping in North End

Road, on market day when this road was filled with stalls selling fruit and

vegetables, much like to-day. The medium-sized grocers, Gapps Stores for

tea, Sainsbury's for other groceries, the new "cut-price" shop,

occasionally a small butcher selling rabbits and stewing steak were the

shops my mother regularly visited.

But I got small items for her during the week. There was Wilson's, a

small grocer's near St. Andrew's Church, which I passed every day on my way

to school in Greyhound Road. Here I would buy sugar, butter or tea

occasionally when my mother had run out. Opposite Wilson's was Cosy Corner,

a sweet-shop primarily, which also sold cigarettes. Here I was given

twopence for chocolate on Saturday mornings, when I would also usually

purchase twenty "Weights" cigarettes for Dad. In those days it was legal

for small children to buy cigarettes, but not smoke them of course.

In the week, I might have a farthing "everlasting stick" made of

toffee. For a real treat, I would also have a "Wall's" water-ice wrapped in

blue-check thin cardboard. These could be sawed in half, and often when I

had not the money for a whole one, I would offer the ice-cream man a

halfpenny and wait patiently while it was sawed in half.

Though I would never have dreamed of trying to smoke one of my father's

cigarettes which I had brought from the shop, I was often afraid of doing

quite reasonable things, or so it seems, as my father even complained about

me rustling paper during his afternoon rest on Sundays. Fortunately, he was

out much of the time at week-ends, always on Saturday afternoon, when I was

told he gave "political speeches" drawing a crowd by jumping up on a

soap-box. He was a powerful speaker, very persuasive, and my cousin has

often said "Uncle Jack could have sold refrigerators to Eskimos!"

When I was not buying cigs for Dad, I was buying a loaf of bread for

Mum. Hemmings the baker's was at the other end of the street on the same

side as Cosy Corner. Here I often bought a crusty loaf, always white bread

in those days. I don't think wholemeal was available in our local shops, as

we had never heard of "healthy eating". Nevertheless the food my mother

provided was very varied, even when money was short Hemmings issued a

ticket with every purchase, recording the amount spent. When we had

collected about one pounds worth, we were entitled to a free box of cakes,

costing one shilling. I used to hang about outside Hemmings, as many

customers dropped their receipts, and would pick these up, so that every

two months, I had gathered enough to get this free box of cakes, twelve in

a box, and I preferred them to my mother's home-made cake, in that strange

way of children. Mum's home-made cake was usually in two parts, baked as

one cake, one side contained caraway seeds, the other currants and

sultanas. The caraway side was for Dad; he preferred this.

Opposite Hemming's was a public house, the only building left still

standing today from the old May Street, which was demolished, around the

mid-seventies to construct a block of flats in the form of an estate. The

pub was called "The Clarence". Every Sunday I would call at the side

entrance, an "off-licence" section, for a pint bottle of Watneys' Indian

pale ale.

I set off for the off-licence one Sunday morning to buy a pint of ale

to go with Sunday dinner and was proudly bearing it home, when for some

reason I had to cross the road. As always, when the coast was clear, I

almost run across. This habit was acquired because my father was always

shouting "Hurry across the road." He meant "Be careful!" Yes, I did look

each way, up to three times before crossing. In the middle of the road, I

dropped the bottle of ale, which broke into many fragments. Not a drop of

drink was left. Only the stopper remained whole. I sat down in the middle

of the road and cried, fearing my father's ire, and for a few moments,

careless of the traffic. But perhaps I did stumble to the road side to

continue crying. A middle-aged man crossed over to see what was the matter

with me. I had never been told not to talk to strangers, at least not in

our street, so I told him, that my father would be very cross, and I was

afraid to go home now. He said, "Don't worry, Have you got the stopper?". I

picked it up.

He said "The Public House will replace the bottle, if you go straight

back and tell them you have dropped the bottle, and show the stopper."

This cheered me up, and I thanked this kind stranger, but only half

believed him. But I went back to the off-licence and they did replace the

bottle of beer. I thanked them profusely. The stranger had told me this was

the usual policy . But I'm not sure about that. All I know is that they

probably recognised me, and whether it was their usual policy or not, they

replaced the bottle of Indian pale ale. When I got home, I said "Here's the

beer, Dad"; that was all I said. I did not tell my father of this incident.

I remembered this man for long afterwards but did not see him again.

Neither did I ever drop another bottle of beer in the street. I was very,

very careful.

There is not so much more to relate about the street. On Saturday

mornings, my cousin Leonard would often visit to play with me. He was an

only child also, with no other relations nearby. Aunt Violet, his mother

had been a widow since he had been eighteen months old. One of the games he

liked playing was "car spotting". Probably about 12 to 20 cars per hour

passed by on Saturday mornings. There was no roadside parking. Probably

no-one living in our street owned a car. The shopkeepers may have had small

vans. At that time cars were owned by "the gentry".

The object of the game was to spot the make of car. The usual makes

were Austin and Morris, with occasionally a Bedford van. My cousin told me

this. It was his game and he was better at it than I was. At the end of an

hour he had spotted about 6 Austins and possibly 3 Morris's if he was

lucky. He did not usually miss a car. But I was usually only able to see

the make of two cars, before they had whizzed by. We were both standing

safely on the pavement, and to see the insignia on the front of the cars

was quite difficult. Occasionally there passed a rarer make of car, unknown

to Leonard.

Horses also used the street. There was the coalman, the rag and bone

man, and sometimes someone calling out "Apple a pound pears!" or that was

what it sounded like, but he passed by early on Saturday mornings, before I

had got up. My father saw the horse manure in the middle of the road and

coveted it for his small back garden. He would ask Leonard to scoop it up

for him, but Leonard always refused. I said "I would do it!" but he refused

this offer, saying it was too dirty a job for me. I don't know who cleared

up the horse manure. Street cleaners would work before children came out in

the mornings , so I never saw them. But I did see the lamplighter. There

were gaslamps in the street, one just outside our house, and I would often

watch the lamplighter lighting this lamp on winter evenings, from the

upstairs front window.

Sometimes, an old man would set up a piano at the end of the street

near Cosy Corner. When this happened , I think my mother would say "Keep

away! These are not nice people". This man had a monkey who sat on the

piano, and was accompanied by a woman who danced, wearing fancy dress.

Mother liked animals. She would have considered this treatment of the

monkey unsatisfactory. Aside from this, these people were asking for money,

of which we had little. So usually, I just observed these people from a

distance.

But the street corner bookmaker was a popular figure. The bet was

"Sixpence each way!" and one horse was selected. I would be asked to go up

to this man, when he was out and about on Saturday mornings, and place this

bet. But I was told, "Make sure there isn't a policeman about!" I enjoyed

the frisson of excitement I got from doing this. We were very honest people

in the street on the whole. Back doors could be left open. But somehow, we

were wary of policemen. Perhaps I had been told when very small, "If you

are naughty, a policeman will take you away!"

George V celebrated his silver jubilee in 1935. This was the occasion

of our first street party. A special holiday from school was given, and the

children received Silver Jubilee mugs. In the morning, we took our small

Union Jacks to wave, when the King and Queen passed by, in their

horse-drawn carriage, and to watch the accompanying procession through the

streets in Central London. I'm not sure where my family stood. It was

probably in the Royal Borough of Kensington, near Kensington Gardens; this

being our nearest large park, we knew it well.

I did not appreciate this event. Being seven years old, I could not see

over the heads of the people in front, and got tired of waiting. But while

we had been away the street had been decorated; strings passed high across

the street from upstairs windows on one side to those on the other side.

The men of the street must have got their ladders out while the rest of the

family watched the morning procession. The decorations were mainly

multi-coloured rags cut in strips, with a few prominent Union Jacks. There

were very few commercial paper decorations, the street dwellers could not

afford these. Sitting at trestle tables beneath the gay streamers, the

children had a street party. We wore coloured hats from crackers, as if it

were Christmas. As there were no parked cars, and little traffic in

residential streets, these parties were easy to arrange by the street

dwellers themselves. The women of the street had co-operated to make

jellies and cakes; there was much excitement and jubilation, and as we

drank our tea, we said "God bless the King!"

For days afterwards, my mother took me for walks round nearby streets,

admiring the decorations, which were left up for a week or more. Fane

Street was a narrow alley. May Street people looked down on it, but it too

had marvellous decorations, and we wondered how the people there had

managed it. I voted it the best display. Incidentally, Fane Street has

survived to this day, and is now a gentrified street, unlike demolished May

Street.

|

|

|